[ad_1]

Eight years ago, when Oriel María Siu found out she was pregnant with her first child, she immediately began hunting for children’s books.

She riffled through dozens in the aisles of Seattle libraries, growing frustrated over the trite, predictable narratives she found on the shelves: white boys and girls were ubiquitous; children of color often played secondary characters; gender stereotypes and Eurocentric perspectives abounded.

Books she found about diversity were frequently shallow; she vividly remembers one that “reduces brown culture to nothing more than a piñata party on Cinco de Mayo attended by happy people who eat tacos. And the tacos don’t even look like real tacos!”

None of the books addressed the real experiences of children like hers, or the child she had been decades ago when her family was forced to flee Honduras. Or those who’d been separated from their parents.

Siu, an ethnic studies professor who earned her PhD from UCLA, decided to write a children’s book of her own. In May, she published “Rebeldita la Alegre en el País de los Ogros,” with illustrations by her sister, muralist Alicia María Siu, under Los Angeles-based Izote Press. The English translation, “Rebeldita the Fearless in Ogreland,” will be out in February.

“Rebeldita la Alegre en el País de los Ogros” was published last year by Izote Press, and it will be released in English in February.

(Oriel María Siu)

The story follows Rebeldita, a happy, fearless girl of Indigenous and African descent who was born “detrás de un gran muro,” “behind a high wall that looks over with a sneer” — a wall built by land-stealing Ogres 500 years ago. Her parents trekked over deserts and mountains to cross it, with Rebeldita held tightly in her mother’s arms.

One day at school in Ogreland, Rebeldita sees her friend Florecita crying. The Ogres snatched her parents the night before, Florecita tells her, locked them up in cages and sent them far away. Enraged, Rebeldita organizes her friends to fight back against the Ogres and their sharp-toothed dogs and reunite Florecita and other children with their parents.

When Siu submitted her book to Izote Press publisher Mario Escobar, it struck a chord immediately.

“It transmitted that pain that immigrants know about, the images, the story,” said Escobar, who went on to edit “Rebeldita.” Born in El Salvador, Escobar was 10 when he joined a group of fighters during the civil war after his father was killed. His grandmother and cousins also died in the war. He fled the country in the early 1990s, when he was 13, and crossed the border alone to join his mother in Los Angeles.

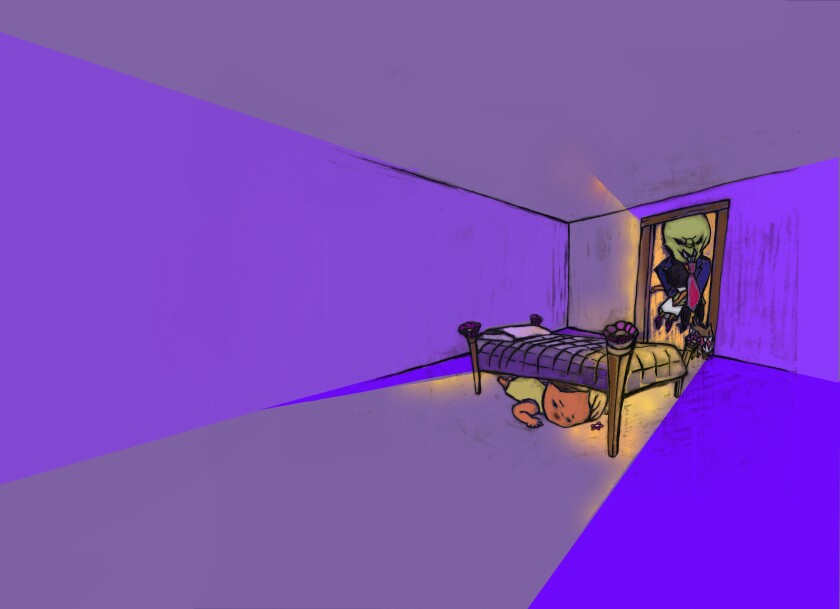

Florecita hides from an ogre under her bed.

(Alicia María Siu)

In 2004, Escobar applied for political asylum as an undergraduate student at UCLA. Not only was he denied; he was told he would be deported. Two years later, with the help of an attorney, asylum was finally granted.

