[ad_1]

North Korea and its nuclear weapons program are often analyzed through the lens of hard power — the power of coercion, achieved through military, technological, or economic force. Such analysis is important, but it’s incomplete.

When North Korea conducts large, publicized demonstrations of its military capabilities — for example, the October 2020 and January 2021 military parades — how and why these capabilities are portrayed are just as important as what they represent. From the opening shots of these events, it was clear that they were not just technical displays of military systems. Instead, they represented a large-scale exercise in aesthetic composition designed to support Pyongyang’s strategic objectives. North Korea’s leadership instrumentalized the aesthetic presentation of its military systems in order to bolster its nuclear and conventional deterrent, consolidate the leadership’s domestic political power, and send a message about Kim Jong Un’s posture and policy for the next American administration.

From Aesthetics, Deterrence

Throughout history, totalitarian regimes have wielded art and aesthetics as tools to help achieve the goals of the state. (For an overview of the role of art in North Korea, see Jane Portal’s work.) Although closely linked, art and aesthetics are distinct in a way that is meaningful for understanding North Korea’s pursuit of deterrence. The term artistic references art itself, either its creation or the representative qualities of a finished product. But aesthetic describes how artistic choices are perceived and experienced by a viewer. Van Gogh’s thick brushstrokes make a viewer perceive three-dimensionality or movement in a painting, while Picasso’s Blue Period color palette may elicit feelings of sadness or sympathy.

Pyongyang’s recent parades, convened to commemorate major Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) events, were less of a nuts-and-bolts showcase for North Korean military capabilities and more of a performance, carefully designed to elicit aesthetic reactions from specific internal and external audiences.

But given North Korea’s limited resources and other, more pressing problems to address, why would it invest in such elaborate, seemingly symbolic performances, instead of a bare-bones demonstration of its capabilities? And why should external audiences pay attention to North Korea’s aesthetic choices when their advancements in military technology — demonstrated memorably over remarkable missile and nuclear weapon testing campaigns in recent years — seem far more consequential?

The answers to these questions are tied up in what Pyongyang may perceive to be the requirements for nuclear deterrence. In its purest sense, deterrence hinges on two key components: capability and belief. In order to successfully deter adversaries, a state must have the technical capabilities to execute its threat. This half of the equation lives in the world of the rational, which can be calculated, measured, or tested.

But the other necessary component for deterrence is belief. Adversaries must believe that the state will follow through with what it threatens, or at least believe that it would be too risky or costly to call the state’s bluff. This half of the equation is less measurable, more art than science. Beliefs emerge as a result of perception, making their genesis subjective, ever-shifting, and sometimes removed from the world of facts or logic.

Aesthetic choices, in their ability to shape perception, can weigh on deterrent messaging in certain contexts. In contrast with the bluntness of technical showmanship, aesthetics exert influence in a way that is fluid and often unseen. They operate in the realm of emotion, quietly eliciting fear or love at a subconscious level. Pyongyang’s aesthetic choices make three important contributions to North Korea’s deterrence needs.

From the Darkness, Light

The old adage, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” is tired and clichéd, but here it rings true. North Korea’s aesthetic choices — be it at a parade or in general propaganda — allow for a great deal of information to be packed into a single image or performance.

Perhaps the most striking aesthetic choice of both parades was their nighttime setting. Given the challenges and costs associated with staging an event in the dark — especially in a country with rampant power outages — the decision to hold the parades at night was not made haphazardly.

Rodong Sinmun

Take this official state photograph from the October parade as an example (although it’s worth noting that much of the footage from the January parade bears striking resemblance to its October counterpart).

Kim Il Sung Square, the setting for both parades, is lit up blindingly bright in the lower third of the photo. Spotlights cast across the Taedong River to Juche Tower, symbolically connecting the parade to the legacy of juche — loosely translated as “self-reliance,” a North Korean philosophy that emphasizes ideological autonomy, economic self-sufficiency, and military independence from imperial influence. The flame at the top of the tower is eternal, placed in a sky crowded with celebration. In this photograph, the entire North Korean politico-military project is not only washed in light; it is a source of it. It shines bright in an otherwise dark and starless night.

