[ad_1]

Before they entered the emergency room in San Antonio in late September, Randy Hinojosa turned to his wife of 26 years and assured her that they’d both get better and see each other again.

“I said, ‘We came together. We leave together,” he recalls.

Hinojosa recovered from his bout of COVID-19, but his wife did not. Five weeks later, on Oct. 25, Elisa Hinojosa died of the disease.

Faced with a $15,000 bill for funeral expenses, Hinojosa, 52, paid it without hesitating, even though his own four-day hospital stay with the virus had set him back $5,000 and the pandemic had hurt his business as a self-employed contractor.

“I knew what I had to do as her husband and as her best friend,” he says. “I said I don’t care if I have a penny to my name. I’m going to make sure she has something nice that she deserves.”

When their three children were concerned that he was depleting his savings, Hinojosa turned to GoFundMe, where 114 people donated more than $9,000.

“I didn’t even want to ask anybody for money,” he says, breaking down in tears. “I had this pride that I could do this.”

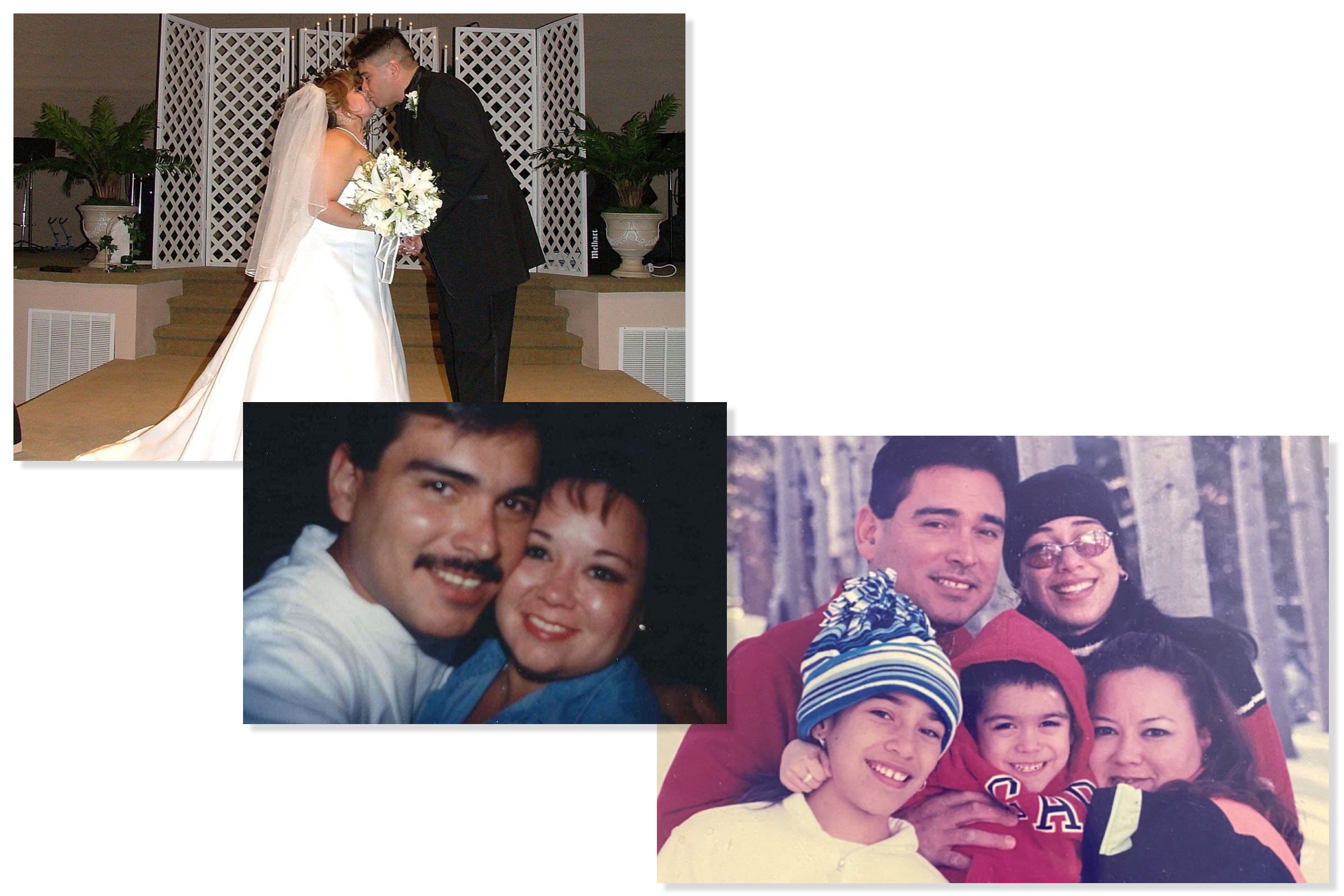

Randy Hinojosa and his late wife Elisa are pictured, top left, at their wedding in 2003. The two met 26 years ago. They share three children, including a 23-year-old son and two daughters, age 28 and 31. Elisa died of COVID-19 in a Texas hospital on Oct. 25.

