[ad_1]

There were essentially two parts to Intel’s fourth-quarter 2020 earnings call on Thursday: the actual results, and the homecoming of former Intel CTO Pat Gelsinger as the company’s incoming chief executive.

Gelsinger, who doesn’t officially return until February 15, was invited to sit virtually alongside outgoing chief executive Bob Swan. Though Swan shepherded the call, Gelsinger contributed frequently, including outlining his vision for what he hoped to achieve at Intel. Gelsinger has his eyes fixed on 2023, when it sounds like Intel plans to reboot its manufacturing leadership on the next-gen 7nm process.

What we don’t know, of course, is what Intel plans to do until then. Gelsinger asked to be allowed time to join the company, receive a detailed briefing, then publicly outline his plans sometime afterward. Until that time, Gelsinger is otherwise free to enjoy his “come to Jesus” moment, and he took advantage of it.

“This is a great company, and one that I have great history with,” Gelsinger, a 30-year veteran of Intel, told analysts. “Grove, Moore, Noyce: the people that I grew up with, at their feet, learning.”

Returning to the days of ‘Intel Inside’

Gelsinger’s goals for Intel are fourfold, he said: to design and build great products, by itself and in conjunction with its partners; to become more agile; execute, so that customers can rebuild their confidence in Intel and its supply chain; and to restore the company’s culture. “We will have the Grovian, maniacal execution, data-driven culture—and rebuilding that as part of this company,” Gelsinger said.

By now, Intel’s manufacturing struggles are well known. As Intel’s legendary “tick-tock” manufacturing model slowed, its CPUs got stuck at 14nm. Intel released seemingly endless generations, with maddeningly incremental improvements, giving competitors ample time to catch up.

Intel is now trying to move its processors to the 10nm mode, which can offer power and frequency advantages. The company’s Tiger Lake mobile chips are 10nm parts, but the just-announced Rocket Lake-S desktop parts are not. Intel is also weighing outsourcing more of its microprocessor manufacturing, which might have implications for both price and performance.

