[ad_1]

By: John Elliott

Narendra Modi and Mukesh Ambani do not often face mass protests. The Indian prime minister has sailed through most of his political career with few upsets, and now enjoys mass support across the country after nearly seven years in power.

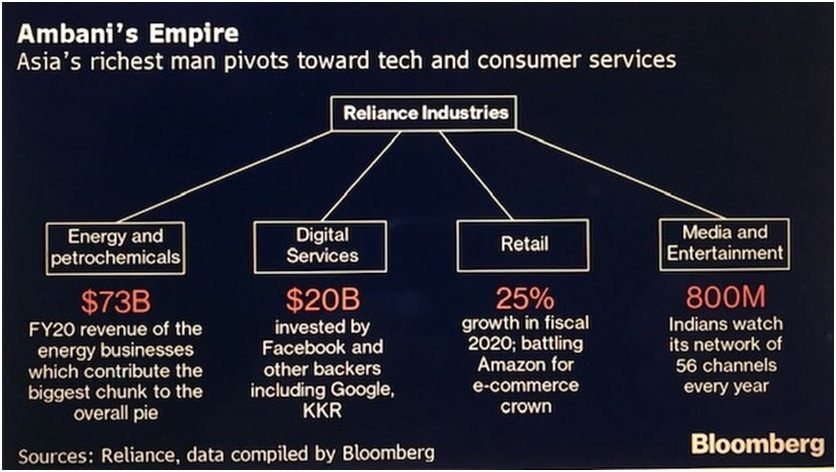

Mukesh Ambani has steamrollered through his career since he and his younger brother Anil inherited the Reliance business empire after the death of their father Dhirubhai in 2002. The brothers split in 2005 and Anil is now near bankruptcy, but Mukesh is one of the richest men in the world, wooed by international corporations for a share in his Reliance Industries (RIL) ventures.

Yet both Modi and Mukesh Ambani have been challenged by India’s protesting farmers, tens of thousands of whom have been camped for more than eight weeks on the edges of Delhi, blocking highways into the city. (Last January, there were several weeks of mass demonstrations in central Delhi over citizenship laws regarded as anti-Muslim, but the farmers’ protests are bigger, more focused and entrenched, and more disruptive.)

Farmers Demand Reform Laws Repeal

The demand is the repeal of three agricultural reform laws that were introduced last September with little consultation or serious parliamentary debate, curtailed by the pandemic restrictions. The government has held nine unsuccessful rounds of talks with farmers’ leaders – the tenth is tomorrow (January 20) – but is refusing to repeal the laws.

Impatient with the deadlock, India’s supreme court intervened last month. It unilaterally suspended the laws and set up a panel (which meets today) to find a solution. The government may have seen this as a way out of the impasse, but the farmers’ leaders have rejected the initiative and are becoming increasingly embedded on the Delhi highways with canteens, schools, entertainment, and support from their families. They plan a massive tractor rally into Delhi to coincide with the annual Republic Day parade on January 26.

The primary fear is that the laws unscramble long-established government-based trading systems for farm produce, including minimum price limits, and could lead to all-powerful oligarchic private sector corporations, like Reliance, gaining commercial clout over mostly small farmers.

A farmer prays to mark the birth anniversary of Guru Nanak Dev, founder of Sikh faith, during the protests – photo REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui

This links up with accusations that the Modi government favors large businesses, especially Ambani and Gautam Adani, who heads the rapidly growing Adani group with activities that embrace agriculture. Like Modi, both businessmen’s families come from Gujarat and both are seen as a challenge by the farmers, especially Ambani who combines being India’s biggest retailer with a growing telecom-based e-commerce business.

Cables Attacked

Power and telecom cables linking 1,500 towers carrying Ambani’s market-conquering Jio telecom services were cut earlier this month in Punjab, the state at the center of the protests where Sikh farmers are providing the movement’s backbone. Sikhs have an admired sense of community (with international links) that is lacking in many other areas and they do not subscribe to Modi’s Hindu nationalist agenda that thrives elsewhere in north India.