Courtesy of Hinojosa Family

“You can’t die these days because it’s too expensive.”

As the pandemic worsens nationwide, add rising funeral costs to the problems facing low-income and working-class families, who have been disproportionately affected by both the economic and the health fallouts of COVID-19. A search on GoFundMe for campaigns related to COVID-19 funerals turns up more than 17,000 results. Many were created by or for people of color who, because of employment, housing and health care inequities, are more likely than white people to get sick and die from COVID-19, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and studies by other health authorities.

Read More: Lost in the Pandemic: Inside New York City’s Mass Graveyard on Hart Island

Crowdfunding is uneven, too. Some campaigns have raised nothing. Others have brought in far more than expected. In Los Angeles, Hannah Hae In Kim, 22, raised more than $650,000 on GoFundMe after losing both of her parents and her grandmother to COVID-19, leaving her financially responsible for herself and her 17-year-old brother Joseph. “I didn’t even expect it to hit $5,000,” Kim says. “I didn’t know so many people would be so willing to help out.” The windfall was fueled by attention in a major media market and donations from members of the family’s large church, many with the means to make contributions of $1,000 or more. “I’m trying to think of that money as the money our parents would have wanted to raise for us if they were alive,” Kim says. “But I would pay any amount to have them back.”

Kim with her parents in 2016.

Courtesy of Hannah Kim

“To think I have to live my whole life without my parents here with us, is crazy.”

More typical is a Georgia man who said he created a campaign to take care of his longtime friend’s family because he could not afford to help them himself. It drew more than $11,000. “This is the last thing that I can do for him,” he wrote. An appeal from a widow in Texas struggling to bury her husband raised less than $2,000. “I never thought I would be in this situation asking for help,” she wrote.

Other families are turning elsewhere for help, including to billionaires and politicians on Twitter. Some are simply not claiming the bodies of loved ones. In New York City alone, hundreds of COVID-19 victims who died in the spring remain in freezer storage trucks because their next of kin could not afford a proper burial, according to the city’s Chief Medical Examiner.

Hinojosa would rather go bankrupt than see that fate for his late wife. The couple was together nearly 30 years after meeting at a dance club, where he won her over with his dance moves and cowboy hat. “We danced for about 30 seconds without music, and I said that’s it. She’s the one,” Hinojosa recalls.

On his wife’s final day, Hinojosa says he begged doctors to take his own lungs and kidneys to save her, but they said it wouldn’t help Elisa.

The last image Hinojosa has of Elisa is his daughter wailing over her and fixing her mom’s hair. “I was with her for 26 years,” Hinojosa says, “and COVID took her away from me in five weeks.”

With help from the crowdfunding effort, Hinojosa was able to cremate his wife and pay for a live-streamed funeral service, a plot, burial and labor costs as well as a lifetime of cemetery lawn care. He reserved the plot next to her for another $10,000, which he’s paying in increments over the next five years. “You can’t die these days because it’s too expensive,” Hinojosa says.

That was true even before COVID-19 had killed more than 317,000 people in the U.S. and left tens of millions without jobs. Over the past five years, median funeral costs have increased 6% to $7,640, and a funeral with cremation grew 7% to $5,150, according to a 2019 report by the National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA). The figures do not take into account cemetery expenses or other charges, including flowers or an obituary. Even before the pandemic struck, the Federal Reserve found that 4 in 10 adults would struggle to cover a sudden expense of just $400.

In New Mexico, Michael Kellogg, 60, had to scrape together money after losing his wife—his high-school sweetheart—to the coronavirus on Nov. 8. Already reeling from pandemic-related unemployment and two major car repairs, Kellogg and his three children created a GoFundMe page to help pay for her funeral. The Native American family raised more than $5,200, mostly from friends and relatives, which was enough to cremate the 59-year-old matriarch without a service on Nov. 17. “We just needed help,” Kellogg says. “On the financial side, it doesn’t stop.”

“I gotta make the mortgage. I gotta pay the utilities,” he adds. “I don’t want to say it’s crippling, but it hampers you tremendously.”

Michael Kellogg (top right), his late wife Gloria (bottom center) and their three children pose for a 2015 family photo. Kellogg says the Farmington, N.M., family was laughing at his niece, who was telling jokes in the background. “That caught us in our natural setting,” he says.

Courtesy of Kellogg Family

“I gotta make the mortgage. I gotta pay the utilities.”

