[ad_1]

Sri Lanka’s foreign debt troubles are not new and have often been juxtaposed with concerns over defaulting debt and Chinese debt trap controversies. Leading up to 2021, several rating agencies downgraded Sri Lanka’s sovereign credit ratings: Standard and Poor’s downgraded Sri Lanka’s sovereign credit ratings to CCC+/C from B-/B, Moody’s downgraded Sri Lanka’s “long-term foreign-currency issuer and senior unsecured ratings” to Caa1 from B2, while Fitch Ratings downgraded Sri Lanka’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to CCC from B. All these moves indicate concerns about Sri Lanka’s ability to fulfil foreign debt repayments. Sri Lankan government, as usual, dismissed the concerned and claimed that analysis by the rating agencies is premature and based on ill-informed models.

Sri Lanka’s foreign debt problem, which often leads to serious balance of payment (BOP) issues, is more than its massive borrowing from various foreign sources. The root causes of the ongoing crisis are found in structural weaknesses such as the contraction of trade, low tax revenue, and the lack of foreign direct investment (FDI). Failures to provide comprehensive and consistent, long-term solutions to address such weaknesses have resulted in the country running into serious BOP crises in every few years.

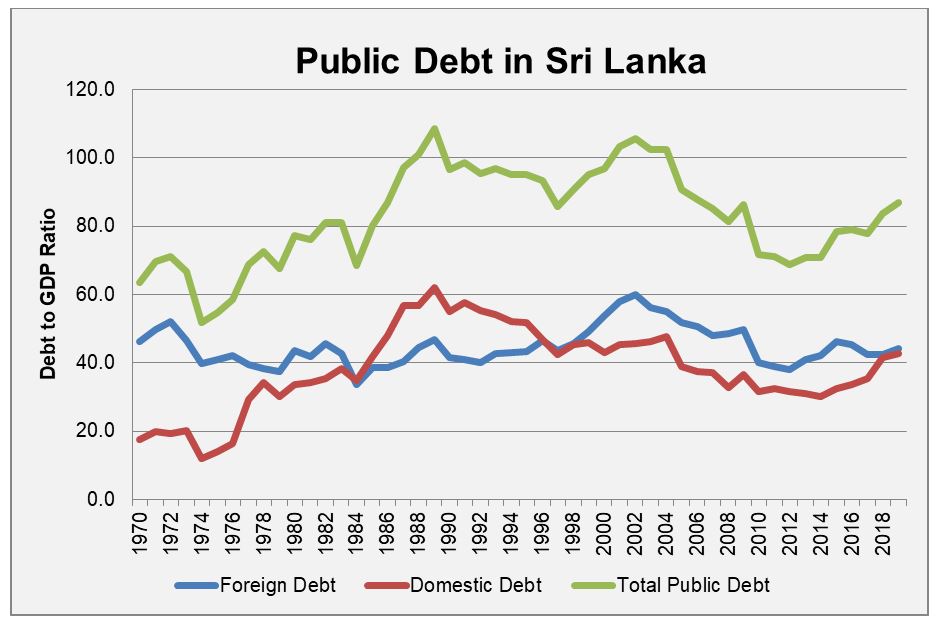

The country has been relying heavily on foreign loans for development purposes over the last four decades. Consequently, having a large foreign debt stock is not unheard of in Sri Lanka. For instance, in 1989, Sri Lanka’s foreign debt (public debt only) amounted to 62 percent of its GDP.

Data from the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

Foreign debt stock accounted for more than half of Sri Lankan GDP until 1995 and gradually continued to decline, owing mainly to rapid economic growth. As a result of the post-war economic boom, the foreign debt-to-GDP ratio dropped down to 30 percent in 2014, but growth was still driven by public debt, largely financed through foreign sources such as international sovereign bonds (ISBs) and loans obtained from China. Since 2014, foreign debt levels have been on the rise and reached 42.6 percent of GDP in 2019. This surge was a result of both Sri Lanka’s low economic growth rate and the issuance of ISBs to repay previous foreign loans obtained from 2007 to2014. During 2015-2020 ISB repayments were roughly $6.7 billion, which amounts to little over 20 percent of the current foreign debt obligations (approximately $33 billion).

