[ad_1]

The bifurcated economy that took shape in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic destroyed the lives, savings and small businesses of innumerable Americans, but the year wasn’t a financial washout for everyone.

Between roughly mid-March and Dec. 22, the United States gained 56 new billionaires, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, bringing the total to 659. The wealth held by that small cadre of Americans has jumped by more than $1 trillion in the months since the pandemic began.

According to a December report issued jointly by Americans for Tax Fairness and the Institute for Policy Studies using data compiled by Forbes, America’s billionaires hold roughly $4 trillion in wealth — a figure roughly double what the 165 million poorest Americans are collectively worth. The 10 richest billionaires have a combined net worth of more than $1 trillion.

America’s 659 billionaires hold roughly $4 trillion in wealth — roughly double what the 165 million poorest Americans are collectively worth.

It’s a stunning snapshot of how the pandemic has distorted large sections of the real economy and exacerbated the nation’s stubbornly persistent economic inequality — one that persisted, largely along racial and ethnic lines — even in a pre-pandemic economy with unemployment at a half-century low.

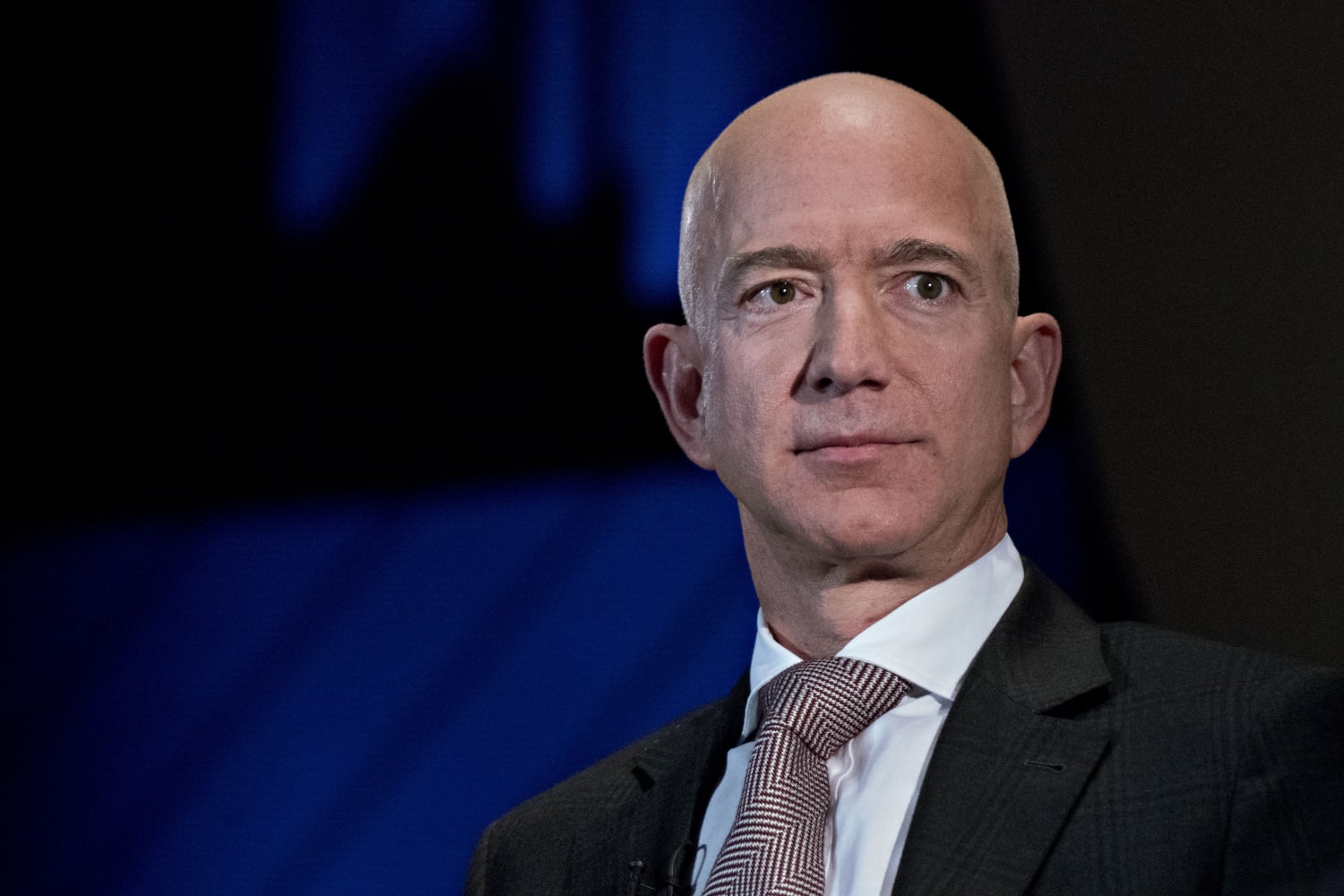

This roundup of the stratospherically rich includes familiar names like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Bill Gates, and emergent billionaires include Kanye West and Tyler Perry.

