[ad_1]

After watching a homeless man beat up his girlfriend, Claudia Parola had had it.

She was fed up with the drugs being dealt outside the studio where she does pottery in Silver Lake and witnessing the struggles of people living on the streets of city she has called home for a decade. So she dashed off a note to Sen. Dianne Feinstein describing the situation and asking what she was doing to fix California’s crises of homelessness and a lack of affordable housing.

For Parola, the response was less than satisfying. In fact it was infuriating.

“The issue you described appears to be one that can only be resolved by your local public officials,” read the response from Feinstein’s office. “As a United States Senator, I do not have jurisdiction over municipal and county governments or the actions of non-federal agencies.”

In the most literal sense, that was true. Still, the federal government — with all its financial and bureaucratic might — plays a central role in how local communities deal with affordable housing and homelessness. A spokesman for Feinstein didn’t respond to a request for comment.

President Trump used the sight of tents in San Francisco and Los Angeles as a political cudgel to batter cities run by Democrats. But despite some stimulus money that paid for shelter and some behind-the-scenes talk intended to lead to wider solutions, the Trump administration offered little in the way of new homelessness policies.

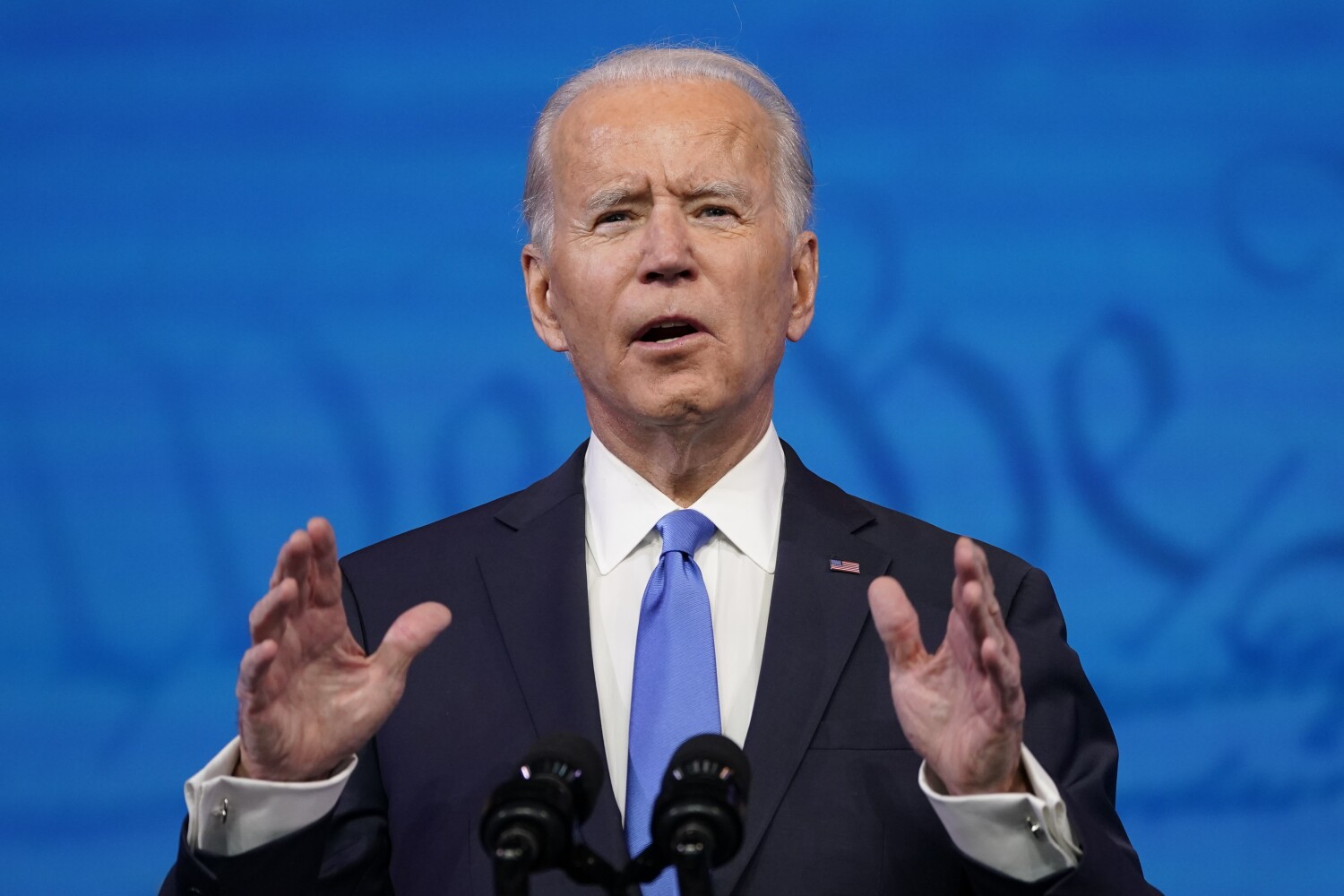

The new Biden administration is offering to spend more on the problem — but it will need buy-in from Congress.

The last available data show over 65,000 homeless people in Los Angeles County and more than 150,000 in California overall. Experts and public officials all expect homelessness to increase as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

President Biden’s proposals for another round of pandemic stimulus spending include billions that would help people on the streets — and those in danger of winding up there.