This imagery harkens back to an important photograph from December 2019, one that helps contextualize the aesthetic message of the recent parades. In the photo below, Kim Jong Un, his spouse, and his closest military advisers huddle around a bonfire atop Mount Paektu. Typically, visits here indicate a major shift in policy to come. As the symbolic birthplace of the first Korean kingdom (and Kim Jong Il) and a historical center of resistance to foreign occupation, Mount Paektu is a geographical embodiment of juche, a reminder of the sacrifices made for the state’s self-reliance and independence.

KCNA

This photograph came after a tumultuous year for Kim’s relationship with the United States. After the failed Hanoi Summit in February 2019, Kim shifted from negotiation to resistance, urging his domestic audience to tighten their belts in preparation for a dark period ahead. The bonfire photos were released shortly before a key WPK meeting at which Kim announced that North Korea would no longer be “unilaterally bound” to any long-range missile and nuclear test moratorium and would be pursuing a “new strategic weapon” — presumably the ICBM debuted at the October 2020 parade — in the year ahead.

The parallels here are striking. After another long year without a negotiated settlement — not to mention natural disasters and a global pandemic — the present moment in North Korea likely feels like a dark night, indeed. The nighttime setting of both parades suggests a continuation of Kim’s resistance, seen in his disillusionment toward prospects for negotiation and his continued reliance on military strength. But like Kim’s tending the bonfire atop Mount Paektu, the parades’ aesthetic choices emphasize a longstanding, foundational myth at the heart of the Kim dynasty’s message to its people: the leaders are a guiding light, a force for good and safety, the sole protectors of the North Korean people and state in an otherwise dark, chaotic, potentially hostile world.

From Choices, Contradiction

Throughout their history, military parades have been aimed at both internal and external audiences. Another reason why aesthetics are valuable in this context is because they allow a state to communicate multiple messages, often to multiple audiences, simultaneously.

Kim Jong Un often communicates his nuclear posture in speeches and press releases. Although much of the U.S. government and intelligence community pays close attention his language, many policymakers and onlookers underestimate these messages or don’t take them seriously. In part this is because such communication is a product of a tightly controlled propaganda apparatus, but also because this messaging — for instance, frequent declarations of “war” by North Korea — may feel arcane or silly compared to that of most governments. If Kim’s audience, widely conceived, doesn’t listen when he tries to communicate a crucial component of his deterrence, aesthetics offer him another way to get his point across.

The choice to include nuclear weapons in these parades sends a significant message in its own right. In pursuit of deterrence, states have multiple options to communicate their capabilities. Here, credibility of a state’s capabilities increases along a spectrum, but so do risks and costs. A speech about a weapon is low-cost, but it does little to convince an adversary that the weapon exists and functions properly. A parade requires massive financial investment, but it can provide much more concrete evidence of a state’s ability to execute its threat. A successful test of a weapon would be even more credible, but a failed test would significantly damage a state’s credibility in the future.

On its own, high-definition footage from the recent parades won’t fully convince international audiences of North Korea’s technical capabilities. However, the aesthetic framing of these capabilities can enhance the credibility of Pyongyang’s messaging. The coverage of North Korea’s newest ICBM — unnamed as of yet, but likely the Hwasong-16 — offers a rich example.

Rodong Sinmun

This image from the October parade is cropped so the Hwasong-16 fills the entire frame, removing any sense of scale. It’s made to feel enormous, spanning the length of the building in the background. The angle of the camera creates the illusion that this missile is rolling forward, almost crowd surfing, over the cheerful, flag-waving patriotism of the North Korean people. This framing was also used in January’s debut of the Pukkuksong-5, North Korea’s new SLBM. In sum, these aesthetic choices make the subtle argument that North Korea’s nuclear forces — what the country has long called a “treasured sword” — are not just an insecure dictator’s obsession, but rather a project with the full support of the people. After the 2017 test of the Hwasong-14, North Korea’s first ICBM, state media made this clear, describing the achievement as the “greatest desire of the nation.”

