[ad_1]

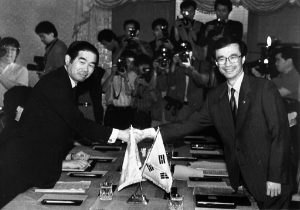

Japanese Foreign Minister Muto Kabun, left, shakes hands with his South Korean counterpart Han Sung-joo prior to meeting at the latter’s office in Seoul, Tuesday, June. 29, 1993.

Credit: AP Photo

The incoming Biden administration faces the unenviable challenge of reconciling two of the United States’ critical allies in the Indo-Pacific: South Korea and Japan. As many analysts have pointed out, stronger trilateral cooperation between the U.S., South Korea, and Japan would better secure all three states’ interest in a secure, stable, and prosperous Indo-Pacific. Nevertheless, historical, territorial, political, and economic disputes continue to undermine this relationship.

Despite these challenges, history suggests that the United States can encourage stronger South Korea-Japan relations through patient diplomacy. Repeatedly, the U.S. has been able to employ its strategic weight as both states’ paramount military ally to nudge these partners toward closer alignment. Policies that reinforced the United States’ value and credibility as a partner often undergirded U.S. entreaties, inviting reciprocal South Korean and Japanese steps toward deeper trilateral cooperation.

The Johnson administration’s efforts to secure the 1965 normalization treaty between South Korea and Japan provides a case in point. In the early 1960s, the regional security environment in East Asia had deteriorated due to China’s acquisition of nuclear weaponry and the escalation of the war in Vietnam. In the face of these threats, the Johnson administration sought to forge a closer relationship between its regional allies, including Japan and South Korea, to contain communist aggression. As the South Korean and Japanese governments navigated the contentious negotiations surrounding normalization, the United States continually emphasized to both allies its interest in strengthened South Korea-Japan ties.

This diplomatic push was reinforced by strong U.S. relations with both allies. The Kennedy and Johnson administrations had previously invested considerable effort in bolstering ties with Japan, emphasizing that the United States would consult with Japan as an equal rather than dictating to it as a subordinate. This outreach built goodwill in Tokyo, goodwill which the Johnson administration was able to capitalize upon as it pushed for the normalization treaty. Just as importantly, the Johnson administration repeatedly reaffirmed the United States’ commitment to South Korean security, making it clear that strengthened South Korea-Japan ties would be met with continued U.S. military and economic support for its partners. Ultimately, U.S. diplomacy helped pave the way for the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea, signed in June of 1965.

The Reagan administration similarly helped facilitate a rapprochement between South Korea and Japan in the 1980s. With the Reagan administration offering gentle encouragement, South Korean President Chun Doo-hwan and Japanese Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro held the first Korea-Japan summits in 1983 and 1984, paving the way toward a better relationship. During these summits, Nakasone agreed to a sizeable economic assistance package for South Korea and publicly emphasized the importance of the Korean Peninsula to Japanese security. South Korea’s presidential secretary general thanked the White House afterwards, arguing that it had contributed to this progress in Korea-Japan relations.

This U.S. effort to encourage stronger South Korea-Japan ties was undergirded by President Ronald Reagan’s reversal of the Carter administration’s ambivalence toward the U.S.-South Korea alliance. While President Jimmy Carter had called for the withdrawal of U.S. forces from the Korean Peninsula, Reagan doubled down on the United States’ commitment to South Korean security. Reagan similarly reaffirmed U.S. support for Japan while simultaneously calling on Japan to reciprocate by doing more to advanced allied security in Asia. Overall, Reagan’s firm support for both U.S. allies better positioned his administration to call on South Korea and Japan to reciprocate with closer cooperation of their own.

In the late 1990s the United States again led the way in bolstering trilateral relations, this time by creating the Trilateral Coordination and Oversight Group (TCOG). Launched in 1999, this group brought together U.S., South Korean, and Japanese policymakers in order to align their policies toward North Korea. Although tensions over Pyongyang’s nuclear program had been temporarily resolved by the Agreed Framework in 1994, North Korean missile-testing increasingly alarmed U.S., South Korean, and Japanese policymakers. In response to these concerns, the Clinton administration launched the “Perry Process” headed up by former U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry, a policy review incorporating close consultation with both South Korea and Japan. This review would ultimately produce the TCOG. While the TCOG would, over time, evolve from a high-level dialogue to a venue for working-level discussions, it nonetheless represented a significant institutionalization of the trilateral relationship.

The Clinton administration’s strengthening of its commitment to and cooperation with both Tokyo and Seoul gave greater weight to its push for trilateralism. The “Nye Initiative,” launched in 1994 and named for U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs Joseph Nye, clarified that the United States would retain a large military presence in Asia despite the end of the Cold War in order to maintain regional security. The initiative emphasized the critical importance the U.S. attached to its alliances with both Japan and South Korea. The United States also worked to upgrade its alliance with Japan, releasing revised Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation in 1997. These policies helped reinforce U.S. credibility as an indispensable partner for both South Korea and Japan.

It is important to note that while the United States played a key role in encouraging closer trilateral relations in each of these cases, none of these accomplishments would have been possible without political will and strategic vision in both Tokyo and Seoul. In each case, the president of South Korea and the prime minister of Japan were willing to move forward with closer ties even in the presence of unresolved disputes over history, reparations, and territory. Furthermore, stronger cooperation in each case was driven by more than just U.S. encouragement; South Korea and Japan were often responding to shifting economic opportunities, threat perceptions, and political openings. Nevertheless, in each instance the U.S. was able to make use of its strong alliance relationships with both states in order to pressure and cajole them into deeper trilateral cooperation.

Today, the incoming Biden administration has a new opportunity to incentivize its partners to move toward stronger trilateral ties. The outgoing Trump administration allowed trilateral cooperation to languish and undermined bilateral ties with both South Korea and Japan by fixating on disputes over trade imbalances and host-nation support. The Biden administration can help right the ship, reaffirming the critical importance the U.S. attaches to its alliances with South Korea and Japan. As the administration begins to mend fences with these partners, it should be well-positioned to encourage both Tokyo and Seoul to recommit to trilateral cooperation.

Erik French is an assistant professor of international studies at the State University of New York at Brockport. He earned his PhD in Political Science from Syracuse University.

Jiyoon Kim is an acclaimed political analyst specializing in election and public opinion analysis and US politics. She earned her PhD in Political Science from MIT.

Jihoon Yu is a lieutenant commander in the ROK Navy and a professor of military strategy at the ROK Naval Academy. He earned his PhD in Political Science from Syracuse University.

[ad_2]

Source link