Even funeral homes are feeling the pinch. More than 53% of funeral homes in the U.S. said the pandemic has decreased their profits, according to an NFDA survey of 646 funeral directors in August. Randy Anderson, the association’s president, says that’s because so many cash-strapped families are opting for immediate burials and cremations over more expensive services.

In Los Angeles, for example, instead of selecting a full service that includes cremation, a casket and a funeral service for about $5,000, more families are choosing direct cremation with no funeral service for just under $2,000. “Because of COVID, people are choosing simpler funerals,” says Henry Kwong, managing director of two Los Angeles funeral homes, who estimates his profits have dropped about 10% to 20% since last year.

Read more: Three Days in a Detroit Funeral Home Ravaged by the Coronavirus

Funeral homes are also having to pay their staff overtime and spending thousands of dollars on extra cleaning services and costly protective gear. Anderson, who owns and runs a funeral home in Alexander City, Ala., says his overtime expenses have increased 13% and his supply costs have climbed 17% since 2019. He also spends an extra $2,000 a month to have an outside company disinfect his funeral home.

But while operating costs have increased, prices have stayed the same—for now. Kwong doesn’t know by how much he’ll have to raise rates in 2021 after this deadly winter, but he worries the impact of the pandemic will be felt for years to come. Nearly 90% of U.S. funeral homes are privately owned by families or individuals, according to the NFDA. Like many businesses across the nation, some could topple because of the pandemic, Kwong fears. “We have to tighten our belts,” he says. “It’s not a pretty picture.”

Like many who’ve died of COVID-19 in the U.S., Hannah Hae In Kim’s parents were on the low end of the economic ladder. Her father Chul Jik Kim moved to the U.S. from South Korea in the 1980s and eventually settled in California with his family. Kim remembers her mother waiting in line for hours to receive food stamps when they were living in Los Angeles, where her father juggled various jobs before becoming an acupuncturist.

Hannah Hae In Kim in Los Angeles, on Dec. 6, 2020.

Bethany Mollenkof for TIME

“I’m trying to think of that money as the money our parents would have wanted to raise for us if they were alive.”

They settled into an apartment in Koreatown, a densely packed and working-class neighborhood in central Los Angeles that today is mostly Latino, the city population group hit hardest by COVID-19. With businesses closing all around them, Kim realized that her family would have no income. Kim’s father knew it too, and to bring in a bit of money, he treated one or two clients. Kim thinks that’s how he got COVID-19.

The disease spread quickly in the family’s small apartment. Her 85-year-old grandmother fell ill about the same time as Kim’s father and died April 30. Her father, who was 68, died on May 21. By then, Kim, her brother and their mother Eunju Kim were infected. The siblings had mild symptoms, but Eunju Kim, 60, was sick enough to be hospitalized.

Kim realized the enormity of the situation—that she could be left alone to care for herself and her brother with no source of income—when her mother called from the ICU and, between gasps for air, told her to find and use the cash she hid in her wardrobe for emergencies. “I looked in there and it was $300,” Kim says. “I think it hit me then.”

Kim had been optimistic that her mom would recover. And for a time, she did get better. But like many COVID-19 patients, she relapsed suddenly and died on July 14.

“I thought I’d have to give my parents’ eulogies in my 40s or 50s,” Kim says. “To give both of them at the same time, to think I have to live my whole life without my parents here with us, is crazy.”

