[ad_1]

In Myanmar, where nearly half the population remain without basic road access and more than half of the existing highways and railways need repair, improving connectivity through infrastructure is a key challenge. The country ranks 137 out of 160 countries in the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index in 2018, and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has recommended doubling the country’s spending on the transport sector from its current mere 1-1.5% of GDP.

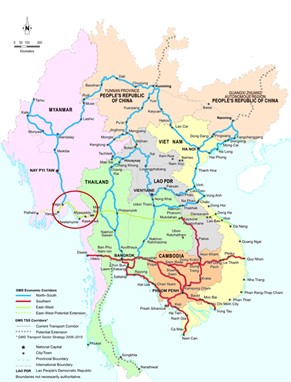

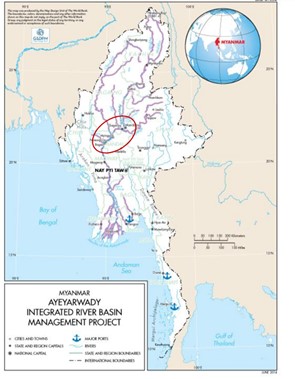

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) such as the World Bank and the ADB have made significant contributions in Myanmar’s effort to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 9 “build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation”. With multiple risks associated with large-scale infrastructure development, the presence of “risk regulators” becomes essential, making MDBs key players to ensure safeguards. Here, we examine the role of MDBs as “risk regulators” through two flagship projects: (i) the World Bank’s river navigation enhancement project along the Ayeyarwady River and (ii) the ADB’s regional connectivity highway construction project in Kayin state (see Map 1). By looking at the MDBs’ safeguarding role in both projects, we show that their performance was patchy, leaving scope for risks to emerge.

Figure 1 (left): Map of Ayeyarwady River Navigation Enhancement Project (World Bank)

Figure 2: Map of GMS Economic Corridor (ADB)

The World Bank and its river navigation enhancement project

The Ayeyarwady is Myanmar’s largest and most important river. According to the World Bank, the basin accounts for over 60 percent of the country’s landmass, accommodates 70 percent of the population, and transports 40 percent of the commerce. Recognizing the importance of inland water transport to economic development, the World Bank provided a $38 million loan for improvement of navigation, to be implemented by the Directorate of Water Resource and Improvement of River Systems (DWIR) within the Ministry of Transport and Communication. Its rationale is to create greater market opportunities and to boost country’s economy through increased connectivity via inland-water transport.

Despite its potential economic benefits, the project generates significant social and environmental risks along the river ecosystem and across the river basin. The project is classified as category “A”, the highest degree of risks based on the World Bank’s Operational Policy. Negative impacts became visible early on, including damage to homes and agricultural land, leading to loss of livelihoods. Local communities lost agricultural land and houses due to increased riverbank erosion at project sites. Improving shipping channels, which involves dredging and shoreline construction for riverbank protection, not only leads to changes in existing patterns of transport and commerce that benefit some communities and bypass others, but it also accelerates the river flow, which intensifies riverbank erosion.

Figure 3: Damaged monastery along the Ayeyarwady River (taken by author on October 9, 2018)

Addressing the social and environmental impacts of this project requires government commitment and capacity to protect livelihoods and the environment in accordance with World Bank and national safeguard policies. However, the damage caused by this project indicates weak safeguard implementation. A local environmental activist said, “public awareness on the project is very weak because of the poor public consultation and engagement with local communities and stakeholders.” The NGO International Financial Institutions (IFI) Watch Myanmar made similar claims, stating that Free Prior Informed Consent was not sought from communities along the river, and that public consultation was limited to two major cities, with poor transparency. Furthermore, the project website provides no specific information on which areas and communities may be affected, and how.

The DWIR is primarily responsible for conducting public consultation, and for ensuring meaningful participation of local communities in the project implementation—and it has clearly failed. As a risk regulator, the World Bank should ensure that the government is following its safeguard policies throughout the project cycle. Effective implementation of safeguard policies requires establishing effective compliance and grievance mechanisms as well as monitoring and evaluation systems. However, evidence suggests that both government and the World Bank fail to effectively implement their own safeguard policies.

