[ad_1]

Years after pledging to recover cleanup costs from those responsible for spreading lead pollution over thousands of homes in southeast Los Angeles County, California regulators have finally filed suit against multiple companies connected to the closed Exide Technologies battery recycling plant in Vernon.

The action notably excludes Exide, which under a recently approved bankruptcy plan was allowed to walk away from the half-demolished hazardous site and stick California taxpayers with much of the cleanup bill.

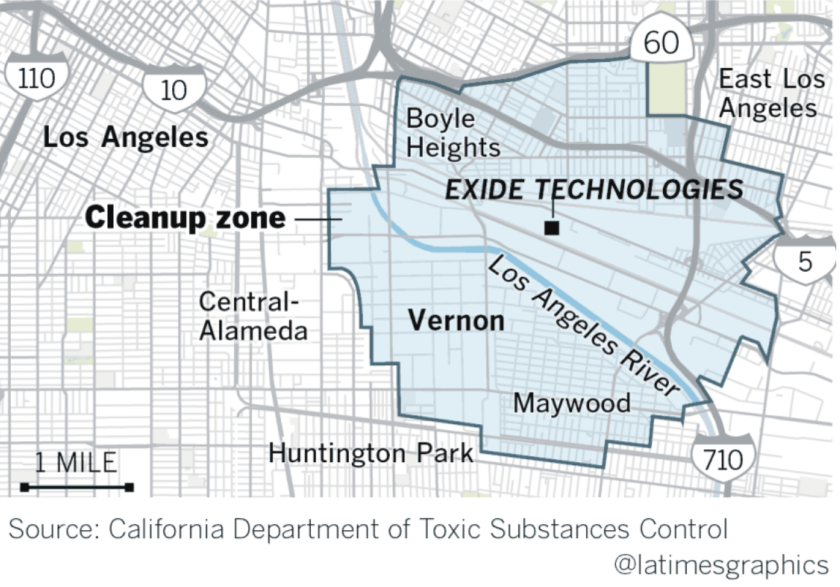

That angered community groups and environmentalists in the largely working-class Latino neighborhoods surrounding the plant, who reacted tepidly this week to news of the lawsuit, asking why it took so long and what it would change on the ground. More than six years into the cleanup effort, thousands of homes and other properties across a massive cleanup zone remain riddled with unsafe levels of brain-damaging lead while families wait for the state to remove contaminated soil.

“Anything that can help recover money and put it toward the cleanup is needed, but it feels like too little too late because the real responsible parties are already off the hook,” said Idalmis Vaquero, a member of the group Communities for a Better Environment who lives in a Boyle Heights apartment complex that has not yet had its soil cleaned.

In the complaint filed Monday, the state Department of Toxic Substances Control alleges that three companies, or their corporate successors, that were past owners or operators of the facility and seven companies, or their successors, that sent hazardous waste or arranged for its treatment or disposal there are liable for cleaning up the pollution under the federal Superfund law. The state seeks to recover more than $136 million it has spent on the cleanup since 2015, plus the future cost of cleaning lead, arsenic and other harmful pollutants left behind at the facility and in surrounding neighborhoods.

The 39-page suit names NL Industries, JX Nippon Mining & Metals and Gould Electronics as previous owners or operators of the plant or their successors. It names Kinsbursky Bros., Trojan Battery Co., Ramcar Batteries, Clarios, Quemetco, International Metals Ekco and Blount as companies or successors of companies that transported hazardous waste to the plant, arranged for it to be shipped there, or both. The lawsuit says those firms were identified on shipping manifests from 1988 to 2015. Exide operated the site from 2000 until its 2015 closure, and was responsible for cleaning up the mess left behind.

Kinsbursky Bros. Vice President Daniel Kinsbursky said that “KBI, like thousands of other companies, shipped recyclable materials to Exide’s Vernon site which California state regulators had for decades authorized Exide (and prior operators) to accept and process for recycling” and was never involved in the plant’s operations.

Patrick Dennis, an attorney for Quemetco, said the company “takes its environmental responsibilities seriously and looks forward to defending itself once the complaint is served and we have had an opportunity to investigate the allegations.”

Kari Pfisterer, a Clarios spokeswoman, said the company was aware of the suit but could not provide further comment on pending litigation.

Calls and messages requesting comment from the other companies were not returned.

Legal experts and environmental groups said that even if the state’s lawsuit succeeds, they expect it will take years for any money to be recouped and put to use cleaning contaminated homes, day care centers, schools and parks.

Protesters march from Boyle Heights to the Los Angeles Civic Center in October to demand accountability for pollution caused by the Exide battery recycling plant.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

The lawsuit marks the latest attempt to deal with government’s failure to protect the public from health-damaging pollution from the facility, a slow-moving disaster that has become a symbol of environmental injustice. Local leaders have called it California’s Flint, Mich.

Decades of air pollution from the plant, which operated about five miles from downtown L.A. melting down used lead-acid car batteries, is blamed for spreading lead dust over homes, yards, schools and parks up to 1.7 miles away. Lead is a powerful neurotoxin with no safe level of exposure. Even tiny amounts can cause learning deficiencies and other permanent developmental and behavioral problems in children.

