[ad_1]

By: David Brown

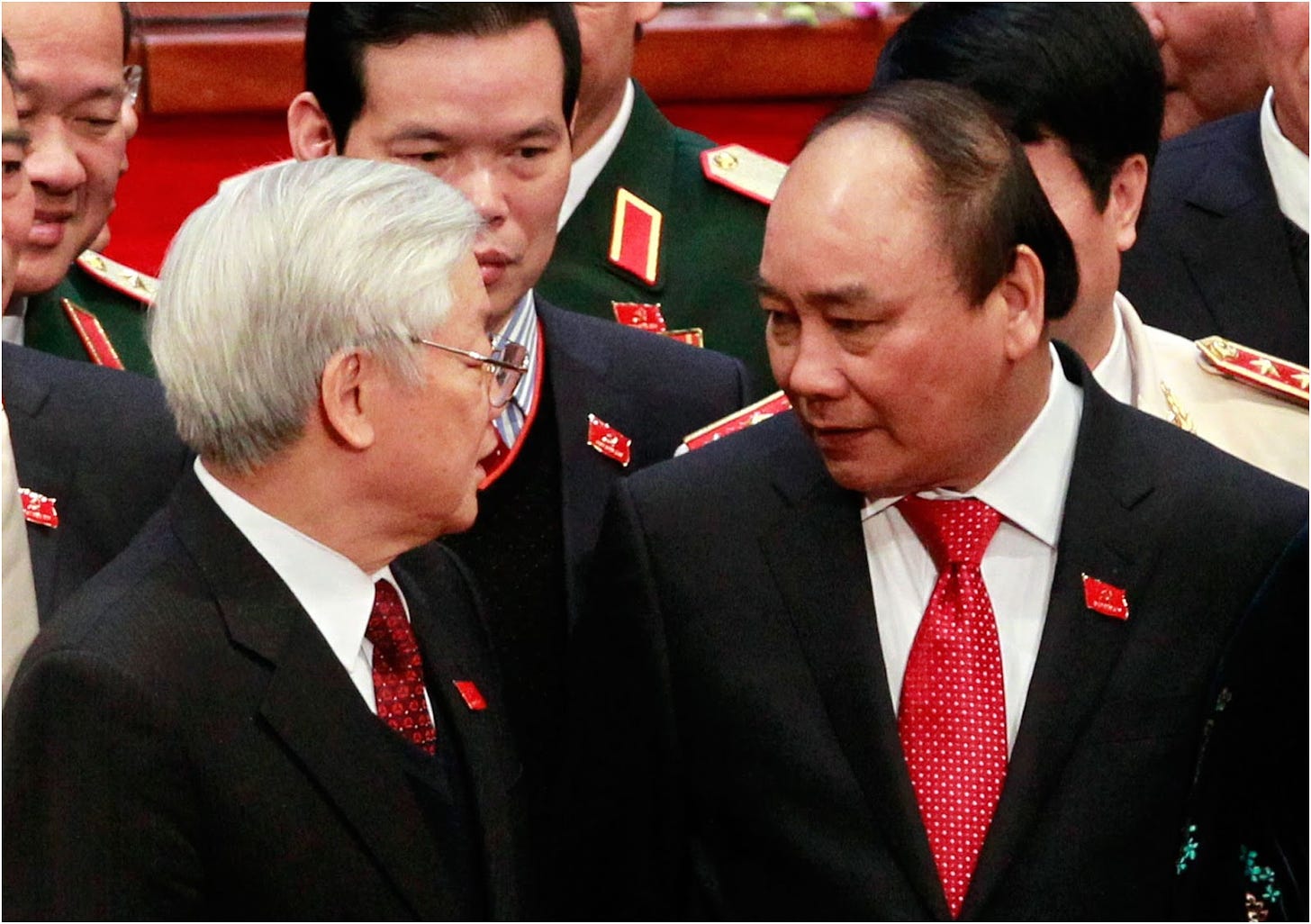

By all indications, Nguyen Phu Trong (above, left, with Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc) is sure that what’s good for the Communist Party is good for Vietnam. That explains why, instead of going gracefully into retirement, the now wobbly, still wily 77-year-old has connived to get himself a third term as the party’s general secretary.