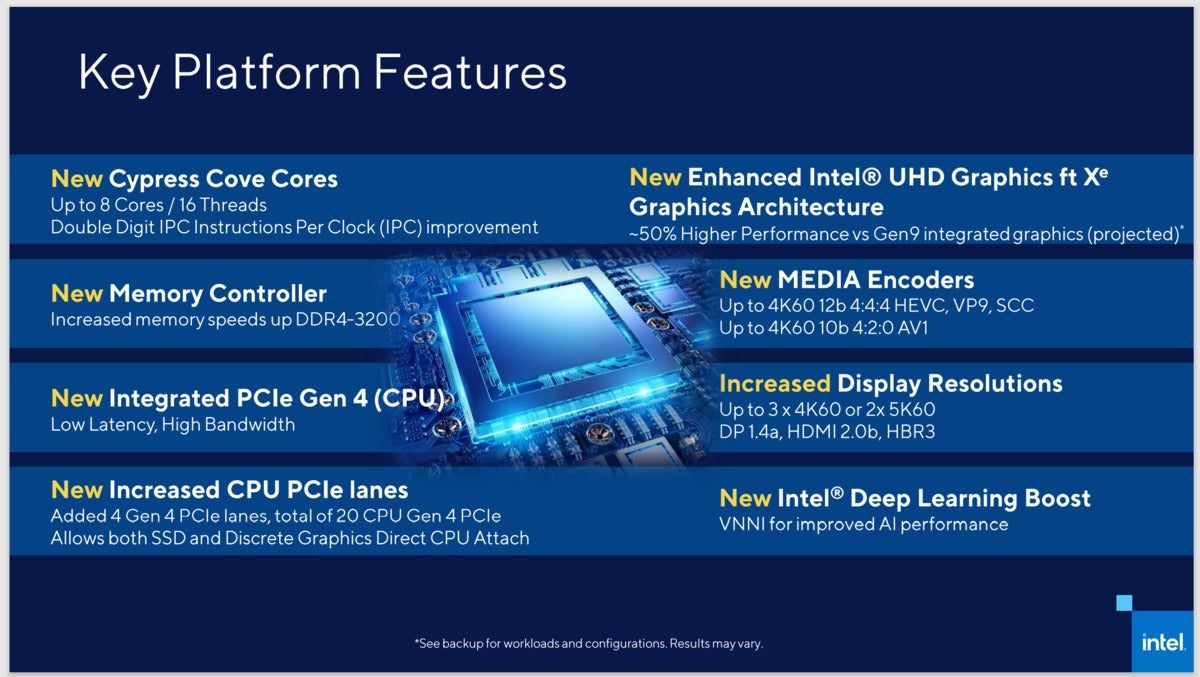

Intel

Intel Intel’s Rocket Lake architecture.

Gelsinger didn’t offer any specifics on those decisions, because he still isn’t formally an Intel employee yet. He was free, however, to speak boldly about what he hoped to accomplish. “Clearly, we’re not interested in just closing any gaps [with external foundries], we’re interested in resuming that position of the unquestioned leader on process technology,” Gelsinger told analysts. Gelsinger later said the majority of Intel’s 2023 products would still be manufactured internally. “We’ll provide more details on this, and our 2023 roadmap, once I fully assess the analysis that has been done, and the best path forward,” Gelsinger said.

Gelsinger also announced a more tangible prize: luring back a key chip designer to Intel. Gelsinger told analysts that he helped entice Intel “Nehalem” architect Glenn Hinton out of retirement. “You’ll see other announcements of key leaders coming back in,” Gelsinger added.

Finally, Gelsinger said that it was important for Intel to be healthy, as a “national asset” for both the United States and its technology industry. Swan also said that Intel would be willing to serve as a foundry partner for the U.S. government, if asked.

Refocusing on 2023?

Beyond that, the future still looks foggy. Analysts pointed out that whatever Hinton planned to work on would require a few years to produce—which would get us to about 2023, anyway. Gelsinger and even Swan didn’t really touch upon the 10nm transition at all. Swan noted that Intel’s 14nm SuperFin technology was now up and running at three high-volume fabs, and that supply of 10nm products was up four times more than the previous year. Swan added that Intel has refined its 7nm process technology, smoothing out the steps that led to defects in the manufacturing process, and delays in production.

“I think he’s [Gelsinger] setting expectations low and buying himself some time,” Pat Moorhead, principal analyst at Moor Insights, said via an instant message. “The next two years are all about internal 10nm [production] and external foundries.”

For that matter, Gelsinger backed up Swan’s earlier statement that Intel was considering bringing in outside foundry equipment into Intel. Intel was committed to “innovation that has leading the industry on a consistent basis,” Gelsinger said, and “sometimes that is something that happens outside the company.”

Intel: A supplier of cheap chips?

Intel’s earnings numbers, unexpectedly released before the call, painted an interesting picture of Intel’s chip trajectory. PC volumes grew by 33 percent, and notebook revenue soared by 30 percent—but the average selling price of those notebooks dropped by 15 percent. Intel executives said that they expect PC demand to continue into the first quarter, primarily weighted by what they call “small core” devices. That’s Intel-speak for cheap chips, what Intel chief financial officer George Davis said were sales weighted into the Chromebook and education space. As Davis noted, this was a market that Intel couldn’t sell into during much of 2019 and 2020, when processor shortages caused the company to focus on selling premium chips.

With more capacity on hand, Intel can “make it up on volume”—the same strategy that DRAM vendors or other commodity vendors use with products that offer a slim profit margin. AMD is doing much the same thing in the face of limited manufacturing capacity, carving out a niche with high-end, expensive processors, Moorhead noted.

Gelsinger’s likely goal, then, may to be resolve Intel’s manufacturing problems and design premium, high-performance chips. If that sounds familiar, well, you’ve probably been following Intel for a while—back when Gelsinger worked for the company in the late 1990s. Will Gelsinger be able to bring back the good old days? The next few years will tell.

Updated at 11:07 AM on Jan. 22 with additional detail.

[ad_2]

Source link