California regulators had allowed the facility to operate without a full permit for more than three decades and did not require the company to set aside adequate funds to clean up its pollution, even as it racked up violations of hazardous waste and emissions rules.

Despite community outcry over the health risks and a flurry of investigations, no criminal charges were filed against the company or its employees. The company admitted to environmental crimes but avoided prosecution in a 2015 deal with the U.S. attorney’s office in exchange for permanently closing its plant. State and local prosecutors did not file their own charges.

As the size and cost of the cleanup ballooned, state Department of Toxic Substances Control officials assured the public for more than five years that they and the state attorney general’s office were “vigorously pursuing Exide as a responsible party” and would use “all legal avenues to recover costs” from the company and others responsible. The effort included extensive soil testing to prove the source of the contamination.

Department of Toxic Substances Control Director Meredith Williams said this week that her department had been pushing Exide to take responsibility for the cleanup through a separate, parallel process while it built its case against other responsible parties. She said the timing of the lawsuit was unrelated to the company’s bankruptcy and liquidation.

“Obviously Exide has evaded their responsibility,” Williams said. “I would also say that we’ve built as strong a case as we can and we are going to pursue this with the full intent of recovering funds.”

Toxic Substances Control spokeswoman Allison Wescott said the department secured tens of millions of dollars for residential and on-site cleanup work from Exide in 2014 but that a negotiated settlement agreement it entered into with the company that year “prevented DTSC from pursuing additional residential cleanup costs from Exide.”

In what has since become the largest cleanup of its kind undertaken in California, crews have removed lead-tainted soil from more than 2,100 of the worst-polluted properties over the last six years. But thousands more properties with lead contamination above state health limits have yet to be cleaned.

That work has been funded largely by taxpayers. The bill for the cleanup, already more than $250 million, could ultimately approach $650 million, a state auditor’s report estimated. That audit, released in October, found the cleanup was running behind schedule and over budget due to poor management by the Department of Toxic Substances Control and has left children at continued risk of poisoning.

Map shows the cleanup zone around the former Exide plant in Vernon.

(Los Angeles Times)

State Assemblyman Miguel Santiago (D-Los Angeles) said he and other lawmakers have for years been pressing for the department to take legal action against Exide and other companies responsible for the contamination.

“We are absolutely angry and frustrated that it’s taken this long,” he said. “This kind of emergency required warp speed and instead we got a sluggish pace at best.”

In the meantime, state lawmakers are seeking an additional $411 million in public funds to pay for residential cleanup, as well as new transparency measures to prevent cost overruns and delays. The money would be used to remove contaminated soil from thousands more properties and finish cleaning the Vernon site itself.

Lawmakers have also reintroduced legislation to reform the toxic substances department, which was passed earlier this year but vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom. Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens) said changes are needed to “prevent any future Exides.”

The type of lawsuit California filed is unlikely to satisfy community desires for justice because “it’s not about punishment. It’s about finding the money to pay for cleanup,” said Craig Johnston, an environmental law professor at Lewis & Clark Law School. “But the good news is there appears to be a lot of companies who are likely going to be held responsible.”

Johnston said it is “not unusual at all that people will take several years developing a complex Superfund case,” but that California officials at the same time “could have pursued criminal sanctions and cost recovery. These things are not mutually exclusive.”

Community members suffering from the pollution have for years demanded that those responsible be charged criminally, to no avail.

Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra’s office did not respond to questions about whether it investigated Exide criminally or pursued charges against the company. The L.A. County district attorney’s office spent years on a criminal investigation but did not file charges.

L.A. Dist. Atty. spokesman Greg Risling said other agencies, including local air quality officials, never presented “a case to our office for criminal filing consideration against Exide,” adding that “our office is unable to file criminal environmental pollution or contamination charges without a referral from a regulatory agency because we rely on the information they provide to us on these complex scientific cases.”

A spokeswoman for the South Coast Air Quality Management District, which regulated the facility’s emissions, said it “shared information” with the district attorney’s office and U.S. attorney’s office, and that “it is their decision whether to use that information to file a criminal action, a civil complaint or pursue a different action.”

The air district filed its own civil complaint against Exide in 2014 seeking $80 million for alleged violations of lead and arsenic emissions rules, a case that is ongoing and “currently stayed in state court pending the resolution of various bankruptcy issues,” spokeswoman Nahal Mogharabi said.

Vaquero, the Boyle Heights resident, said “everyone is just pointing the finger at someone else, when in fact each one had their role in protecting communities from Exide. And they didn’t do that.”

Barry Groveman, an attorney and former head of environmental crimes for the L.A. County district attorney’s office, said the lawsuit was a necessary, if late, step, but that the state’s position is compromised by its history of weak oversight of Exide and the role it played in allowing the facility to continue polluting for decades.

Groveman expects the companies targeted in the suit to challenge it, at least in part, by arguing that the state does not have clean hands and “may itself be liable for a portion of the cleanup costs as a result of its negligent management.”

Groveman, who in the past has represented the county, the L.A. Unified School District and other government bodies, also criticized state and local officials for failing to conduct a serious investigation into what went wrong with Exide and how to prevent similar failures in the future.

“This is going to be repeated because nobody has been held accountable,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link