Although this footage emphasizes the missile’s size, it’s worth noting that even from the most confrontational angles, the nosecone isn’t aimed directly at the camera. Thus, although the viewer is certainly aware of the threat, she is not its target. This aesthetic framing allows North Korea to signal the self-proclaimed “defensive” nature of its nuclear program while ensuring that its destructive power is not lost on its audience.

Because aesthetic choices allow for multiple messages to be delivered at once, they also allow for a sort of double-speak to occur. The earlier parade offers a particularly good example of this.

In his speech, Kim adopted a relatively conciliatory tone. He avoided more abrasive language, declining to call out the United States by name for its “hostile policy” while offering “heartfelt consolation to all those around the world” dealing with COVID-19. Some of his language aimed to elicit sympathy from external audiences. Reflecting on the impact of the pandemic, economic struggles, and natural disasters, he noted, “All of these hardships are undoubtedly a heavy burden and pain for every family and every citizen in our country.”

But the aesthetic presentation of this parade sent a different message.

Rodong Sinmun

While the nuclear-capable systems photographed in the parade never directly face the camera, the conventional forces were framed to send a more threatening message. KPA forces marched in choreographed goosestep, pictured here, harkening back to George Orwell’s famous characterization. The implication here isn’t subtle. By choosing a camera angle on the ground, the viewer is faced with a threat that is neither abstract nor implicit. It’s not a theoretical someone’s skull about to be crushed — it’s yours.

This aesthetic double-speak can also be seen in the October parade’s messaging toward South Korea. Early in his speech, Kim spoke with goodwill toward his neighbors, saying, “I also send this warm wish of mine to our dear fellow countrymen in the south, and hope that … the day would come when the north and south take each other’s hand again.”

But in photographs like the one below, aesthetic messaging contradicts the official language.

