[ad_1]

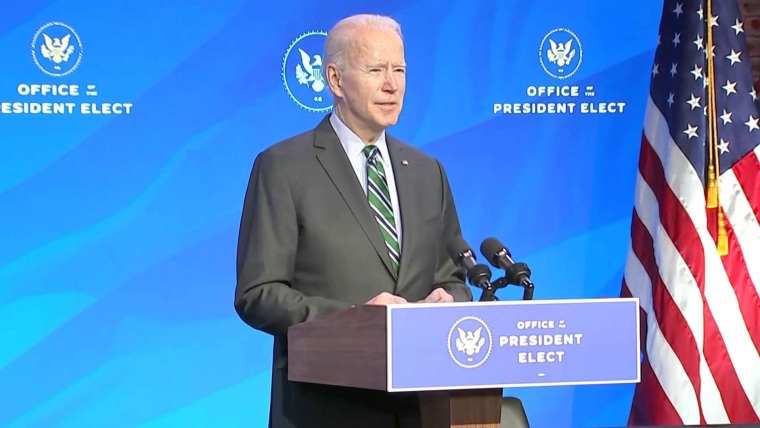

WILMINGTON, Del. — It was November when the word “ascertainment” entered the political lexicon as the bureaucratic barrier for Joe Biden’s ability to formally begin his transition. But the term was a front-of-center concern for months inside the Democrat’s under-the-radar planning team, so much so that in late June its executive director, Yohannes Abraham, emailed an outside expert requesting a full briefing on the potential ramifications — and began developing a game plan for how they could move ahead without it.

The ascertainment question, only settled three weeks after Election Day, was just one of several potential barriers Biden’s team had to consider. They referred to them as the “extraordinary challenges” — largely but not exclusively Trump-related headaches that would need to be addressed if the already-daunting task of standing up an administration in just 11 weeks would have any chance of success.

But against those odds, when Biden takes the oath in two days he’ll have an administration with more key positions filled than some of his recent predecessors had, and a policy process ready to tackle the multiple challenges he’ll face.

“Very few people do rigorous contingency planning just because there’s already enough to do, and why stare into scenarios that could make it more difficult? But low and behold, we were ready,” said Jeffrey Zients, one of the earliest hires Biden made for his transition 10 months ago, who in turn quickly tapped Abraham as his executive director.

“He was essentially orchestrating that series of plays to get past the early obstruction,” said Jake Sullivan, Biden’s incoming national security adviser.

Even when most agencies did begin meeting with Biden representatives, known as Agency Review Teams, the Defense Department and the Office of Management and Budget — two of the most critical — were outliers. While Abraham worked quietly to address this with his White House counterpart, Christopher Liddell, he also launched a public offensive to build pressure on the White House.

In a briefing with reporters, the low-key 35-year-old used what for him counted as unusually spicy language as he blasted the “pockets of recalcitrance” standing in the way of the kind of smooth transition the nation needed, and potentially put America’s security at risk.

“The thing about Yo is, he’s good at designing plays but he’s also good at running them,” Sullivan said. While cooperation with Pentagon officials is still not where it should be, Sullivan said it’s “substantially greater than it was before in no small measure because he took a hard headed relentless approach.”

The uneven cooperation from the Trump administration was hardly the only hurdle facing Biden’s team. They also had to adapt their entire approach to comply with stringent Covid-19 protocols — one of several factors, including the ascertainment delay in releasing taxpayer funds, that required them to ramp up private fundraising to set a new record for any transition committee.

The initial 10,000-square foot workspace provided to the transition in September, and the larger 175,000-square foot space post-ascertainment largely went unused. Full-time paid staffers and volunteers worked largely from home.

Once authorized to do so, Agency Review Teams held more than 5,000 meetings with federal agencies and congressional officials. A team of 200 staff and volunteers interviewed more than 7,500 people to fill thousands of administration jobs — and had a plan in place to begin identifying and vetting personnel even without the federal resources that later came in to support them.

Through Sunday, Biden had nominated 44 Senate-confirmed officials — besting Barack Obama’s mark by the same point in his transition, which had been the most recent high. The transition has also announced 206 White House staff — more than the last three incoming presidents combined.

And a particular focus of the Biden transition were positions that do not require Senate confirmation — ranging from the director of the CDC to department chiefs of staff, general counsels, and chief operating officers who are essential to laying the groundwork for quick action. David Marchick, director of the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition, said Biden’s team will have two to three times what previous administrations have had in place.

“This is the most productive transition from a personnel perspective in history, despite the late start and the challenges associated with the outgoing president,” Marchick said, crediting Abraham in particular for his role. “The degree of difficulty of any transition is very high. But this transition had the highest,” he said. “You have the various crises — economic, health — and then you layer on top of that the political uncertainty with Trump.”

As Biden prepares to be inaugurated, Abraham is transitioning himself — to his role as chief of staff for the National Security Council. Multiple Biden officials said Abraham’s work on the transition led to something of a bidding war among principals to bring him on for a number different agency roles.

It was the same nearly a year ago as Jen O’Malley Dillon, who took over as Biden’s campaign manager in March, tried to bring Abraham on in a senior role.

Abraham stayed with the fledgling transition, though, developing a routine with Zients that became the basis for work moving forward. Each week began by identifying goals for the week ahead and reviewing closely-monitored performance metrics from the prior week, everything from staff recruitment, fundraising, and diversity.

Abraham’s responsibilities multiplied after the election, particularly once Zients was appointed to oversee the Biden administration’s pandemic response. In addition to managing the day-to-day transition activities, he served as part of a team interviewing Cabinet and sub-Cabinet appointees, meeting with lawmakers and outside stakeholders to incorporate their priorities and suggestions.

The transition’s success in filling most key West Wing positions, officials say, has been critical to launching their ambitious first-week policy push. Naming Ron Klain as chief of staff, then Susan Rice to lead the Domestic Policy Council, Brian Deese to lead the Economic Council, Sullivan the National Security Council, Gina McCarthy the climate task force, and Zients the Covid-19 response team, shifted most — but not all of the burden away from the transition to those officials to build on the planning already in place.

That itself was a lesson learned from previous transitions, minimizing first the typical conflicts between campaign and transition, and then between transition and administration to ensure Biden’s team is faithful to what the campaign promised to deliver.

“We’re obviously operating in a highly uncertain moment and a crisis moment from the perspective of the economy, and so having this transition policy team in place with the breadth and the dynamism they have is absolutely essential to us being able to operate effectively. And that is a credit to the structure in the process that Yo and Jeff and the team built,” Deese said.

While officials credited Abraham with building what one called a “technological marvel” to monitor progress toward completing countless tasks, Abraham never managed to plug in his only television at home — a purposeful way of staying away from cable chatter, and setting a tone for the transition more broadly to keep their heads down and focus on the task at hand.

“All of this work behind the scenes of hiring people, interviewing people, getting policy processes ready — it’s not as sexy,” said Jen Psaki, the incoming White House press secretary. “But what worked for the campaign and what I think is working for the transition is we’re just going to do our business, and we’re keeping the noise out. And I think that’s part of the tone that set in the morning meetings and in our evening wraps.”

[ad_2]

Source link