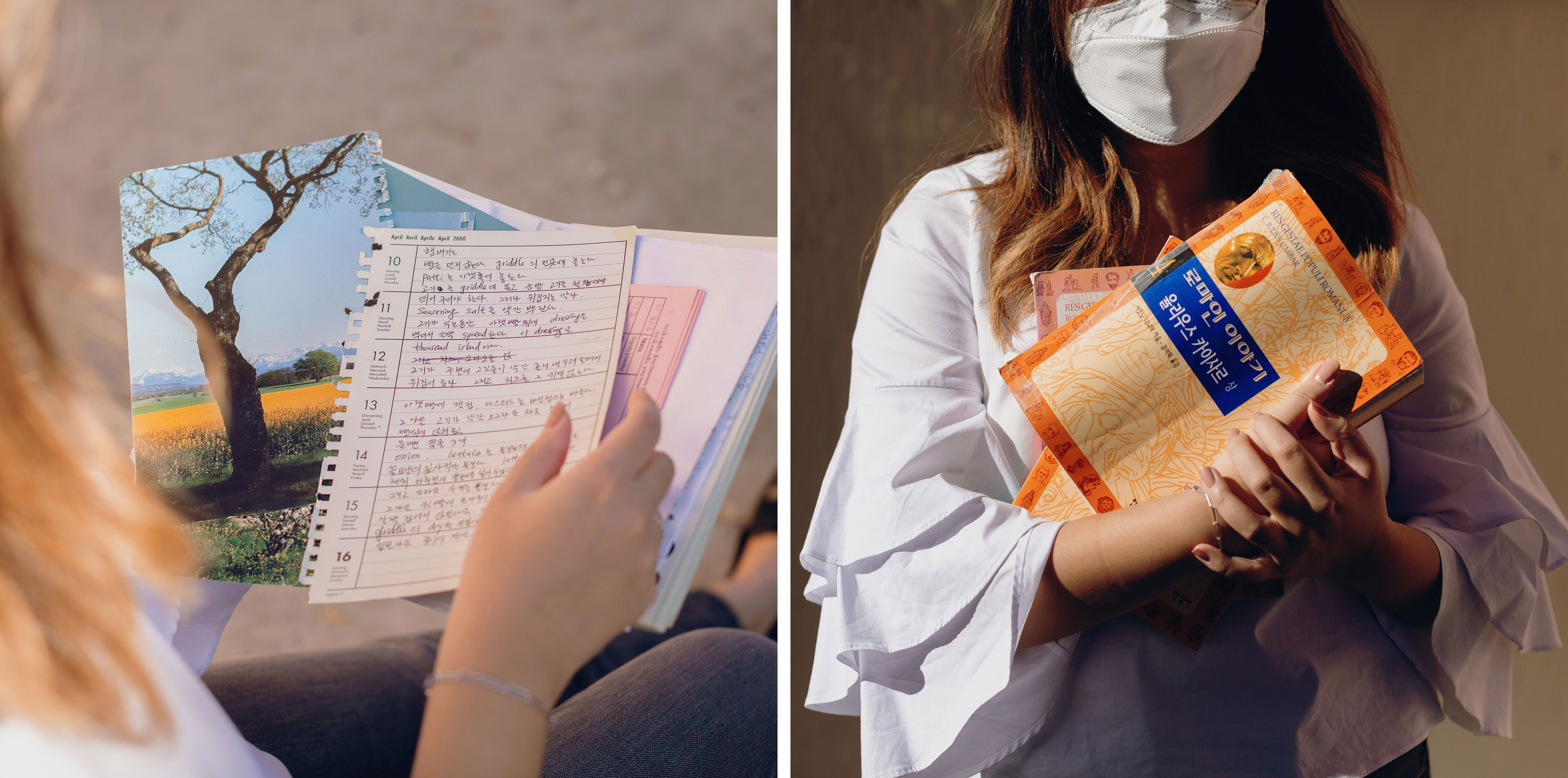

Hannah Kim holds her mother’s cookbook that is filled with handwritten notes and recipes; Kim holds her father’s favorite books

Bethany Mollenkof for TIME

Read more: One Month Inside a New York Hospital as a Virus Took Hold

Early in the pandemic, the federal government approved a series of measures meant to strengthen the country’s frail safety net, including $1,200 stimulus checks and enhanced unemployment insurance. But it did not address the issue of funeral costs. Some counties and cities have offered limited assistance, and several charities have stepped in to help, but none were set up to handle the level of need they’re now seeing.

“The phones start ringing around 7 a.m. and we average about 12 families a day,” says Angel Gomez, who founded the nonprofit Operation H.O.P.E. in El Paso, Texas. The organization, which is funded by donations, has helped cover more than $500,000 in funeral costs for more than 500 families since April.

“As the money comes in, the money goes out,” Gomez says. “People are hurting.”

“In the richest country in the world, we should be able to allow people to bury their loved ones in dignity.”

After three major hurricanes ripped through parts of the U.S. in 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency doled out about $2.6 million in funeral assistance, according to a 2019 report from the Government Accountability Office. But the agency has not yet allocated any funds for funeral assistance during the pandemic. A FEMA spokesperson said approvals are “made at the discretion of the President,” adding that President Donald Trump has only authorized the Crisis Counseling Program, which funds mental health assistance.

In April, Democratic lawmakers in New York, including Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, urged FEMA to take action, saying it was humane and the “very least” that officials can do. “And in the richest country in the world, we should be able to allow people to bury their loved ones in dignity,” Ocasio-Cortez said at a news conference. She later introduced a bill that would direct FEMA to create a COVID-19 funeral-assistance fund. A spokesperson for Ocasio-Cortez said the bill is still sitting in committee.

“We weren’t supposed to die.”

Hinojosa was used to making big financial decisions with his wife, but they hadn’t made end-of-life plans together because, he says in disbelief, “we weren’t supposed to die.”

That’s changed. After Elisa died, and after he was faced with the high cost of burying a loved one, Hinojosa shared his wishes for his own funeral with his grown children.

“Make mine as cheap as possible,” he told them. “Have the preacherman go to the cemetery, and save that money.”

[ad_2]

Source link