These entertainers are notable exceptions, though.

Most of the new entrants to the billionaires’ list aren’t household names, and for many, the stock market gets much of the credit for their burgeoning net worth. MacKenzie Scott, whose 2019 divorce from Bezos netted her a spot on the list under her own name for the first time, is one example of how the market has made the rich even richer. At the time of her divorce, Scott’s share of Amazon stock was worth around $38 billion. Now, less than a year and a half later, her net worth is estimated by Forbes to be nearly $59 billion. (Scott has made headlines in the ensuing months for her commitment to philanthropy and generous, no-strings-attached donations to nonprofit organizations and educational institutions.)

“Billionaires who started these companies and had a huge stake in these companies did really well this year,” said Frank Clemente, executive director of Americans for Tax Fairness.

A key driver of billionaire wealth concentration was the unprecedented monetary policy response to stabilize financial markets in the early days of the pandemic, which spurred the stock market’s gravity-defying rise. When Wall Street was on the verge of panic in March, the Federal Reserve intervened with the promise of low rates and an open-ended liquidity spigot.

“That gave market participants the assurance that the market volatility would be met with an enormous amount of force, and liquidity can be the salve for most economic wounds,” said Keith Buchanan, portfolio manager at Globalt Investments.

The combination of easy money and an abrupt shift in economic activity that favored digital commerce, communication, education and business activity gave technology firms — both startups and big companies — an unexpected tailwind.

“There are companies whose competition has been shut down, who have benefitted from the sequestering of Main Street enterprises,” said Chuck Collins, director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. “Wall Street is making big bets on who the winners are going to be coming out of the pandemic, and you’ve got a group of companies that have reaped windfalls.”

Beneficiaries of the stay-at-home economy include many of the year’s biggest IPOs, like Airbnb and DoorDash — and top executives at these and other high-valued IPOs, like cloud data company Snowflake, are among the new crop of 2020 billionaires.

In 2020, 217 companies went public and raised a little over $78 billion, a high-water mark not seen since 2004, said Kathleen Smith, principal at Renaissance Capital, an investment and research firm that developed an IPO index.

“The returns on the companies that have gone public have encouraged a lot of other companies to tap the market,” she said, adding that an ETF her firm created to track the performance of that index is up 120 percent for the year. “If investors make money, they’ll come back for more,” she said.

Some worry that this torrent of money into the tech sector is coming at the expense of America’s small businesses, and warn about the risks of concentrating economic power within a smaller base. “You have these big pools of capital looking for the biggest returns, the biggest bets — they’re not interested in the Main Street, they’re not interested in the real economy. They’re just trying to extract the biggest returns,” Collins said. “I think you’re going to see the implosion of vibrant Main Street commerce districts unless we reinvest in our local enterprises.”

Businesses with fewer than 500 employees contribute nearly two-thirds of the nation’s jobs and have struggled to fund their ongoing operations in a way larger companies have not experienced.

“We’re seeing a bifurcation between large multinational corporations and what we’re seeing from a Main Street economy on the ground,” Buchanan said, noting the increase in temporary business shutdowns becoming permanent. “Their closures benefit large corporations from a market share standpoint, but that doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” he said. “There’s a corporate inequality that has been present but has only grown that much worse.”

That inequality threatens to undermine healthy market competition both now and in the future as more small- and medium-sized businesses are forced to close their doors and consolidation accelerates. “I think it’s a really troubling indicator that certain companies will see their monopoly power increase,” Collins said.

The divide between the haves and have-nots among American families also has been widened by the pandemic, and will be exacerbated by the loss of Main Street jobs.

While pension funds and retirement plans are among the beneficiaries of rising valuations, Americans with no exposure to the market — roughly half the country’s population — have missed out on the gains.

“If you’re not an investor and you don’t have savings that benefit from it, those people have not benefited from it,” Smith said.

[ad_2]

Source link