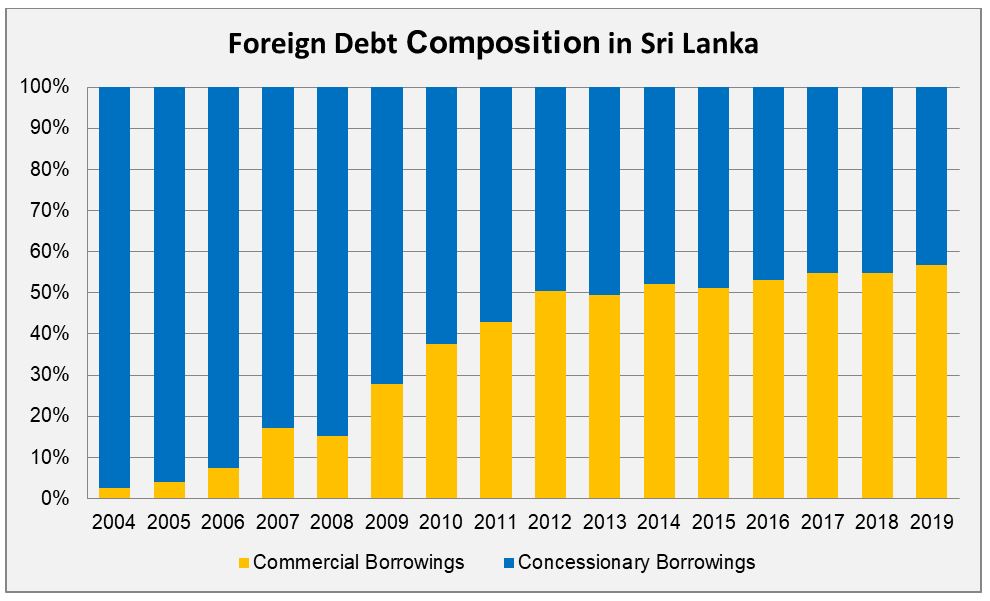

Since Sri Lanka’s foreign debt-to-GDP ratio has declined drastically compared to the figures in the early 1990s, one might ask what the current fuss is really about. The answer lies in the fact that the foreign debt dynamics of the country have taken a complete turn. During the early ‘90s, the majority of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt consisted of concessionary loans, most of which were provided by multilateral and bilateral development agencies such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Japan International Cooperation Agency. These loans had a long payback period, a considerable grace period, and were subjected to a low-interest rate. As a result of these loan conditions, which were favorable to a low-income country, the debt repayment burden was not substantial. Most of these concessionary loan repayments were distributed over 25-40 years with a low interest rate of around 1 percent or less. This meant that the foreign debt repayment burden did not pose a significant threat to foreign exchange management and Sri Lanka’s BOP.

However, the current situation of foreign debt is quite different from the situation in the ‘90s and the early 2000s. Following Sri Lanka’s upgrade to a middle-income country, its ability to access concessionary loans provided by multilateral agencies and bilateral donors declined. Sri Lanka, therefore, had to look for alternative foreign financing sources. In 2007, Sri Lanka issued its first International Sovereign Bond (ISB) worth $500 million and started raising money using international capital markets. Due to the heavy reliance on ISBs, Sri Lanka’s foreign debt composition changed completely. In 2004, commercial loans amounted to only 2.5 percent of Sri Lanka’s foreign loans, but by the end of 2019, 56 percent of the country’s foreign loans were commercial borrowings, most of which are ISBs.

Data from the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and the Department of External Resources.