“I could’ve only imagined what my daughter would’ve felt if I had been deported,” he said in a phone interview. “Bringing the story to light, to our children, is opening their eyes and making sure that history doesn’t repeat itself.”

With “Rebeldita,” Siu hopes to expose the personal toll of U.S. immigration laws, including the separation of thousands of children from their parents at the southern U.S. border under the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy. As of October, the federal government still couldn’t locate the parents of 545 children. Most of the parents, attorneys believe, were deported.

The policy has dire psychological effects. Depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder were reported in parents and children months after they were reunited.

The book is “about children finding the power to change the reality that they live in on their own,” said Siu, who dedicated the book to her nephew, Ayotli, 10, and her daughter Suletu, 7. (They played important roles in the writing process, offering feedback, calling out lines and posing for illustrations).

“At the heart of ‘Rebeldita’ is the whole entire humanitarian crisis of refugees and why people are being displaced,” said the illustrator, Alicia Siu. “They are forced displacements because our homelands are under assault [from] these ogres that have a face: They’re dictators, they’re narco cartels, they’re elite families and extractivist companies.”

An ogre and his vicious dog walk away with a caged child in Ogreland.

(Alicia María Siu)

Alicia’s illustrations underscore the institutions the sisters hold responsible and they extend far beyond the outgoing administration: “Wallogro Street” stands next to “Ogrump Tower.” Beneath a billboard that reads “Tome Coca-Cogra” (drink Coca-Cogra) is the bank “Fondo Monetogro Internacional.” Above the famous “Hollogrywood” sign is another that reads: “El país de ogros solo para ogros.” Ogre country only for ogres. Everywhere Rebeldita looks, she is reminded she’s in Ogreland.

But Rebeldita refuses to accept that world. She honors her roots, wearing a bandana common among indigenous people in Honduras, and a dress with patterns worn by the Ngäbe people from Panama. They’re symbols of resistance, Alicia explained.

As for the greedy green ogres in suits and ties, they represent “patriarchal, colonial, invasive, alien behaviors,” said Alicia. And they are anything but powerful. “They’re actually weak because they require force, which would be, in the real world, weapons and armies, and in the story, it’s the dogs.” These look scary and extraterrestrial, with red eyes and sharp fangs.

For translator Matthew Byrne, it is an important story for English speakers to read. “Family separation is a topic that will haunt us for many years after Trump,” said Byrne. “It was with us before Trump, and it’s certainly not going to disappear come Jan. 20.”

Rebeldita and her friends free the families in cages.

(Alicia María Siu)

Family separation is not a partisan issue or a new one for Siu. “It’s at the core of what the United States is” — from slavery to colonization to the arrival of Christopher Columbus, a.k.a. “Christopher Cologre,” “the first Ogre to come to the Americas.” Columbus will be the subject of a forthcoming Rebeldita sequel, which will feature, among other secret weapons, “a big, big fart.”

Siu is working on the new book in the town where she grew up, San Pedro Sula in Honduras. Born in 1981, Siu saw the country’s political and economic situation deteriorate as a child. In the wake of civil war, violence was met with impunity. Sweatshops exacerbated poverty. Mara Salvatrucha, the gang known as MS-13, was gaining strength.

In 1997 when Siu was 16, her family was held hostage in their home. The assailants believed that her parents, both doctors, had money in the house.

Her parents realized they had to flee, but they only had enough money to send one person away. Two weeks later, Siu was in L.A., living with her grandparents. “I hadn’t even seen a map of L.A. when I arrived.” Her family, who had legal status in the U.S., joined her the following year.

Oriel Mar´ía Siu and her daughter, Suletu Ixakbal, in Los Angeles.

(Courtesy of Oriel María Siu)

In June, Siu left teaching full-time, packed her bags and moved to San Pedro Sula with her daughter to write books two and three of the “Rebeldita” series. “I needed to get away from L.A. to write because it was financially impossible to sustain life and pay rent and write at the same time.”

Working on children’s books in the midst of a pandemic and hurricanes Eta and Iota, which devastated Central America in November, hasn’t been easy. Internet service has been sporadic. She has also taken time away from the books to help hurricane victims.

But Siu is determined to complete her mission as an author: to “undo a lot of the fairy tales that make up the history and narratives of what the United States is.”

[ad_2]

Source link