The ADB and its Regional Connectivity Highway Project

The ADB’s flagship initiative in Southeast Asia is the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), which aims to improve regional connectivity and infrastructure regulation, among other things. For example, through the GMS’ Core Environment Program (CEP), the ADB provides technical and legal expertise to the Environmental Conservation Department in the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation (MONREC), on infrastructure safeguards and environmental impact assessments (EIA). A prominent component of the GMS’ agenda in Myanmar is the regional connectivity highway project. Led by the Ministry of Construction (MoC) with loans from the ADB, this involves two road projects: the GMS East–West Economic Corridor Eindu to Kawkareik Road Improvement Project (GMS1) in Kayin State, approved in 2018 with a USD 120 million loan; and the Second GMS Highway Modernization Project (GMS2) in southern Myanmar, yet to be approved with a USD 438 million loan.

The GMS2 will connect Bago and Kyaikto regions in southern Myanmar and in 2019 it completed preliminary examinations and assessments required for approval. This involves: (i) project planning and environmental assessment, (ii) EIA (where impacts are deemed vague), (iii) public consultation, and (iv) the government determining the resettlement and compensation scheme, before heading into (v) project implementation. This process hints that public consultation involving affected communities only takes place after project decisions are made and insufficiently, as was the case with the suspended GMS1 in Kayin state.

In the case of GMS1, a letter addressed to the ADB by civil society organizations (CSO) such as Karen Environmental and Social Action Network, IFI Watch Myanmar and Thwee Community Development Network implied that there was little space for negotiation in the compensation and resettlement plan. This suggests the project may go ahead without full consent of the affected communities on the resettlement and compensation plan.

Such public disapproval often prompts the ADB to halt or suspend projects against the government’s will. This was the case for GMS1 in Kayin state, where the ADB rejected the Chinese contractor that won the contract from the Ministry of Construction, due to their lack of environmental and social safeguarding in the use of Lun Nya Quarry. This quarry is located approximately 2km away from the project site and has been listed as one of the main sources for construction materials in the ADB’s Initial Environmental Examination. The quarry is licensed to Chit Linn Myaing Toyota, owned by the Tatmadaw-controlled Border Guard Force commander, Colonel Saw Chit Thu, but China Road and Bridge Construction, the aforementioned contractor, is reported to be operating the quarry as well. The lack of consultation and potential environmental and social damage that the quarry may have on the livelihoods of affected local communities led to mounting frustration. According to an article from Frontier Myanmar, the MoC is responsible for the highway construction and was aware of the conflict surrounding this quarry but disregarded the potential risks and ultimately allowed sourcing from the quarry for their project, without informing the ADB. Further complications arise from an amendment to the Mines Law, making it easier to mine with only approval from the General Administration Department. This makes it difficult to meet the requirements laid out by the ADB in sourcing construction materials that are environmentally and socially responsible, especially when a different ministry is responsible.

As we observe in this case, the ADB works closely with the MoC in implementing highway projects, but the ADB seems unable to manage risk due to local conditions. Examining the local political economy could help to better anticipate such risks, as infrastructure projects that are intended to empower communities can instead push them into more precarious states, with negative impacts not only from construction but also from the sourcing of materials.

Related

Rupture—conceptualising nature-society transformation

Sango Mahanty explains how mega infrastructure projects such as hydropower are dramatically transforming nature and society in our region.

While MDBs fulfill their role as risk regulators to a certain extent through their involvement in arranging the legislative framework for safeguarding, their projects often fail to meet safeguarding standards. MDBs seem to be helping the country work towards SDG Goal 9, but what we observe on the ground shows that promoting inclusive and sustainable development in Myanmar is no easy task.

These World Bank and ADB infrastructure projects highlight how environmental and social risks can emerge from MDBs’ lack of awareness of and responsiveness to local conditions. Both cases show a lack of acknowledgement of stakeholders, their relations, and the potential interests and threats that surround projects. As the suspension of the ADB’s GMS1 and the delay of the World Bank project are associated with some form of conflict, or the risk of it, the cases show a need to be aware of the political economy at the planning and assessment stage to be capable of mitigating risks that could potentially sabotage the project. Considering the context of Myanmar, which is a new and weak democracy within a corruption-prone landscape, risk mitigation based on an awareness of the local political economy is essential. MDBs must take on a more engaged “risk regulator” role rather than leave responsibility to the government.

Acknowledgement: some ideas for this article were formed when both authors studied the subject “Global governance and the role of Multilateral Development Banks” ANTH8107 convened by Dr Sarah Milne

[ad_2]

Source link