Trong has had some successors in mind. His favorite was Dinh The Huynh, a propaganda specialist who toiled by Trong’s side for most of his career. However, Huynh was granted a leave of absence from the party’s politburo early in 2018 “to continue his recovery from a long illness.” Then there was Tran Quoc Vuong, Trong’s deputy in his campaign to cleanse the nation and the party of corrupt elements. Vuong seems to have made more enemies than friends in that role. It’s said that when the party’s central committee took a straw vote in October, Vuong’s approval rating was remarkably low. Rumor has it that he trailed far behind both Nguyen Xuan Phuc, the incumbent prime minister, and Ms. Nguyen Thi Kim Ngan, chairman of the National Assembly.

Phuc had set his sights on replacing Trong in the party’s top office. He is said to have picked up broad support from the party’s “government faction,” particularly among officials from Vietnam’s central and southern provinces and, significantly, from business circles that appreciated his far-sighted, steady, and largely scandal-free direction of Vietnam’s government.

Ah, but could the always-smiling prime minister be trusted to continue Trong’s agenda? That was the problem. Maybe he’d be a bit soft on corrupted colleagues. Maybe he’d tell the national police to be less zealous in rounding up citizens caught saying mean things about the party. And perhaps Phuc would wink at self-evolution.

From the perspective of a doctrinaire ideologist, there’s nothing worse than self-evolution. It describes members who decide that Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh thought don’t provide all the answers, who fall prey to the dangerous notion that the party could constructively experiment with pluralism or make more room for civil society. It’s a label for members who don’t acknowledge the “inevitable constraints in the implementation of the market economy, open-door policy and international integration.”

It seems obvious that Vietnam, dirt-poor 30 years ago, wouldn’t have become a middle-income country (with per capita income of US $3,500) without a lot of self-evolution going on. But apparently, there are still a bunch of apparatchiks at the party central office who really do believe self-evolution will destroy the party…er, the country.

Just the suspicion that Phuc and his colleagues in the government faction might be squishy on self-evolution seems to have convinced Trong to unwrite the party rules he’d himself devised to sideline Phuc, now 67, and make Vuong’s election inevitable. By persuading a majority of the central committee to drop a rule that no more than one person over the age of 65 could remain on the Politburo and to finesse another rule barring someone from holding the same post more than twice, Trong regained the whip hand. After a central committee meeting convened on January 15, just a week before the 13th Party Congress was scheduled to begin, the rumor mill reported with rare unanimity that Trong will again be general secretary.

Phuc’s consolation prize is said to be the largely ceremonial role of state president.

Trong reportedly has also advanced another stalwart of the party faction, Pham Minh Chinh, as the prime minister-apparent. Chinh is a former police general who since 2016 has headed the party’s organization department, a role rich with opportunities to collect IOUs.

The prime minister has been expected to go to Vuong Dinh Hue, who has served with distinction as finance minister (under Dung) and deputy prime minister (under Phuc). Instead, Hue seems slated to preside over the National Assembly, another role with more prestige than substance.

With these four positions set, if that’s indeed the case, an intraparty activity now focuses on selecting roughly 100 successors to central committee members who are ‘timing out’ after two terms, and to filling empty seats on the party’s politburo (executive committee), which will have 17 to 19 members including Trong, Phuc, Chinh and Hue, and manage party affairs from day to day. Campaigning will be low-key, off-stage, and intense nearly to the last day of the congress on February 2, when all these appointments to the party leadership will be announced.

Trong’s painfully-constructed scenario could yet be blown away. The elevation of Chinh and the retention of Trong at the expense of Hue and Phuc has the practical effect of subordinating the party’s government faction. That and the coincidentally reduced representation of cadre from the southern half of the country in top echelons are said to be broadly unpopular.

Allies of Phuc and Hue might protest their relegation either by urging the central committee to reconsider its reported compromises or by demanding that the matter be referred to the entire party congress. In extremis, the previous prime minister, Nguyen Tan Dung, tried something of this sort at the 12th Congress in 2016; he didn’t get far. Although Phuc’s a far more worthy candidate, neither will he, most likely.

David Brown is a former US diplomat with wide experience in Vietnam and a longtime contributor to Asia Sentinel

This article is among the stories we choose to make widely available. If you wish to get the full Asia Sentinel experience and access more exclusive content, please do subscribe to us.

[ad_2]

Source link