[ad_1]

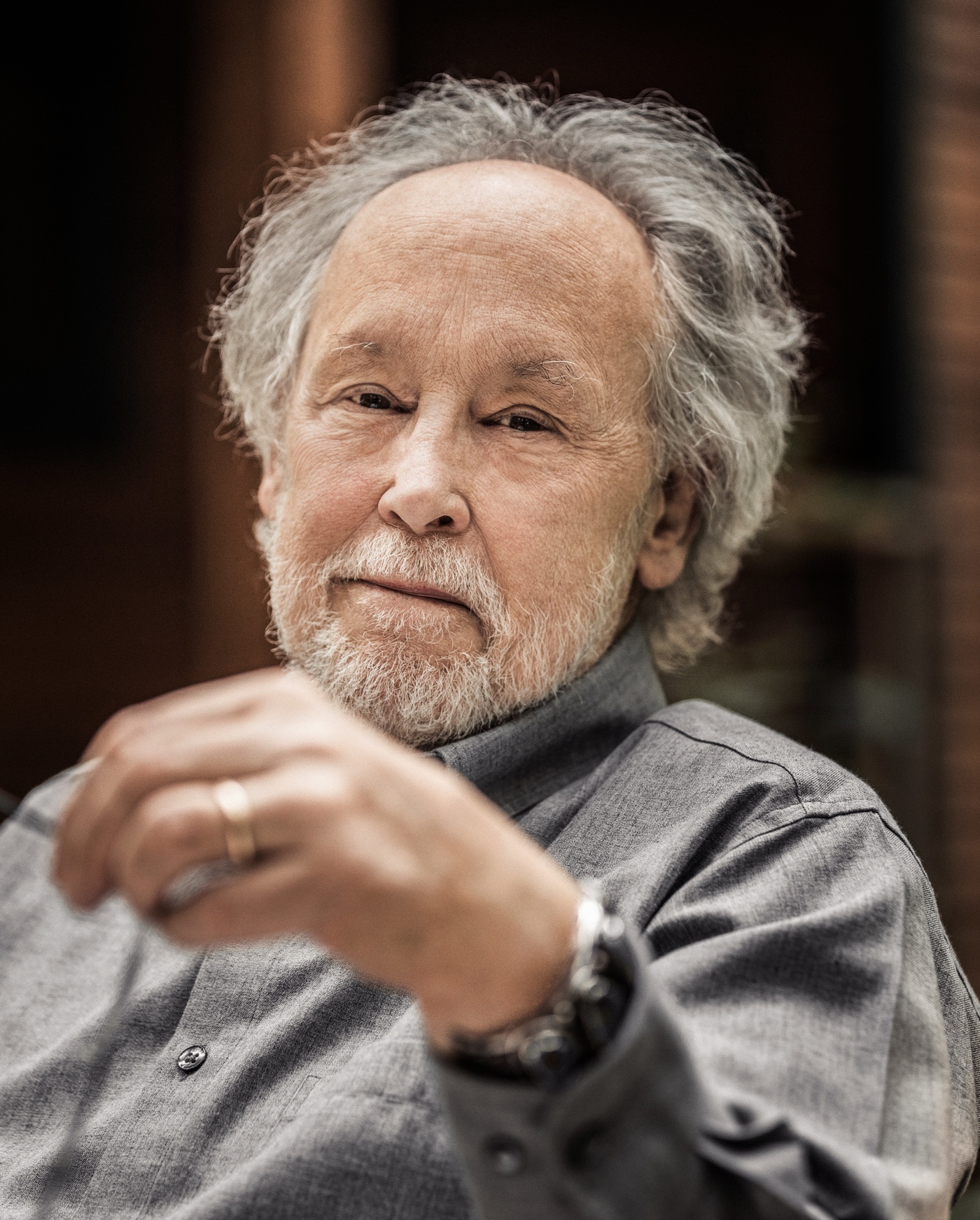

Barry Lopez won the National Book Award in 1986 for Arctic Dreams.

John W. Clark

hide caption

toggle caption

John W. Clark

Barry Lopez won the National Book Award in 1986 for Arctic Dreams.

John W. Clark

National Book Award winner Barry Lopez was famous for chronicling his travels to remote places and the landscapes he found there. But his writings weren’t simply accounts of his journeys — they were reminders of how precious life on earth is, and of our responsibility to care for it. He died on Christmas Day following a years-long battle with prostate cancer, his wife confirmed to NPR. He was 75.

Lopez spent more than 30 years writing his last book, Horizon, and you don’t spend that much time on a project without going through periods of self doubt.

When I met him at his home last year, he told me when he was feeling defeated by the work, he’d walk along the nearby McKenzie River.

“Every time I did there was a beaver stick in the water at my feet. And they’re of course, they’re workers. So I imagined the beaver were saying ‘What the hell’s wrong with you? You get back in there and do your work.'”

Up in his studio, he had a collection of the sticks, and he showed me how they bore the marks of little teeth. It was a lesson for Lopez. “Everyday I saw the signs of: don’t lose faith in yourself,” he told me.

This was the world of Barry Lopez — a world where a beaver could teach you the most valuable lessons.

Lopez was born in New York, but his father moved the family to California when he was a child. He would eventually settle in Oregon, where he gained notice for his writing about the natural world. He won the 1986 National Book Award for his nonfiction work Arctic Dreams.

At the time, he told NPR how he approached the seemingly empty Arctic environment.

“I made myself pay attention to places where I thought nothing was going on,” he said then. “And then after a while, the landscape materialized in a in a fuller way. Its expression was deeper and broader than I had first imagined that at first glance.”

In Lopez’s books, a cloudy sky contains “grays of pigeon feathers, of slate and pearls.” Packs of hammerhead sharks in the Galapagos move “like swans milling on a city park pond”

Composer John Luther Adams was friend and collaborator of Lopez for nearly four decades He says Lopez’s writing serves as a wake-up call.

“He surveys the beauty of the world and at the same time, the cruelty and violence that we humans inflict on the Earth and on one another, and he does it with deep compassion,” Adams says

Lopez experienced that cruelty firsthand: As a child he was sexually abused by a family friend. He first wrote about it in 2013, and he later told NPR the experience made him feel afraid and shameful around other people. The animals he encountered in the California wilderness offered something different.

“They didn’t say ‘oh we know what you went through,'” he said. “I felt accepted by the animate world.”

Lopez would spend his life writing about that world — in particular the damage done to it by climate change.

That hit home for Lopez this past September. Much of his property was burned in wildfires that tore through Oregon, partly due to abnormally dry conditions. His wife Debra Gwartney says he lost an archive that stored most of his books, awards, notes and correspondence from the past 50 years, as well as much of the forest around the home.

“He talked a lot about climate change and how it’s so easy to think that it’s going to happen to other people and not to you,” she says. “But it happened to us, it happened to him personally. The fire was a blow he never could recover from.”

When I spoke to Lopez last year, he said he always sought to find grace in the middle of devastation.

“It’s so difficult to be a human being. There are so many reasons to give up. To retreat into cynicism or despair. I hate to see that and I want to do something that makes people feel safe and loved and capable.”

In his last days, Lopez’s family brought objects from his home to him in hospice. Among the items: the beaver sticks from his studio.

This story was edited by Rose Friedman and adapted for the Web by Petra Mayer

[ad_2]

Source link