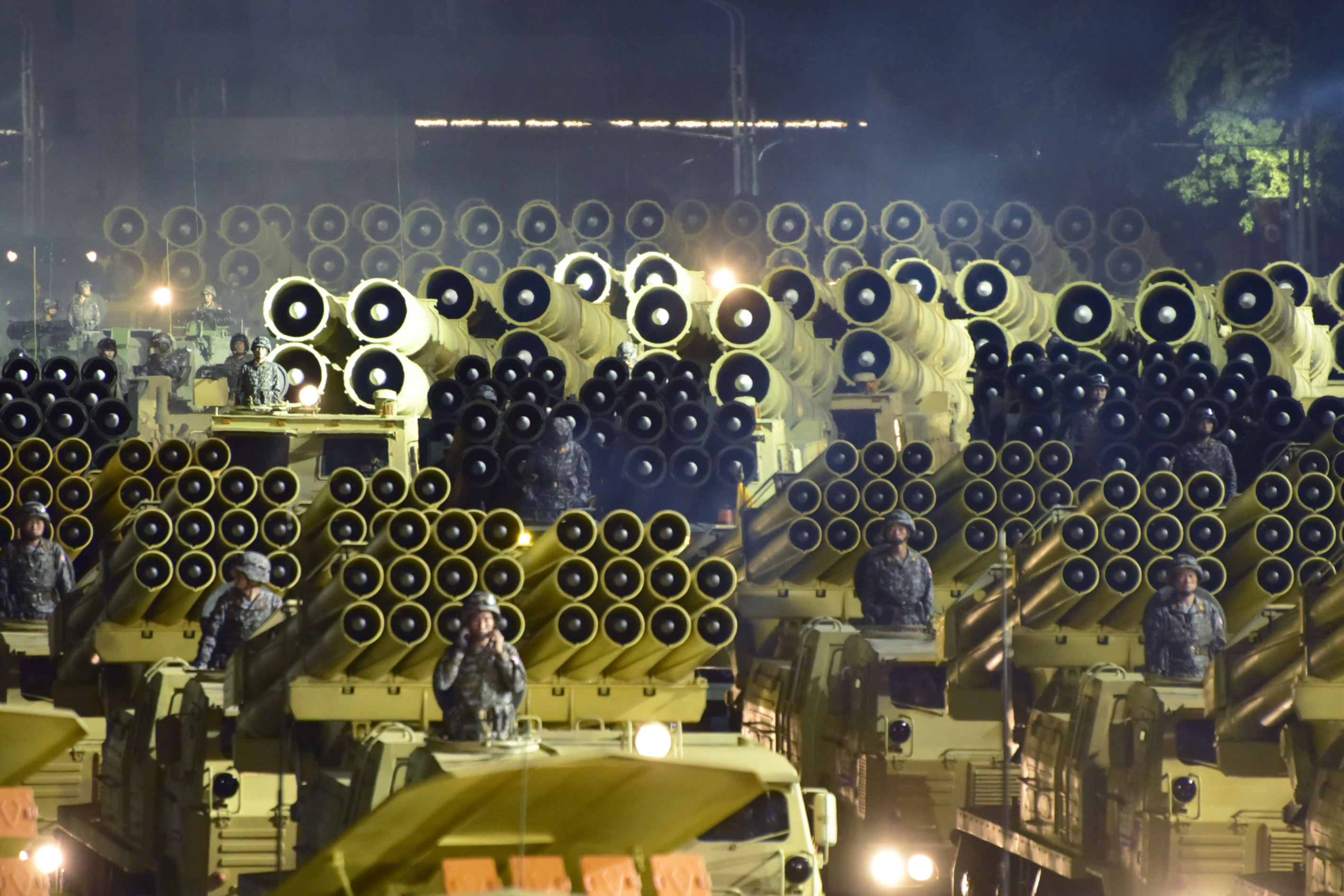

Rodong Sinmun

The MRLs, or multiple rocket launchers, pictured here are threatening to South Korea, which decided last year to pursue a new missile defense system to cope with this kind of technology. Similar to the photographs of the Hwasong-16, none of the weapons featured here are pointed directly at the camera. But this picture uses other means of visual rhetoric to elicit fear and convey a message about the skill and strength of the North Korean military. The shot is cropped so that MRLs fill the frame completely. The sheer volume of weapons, piled on in layer after subsequent layer, is overwhelming to the viewer. These layers, pointed in different directions, suggest a dynamic, adaptable defense that can be calibrated against a variety of threats. The intended effect of these aesthetic choices is to demonstrate how hopelessly expensive it would be for South Korea to build enough missile defense interceptors to neutralize this North Korean threat.

This picture creates another interesting effect. Even though the tubes are pointed in different directions, the concentric circles at the tubes’ openings repeat over and over again, creating the underlying impression of a sea of eyes — or worse, scopes — focusing on the viewer intently, watching. The aesthetics of this photograph allow Kim to make his South Korean audience aware of his threat while still maintaining plausible deniability with an amicable, well-wishing official statement.

The sum of all of these contradictions is a somewhat mixed message, and that seems to be the point. By amplifying some messages and carefully mitigating others, North Korea’s aesthetic choices allow it to maintain a careful balance between demonstrating its threatening capabilities while avoiding dangerous provocation.

From Parades, Power

Perhaps the most important aesthetic project undertaken at these parades concerns Kim’s domestic audience. Kim seeks to bolster deterrence by showing not only willingness to use his weapons, but his ability to do so based on domestic support.