Shortly after taking the oath of office, the new president signed an executive order asking the Centers for Disease Control to extend an eviction moratorium through the end of March.

Biden wants Congress to pass another $25 billion for rental assistance, an extension of eviction and foreclosure moratoriums until September 2021 and $5 billion for municipalities to buy hotels and motels so that they’re not as reliant on large shelters, which have been places where coronavirus spreads rapidly. The state used one-time federal funding last year to great effect, spending $750 million to purchase nearly 6,000 hotel, motel and apartment units.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget includes another $750 million to buy more hotel, motel and apartment units. Paired with the money in Biden’s proposal, it could have a significant impact.

Biden’s housing plan, which was released during the campaign, has been lauded by some housing experts, who say it could go a long way toward quelling homelessness. Perhaps most significant, he has called for making Housing Choice vouchers—known to many as Section 8 vouchers — available to anyone who qualifies for them. The underfunding of the program means that millions of people who qualify for the rental assistance don’t receive it.

Biden also supports a bill, introduced by Rep. Maxine Waters, that would vastly expand grant programs for homelessness through HUD.

“We have a tremendous opportunity ahead with President Biden, having run on a commitment of housing as a human right, and putting out his intention to make housing assistance universally available to everybody who needs it,” said Diane Yentel, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. She was considered by Biden for secretary of Housing and Urban Development before he chose Rep. Marcia Fudge (D-Ohio). Fudge declined an interview request for this article.

“That’s what that people who are homeless in L.A. and everywhere need most — access to affordable housing,” Yentel added. “So I do think that it’s a big vision, and there’s a possibility of realizing it. It’s not just a lofty goal. it’s achievable.”

Yentel and others said that the Biden administration will have a lot of work simply re-staffing HUD and using the rule-making process to undo much of what the Trump administration enacted. They cited Trump’s repeal of rules put in place by President Obama that required municipalities to document racial bias in communities in order to receive funding from HUD.

Additionally, some former HUD officials and housing advocates would like to see the repeal of rules like one that excluded families with mixed immigration status from public housing and rental assistance. Local officials have said that nearly 11,000 people in the city could be evicted if the rule remains in force.

During the Trump presidency, the White House proposed drastic cuts to homelessness funding in HUD budgets, although the cuts never survived congressional review. Still, there is evidence that HUD Secretary Ben Carson did seek solutions to homelessness in Los Angeles specifically.

A Carson visit to skid row in September 2019 sparked months of negotiations between the him and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and their staffs.

Trump officials toured the city, visiting a building in Hawthorne that might be turned into homeless housing and asking local officials how more policing could help reduce the proliferation of tents on Los Angeles’ streets..

Both Garcetti and Carson declined to speak to The Times for this story, but the discussions were serious enough that draft agreements were shared between the sides. They centered on diverting roughly $300 million in unspent HUD grants to Los Angeles, according to documents and half a dozen officials involved in the talks, all of whom asked to remain anonymous in order to speak candidly.

Still, local officials never got a clear sense of exactly how much was being offered because federal law dictates that recaptured HUD money must to go through a competitive bidding process and couldn’t simply be gifted to Los Angeles. And they were uncomfortable with strings attached to the money. For instance, HUD officials wanted to designate certain areas as “safe-sleep zones,” according to one person involved in the talks, while giving police permission to move people who were sleeping in other areas of the city.

In one form, the deal called for the construction of 1,000 interim shelter beds on local and federal land, including the permanent use of the West L.A. Armory as a homeless shelter. The U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps would have offered medical services for people on the street. Additionally, the Department of Justice was expected to give a $400,000 grant to local law enforcement.

The talks dragged on until March 2020, when the worsening pandemic diverted attention and resources to other pressing needs.

“It was probably 75% incompetence, 25% pandemic that led to this not happening,” said one person involved in the talks. “Garcetti and Ben Carson were like, just pals. They were friendly, and it was genuine and Garcetti just found redeeming qualities in the secretary, that I think not many other folks were able to find.”

Matt Schwartz, the CEO of the California Housing Partnership, said the first six months of the Biden administration will be about making sure the money that’s already been appropriated gets out the door efficiently and to the people most in need.

He added that the pandemic’s effect on real estate and the large amounts of money available through relief bills present a golden opportunity to continue buying buildings to house homeless people. He applauded a Biden proposal to create a new tax credit of up to $15,000 for first-time home buyers as well.

For Faizah Malik, senior staff attorney for community development at Public Counsel, that money could be best spent following through on the demands of activists in Los Angeles to “cancel” rent. The plan Malik and her colleagues put together revolves around clearing the back rent owed by Angelenos hurt by the pandemic and then having landlords apply to the county for assistance.

That would be funded using the $2.6 billion California received in the last stimulus package, and the city and county could combine the $600 million Malik estimated they would receive. Small landlords and nonprofit affordable housing providers would be given priority access to these funds. Although other estimates are far higher, the state Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates California renters who have experienced some amount of unemployment since March owe $400 million in unpaid rent, and Malik says that the proposal she supports could be used again if more rental assistance is passed by Congress.

“I think that they have the financial resources that could really help make a big difference in L.A.,” Malik said of the federal government.

“At the local level, we’re dependent on the state and federal government. We need to build more affordable housing and there’s just not enough funding. I think that’s definitely an area where the federal government can help address homelessness — through programs for supportive housing.”

[ad_2]

Source link