[ad_1]

For Georgia’s grassroots organizers, the feverish weeks between now and Jan. 5aren’t just about getting eligible people excited to vote, again.

They’re about making sure those votes, cast in the state’s high-stakes Senate runoff elections, will count.

Georgia’s election code “is designed to be as restrictive as possible,” said Nsé Ufot, CEO of the New Georgia Project, a nonpartisan group that aims to register and engage new voters. “It is only through a massive, sophisticated, connected organizing campaigns and huge media narrative campaigns that we’re even able to make the kind of interventions that we need so that Black people and new Americans and women, quite frankly, can vote.”

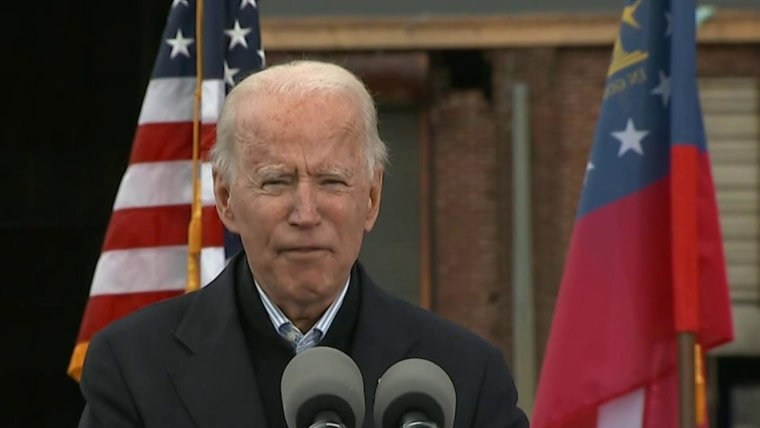

NGP, founded in 2014, and the many grassroots groups and activists who worked for years to engage voters in the state helped educate and mobilize voters while encouraging huge numbers to vote by mail during the pandemic. The resulting historic turnout helped push President-elect Joe Biden over the top by about 12,000 votes, flipping Georgia blue for the first time since 1992.

Now, with all eyes still on Georgia and party control of the U.S. Senate in the balance, voting rights advocates and organizers are working to keep that momentum going while highlighting the uphill battle they’ve fought against the parts of the state’s election code they say make it unnecessarily hard for some Georgians to cast a ballot. Adding to the political stakes, Georgia Republicans, echoing President Donald Trump’s false claims of voter fraud, have vowed even tighter voting restrictions in the new year, alarming voting rights advocates who say the state already has some of the strictest rules in the nation.

Right now, Georgia pairs the kind of reforms that typically make voting easier — automatic voter registration, early voting and no-excuse mail voting — with stringent rules like aggressive voter purge policies and strict voter ID laws that often make it harder, particularly for voters of color.

That makes Georgia a “mixed bag” when it comes to access, said Wendy Weiser, a leading national voting rights expert and vice president of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at the NYU School of Law.

Nineteen states have some kind of automatic voter registration, and 34 states have no-excuse absentee voting, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. According to that group, Georgia has slightly more than the average number of early voting days.

But to evaluate the fairness of election laws for all communities, Weiser said, restrictions must be carefully analyzed.

“Voting restrictions don’t fall equally on all voters. In Georgia, as in other states, they exclude Black and brown voters at higher rates, and maybe students,” Weiser said. “That can actually have an impact on election outcomes in close races.”

Experts point out that Georgia’s history of restrictive, discriminatory voting laws date back to literacy tests designed to disenfranchise Black voters after they were given the right to vote with the 15th Amendment.

For Ufot and other advocates, the devil’s in the details.

“The story of Georgia and Georgia elections is one of a canyon between the letter of the law and the spirit of the law — and how election law is enforced in our state,” Ufot said.

She ticked off examples: Automatic voter registration, considered by voting rights advocates a commonsense way to encourage more people to participate, only works for voters getting photo ID at the Department of Driver Services, something not all Georgians have.

Additionally, the state requires voters to register 29 days before Election Day — one of the earliest deadlines in the nation — but Ufot said counties don’t always process those registrations in that monthlong period.

In the past, she said, that’s left tens of thousands of voters registered by the NGP without the ability to vote despite filling out a voter registration form more than a month in advance.

Additionally, Georgia was one of the first states to implement a strict voter ID law at the polls in 2008, which in its initial form didn’t include any carve-outs for people who couldn’t afford the fees associated with state photo IDs. There are now several ways for voters to obtain a free photo ID. The state attempted to pass a law requiring proof of citizenship in certain voter registrations, until a court nixed it.

“There were a lot of people that were born in hospitals in rural Georgia, their information was recorded in a family Bible,” Helen Butler, executive director of the Coalition for the People’s Agenda, said. The coalition is a nonpartisan group that aims to engage and mobilize voters to participate in government.

Butler’s group uses door hangers to remind voters of important deadlines for requesting and mailing absentee ballots and early voting. They send organizers into communities to help educate them about the election process, and they give voters rides to the polls, too.

She said turning out voters is hard work and it shouldn’t be made harder with more barriers.

Advocates say the state’s aggressive approach to voter roll maintenance — which regularly purges voters from the books — makes it easy for eligible voters to inadvertently become disenfranchised. This month, the Black Voters Matter Fund, the Transformative Justice Coalition and the Rainbow Push Coalition sued, alleging that nearly 200,000 people purged during routine list maintenance last year were still eligible voters. They also challenged a law that tosses voters from the rolls if they do not vote or communicate with election officials for nine years.

And while many counties expanded the number of early voting sites in a big way in November, it’s been curbed in some areas for the runoffs. Georgia’s elections are largely administered on a county level, which means everything from early voting hours to the number of voting sites can vary greatly across the state.

Some counties made reductions to early voting, earning criticism and triggering at least five lawsuits from voting rights advocates who warned the changes could suppress votes, particularly harming Black and Latino voters. As a result, these advocates argued, long lines formed in Cobb County, the state’s third-largest, and turnout was down in the first few days of early voting.

Two Republican lawsuits have been filed to try to stop the use of unattended drop boxes, after Trump made still-unproven claims that the boxes lead to increased fraud. One suit was dismissed this week. Drop boxes, a common way for voters to securely return their absentee ballots without mailing them in, are provided by the counties and ballots are collected by election officials. They’ve been used for years without issue.

State legislators have also vowed to pass stricter voting laws, including requiring an excuse to vote absentee — undoing a system Republicans put in place years ago.

“Black people didn’t use the absentee ballot process until this year because they didn’t trust it. They believed that they had to go vote in person,” Butler said “When we trained them to do that now, our legislature wants to change all that — they want to make you have a reason for voting by mail.”

The lawmakers also said they would unwind a consent decree struck in 2020 between the stateand Democrats to standardize the signature matching policies used to verify people’s identity and eligibility. Voters of color have historically faced higher rejection rates than white voters when voting by mail.

Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, who has sought to balance assurances that fraud did not tar Georgia’s election with his own calls for additional voting restrictions, has also targeted groups including the New Georgia Project with an investigation, alleging they have repeatedly tried to register ineligible voters. Ufot has dismissed the investigation as “ridiculous.”

Marc Elias, the attorney who secured the consent decree, told reporters in a press briefing in Decemberthat he would go to court to keep Republicans from unwinding the consent decree and access to the ballot box.

“I will be spending a good chunk of my time in 2021 and 2022 fighting against this,” he said. “We will see them in court.”

[ad_2]

Source link