Even in an authoritarian state, domestic support for a regime’s goals and behavior matter. Kim’s nuclear deterrent relies just as much on the people themselves as it does on technical capability — on people’s willingness to endure, to wait, to continue to sacrifice for the state. This relationship between ruler and subject is especially crucial in a time where the ruler has been unable to protect his citizens from so much hardship.

The medium of a parade is well-suited to communicating domestic support because it is associated with costs. Unlike a speech or KCNA article, a parade demonstrates a state’s willingness and ability to incur financial costs to send its message. But it also demonstrates the costs that the North Korean people are willing to put up — what they have already sacrificed and what they would be willing to sacrifice in the future. Put simply, you can’t eat a parade. Kim’s willingness to prioritize new military uniforms and advanced weapons systems over actual necessities for his people sends one message to an international audience. But when these choices are supported by cheering, patriotic crowds (whether or not such support is sincere), this sends another, perhaps more powerful message about North Korea’s ability to follow through with its threats.

Rodong Sinmun

KCNA

While much of the parade’s aesthetic messaging involves fear, it also devotes significant effort to communicating consensus. In photographs like the ones above, consensus is shown through unrelenting visual repetition, symmetry, and uniformity.

Oftentimes, language used to describe North Koreans relies on dehumanizing tropes. North Koreans are frequently caricatured as brainwashed, uneducated, disposable tools of the state. While critiques of these tropes are valid, it seems that, in this instance, North Korean state media is intentionally leaning into some of them in order to serve their own interests. In the above pictures, soldiers’ bodies are so precisely positioned that they become an optical pattern. In other photos, soldiers are made to look identical, even down to the angle of their jawlines. They are choreographed and photographed to appear mass-produced, as if they themselves are manufactured as weapons for the state.

Although parades alone won’t fully convince adversaries of a state’s capabilities, they are valuable for deterrence because they facilitate a mutually constitutive process through which Kim can not only express but actually build domestic support for his political goals. For members of the military, the process of putting on these parades, as one scholar put it, creates conformity in both action and thought. The shared experience of goosestepping to the tune of martial music contributes to a shared identity and a collective attachment to state ideology. This creates another, more worrisome effect. By emphasizing — fetishizing, even — its necessary defensive capabilities, a state solidifies the implicit assumption that the external world is neither neutral nor noncombatant, but threatening.

Kim’s emphasis on domestic support reveals key information about how he wants to be seen as a leader. In contrast with the dogmatic, deified personae of his father and grandfather, Kim often acknowledges his shortcomings and failures. In doing so, he portrays himself as a deeply human leader, one personally in touch with the needs of his people and, crucially, more able to cultivate their support for his sweeping plans for nuclear modernization.

From Perception, Reality

In analysis here and elsewhere, it’s impossible to say what lies in store for the U.S.-North Korean relationship — whether North Korean leaders really mean what they say, whether the United States will believe them.

As North Korea communicates its strategic capabilities in an increasingly credible manner, the technical component of its deterrence will inch closer to complete. As this happens, North Korea’s deterrence, more than ever before, will hinge on the state’s ability to influence the perceptions and beliefs of its adversaries. Accordingly, aesthetics and aestheticized demonstrations like these parades will be crucial to understanding North Korea’s intentions and behavior.

By focusing exclusively on the traditional hard power implications of North Korea’s missile systems, analysts are missing much of Pyongyang’s strategy. The aestheticization of these systems demands to be taken as seriously as the missiles themselves. As long as aesthetics are ignored, they will continue to work. They will operate quietly, unseen, aiming to influence an audience’s perception at a subconscious level to achieve the goals of the state. As long as aesthetics are dismissed as a project suited only for idealists or art classrooms, so much of how North Korea’s pursues critical state objectives, including nuclear deterrence, will be left in the dark.

Megan DuBois is the James C. Gaither junior fellow in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Nuclear Policy Program. A recent graduate of Colgate University, her research interests include North Korea, arms control, and nuclear nonproliferation.

[ad_2]

Source link