The Crony Raj

The Jio vandalizing is significant because it amounts to a direct attack on the alleged Modi crony raj. Protests have also hit Ambani’s Reliance Retail, which has had half its 100 Punjab stores shut since October, when protests began in the state. A 50,000 sq ft Walmart store – another symbol of big business – has been closed by pickets. “We are scared of the protesting farmers,” a senior Reliance Retail official told Reuters.

The Ambani family has been close to governments since the late 1970s and their influence on decision-making, ranging from trade quotas and customs duties to the formation of governments, has been widely reported. In the early years, this helped to build a textiles-to-petrochemicals, oil refining-and-exploration empire.

Ambani’s father stayed as far away as possible from consumers, preferring proximity to governments and the public sector, but Mukesh has branched out into retail and telecom. More recently there has been a series of telecom policies that have hit Jio’s rivals since the service was launched in 2016 with unprecedented low prices and special introductory offers.

Gautam Adani with Narendra Modi

Adani’s fortunes have escalated since Modi became chief minister of Gujarat in the early 2000s when he reportedly provided facilities and support. The most audacious success came in 2018 when rules for privatizing six airports were relaxed so that companies with no aviation experience could bid. That suited the inexperienced Adani who won the six bids and has now taken control of Mumbai airport, making him a leading operator. He is also India’s biggest operator of private ports and is significant in thermal power generation, power transmission and gas distribution.

There are plans for US$6 billion worth of solar plants. A massive US$30 billion of bonds and debt (according to Dealogic) does not seem to deter investors. Total France yesterday announced a US$2.5 billion investment in Adani Green Energy, which will include a role in solar power transmission.

That pales beside the US$27 billion that Ambani has secured in the past year, belying foreign investors’ earlier wariness about linking up with the reputedly tough tycoon. The investments are in Jio and include US$5.7 billion from Facebook for on-line grocery delivery and US$4.5 billion from Google with planned development of a smartphone.

After a shaky start when supermarkets began appearing in India in the early-mid 2000s and protestors attacked some of his first Reliance Fresh stores, Ambani has become India’s biggest retailer.

This corporate clout originally worried small kirana stores and now worries the farmers, especially in Punjab and neighboring Haryana where an existing government-run mandi (local markets) system is strongest. The private sector can buy direct in many areas of the country but the farmers fear that Reliance and others will drive down prices and maybe enter contract farming. There is also a fear in other parts of the country – illustrated by sugar cane farmers in Uttar Pradesh – that the government’s price support for produce might end.

Reliance insists it has never done corporate farming and has no plans to do so, nor has Reliance Retail “entered into long-term procurement contracts to gain unfair advantage over farmers or sought that its suppliers buy from farmers at less than remunerative prices, nor will it ever do so.” That of course is open to interpretation and, unsurprisingly, failed to impress the farmers, even when Reliance said it believed in “building a strong and equal partnership” with farmers.

More than half India’s 1.4 billion people live in rural areas and are linked to agriculture, which needs far wider reforms than the government’s proposed new laws. Once renowned as the grain and food bowl of India, the plains of Punjab and Haryana have been over-farmed for decades, depleting water supplies and the quality of the soil. That is fueling the farmers’ frustrations and needs to be addressed along with other measures to boost productivity, develop farm-to-shop supply chains and curb widespread wastage.

The government should clearly address these wider concerns, not just focus on controversial legal initiatives. Eventually, the protests will end, but the government might come to regret allowing the dissent to fester. In the Punjab, the resentment against big business, and Modi’s involvement, will only grow.

John Elliott is Asia Sentinel’s South Asia correspondent. He blogs at Riding the Elephant.

This article is among the stories we choose to make widely available. If you wish to get the full Asia Sentinel experience and access more exclusive content, please do subscribe to us.

[ad_2]

Source link