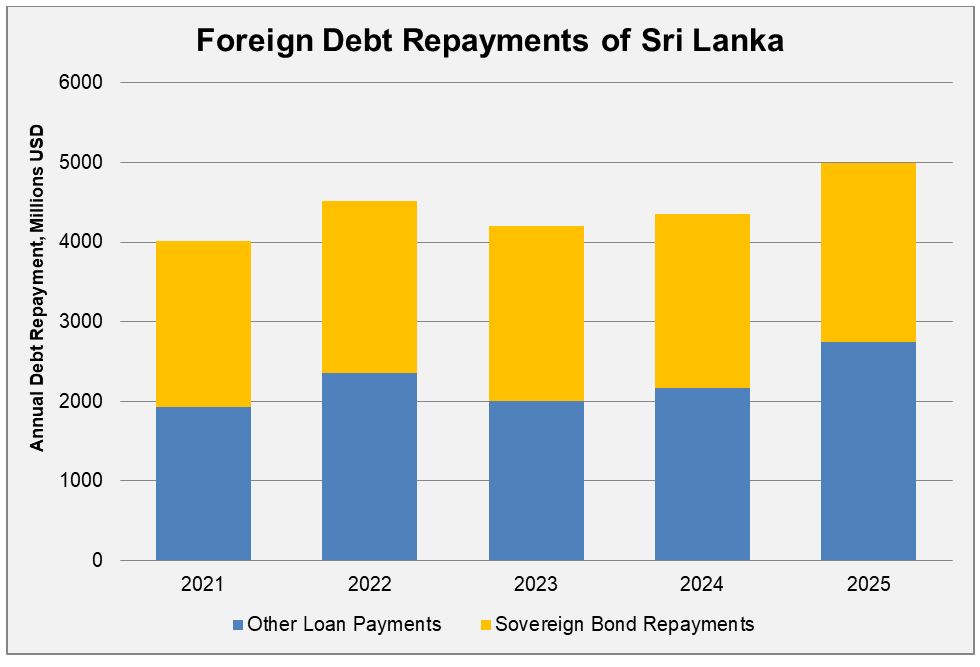

Unlike the concessionary loans, these ISBs, which are identified as commercial borrowings, have a short payback period, high interest rates, and no grace period. ISBs have a payback period of 5-10 years with an annual interest rate above 6 percent to be paid biannually. On top of that, there are principal payments – in other words the total borrowed amount of an ISB is settled at the bond maturity date, all at once, rather than being distributed over the years through annual repayments. Therefore, when an ISB matures, foreign debt repayment requirements skyrocket, resulting in a large foreign currency outflow. This leads to significant BOP vulnerabilities. Consequently, even if the foreign debt-to-GDP ratio is less than what it was two decades ago, Sri Lanka’s vulnerabilities are a lot more severe and alarming, because the debt dynamics of the country have completely shifted to a new paradigm.

Data from the Department of External Resources, Sri Lanka.

Root Causes of Debt Troubles

This change to external debt dynamics is of crucial concern for Sri Lanka, given that the country now relies heavily on commercial borrowings without addressing the structural weaknesses of the economy. Major structural weaknesses include the contraction of trade as a percentage of GDP, low levels of FDI, declining tax revenues, and a failure to diversify export destinations and sectors. As trade contracted relative to GDP – falling from roughly 33 percent in 2000 to roughly 13 percent in 2019 – export earnings have become stagnant.

On the other hand, FDI inflows remain low and successive governments gave failed to reach annual FDI targets. This meant that foreign currency inflows did not see a considerable improvement while foreign currency outflows grew due to ISB maturities and other loan repayments. This growing mismatch between forex inflows and outflows caused Sri Lanka’s foreign reserves to run dry, forcing the governments to issue still more ISBs to settle massive debt repayments. In this sense, Sri Lanka’s foreign debt problem is not merely a debt problem; it is a complicated macroeconomic and political problem including the country’s international trade and investment, which in turn shape its BOP.

Due to these unaddressed structural issues, Sri Lanka had run into BOP crises frequently over the last two decades. Most recently, the shortage of foreign currency reserves led to a BOP crisis in 2015, when the government obtained support from the IMF through an Extended Fund Facility of $1.5 billion.

Sri Lanka has resource to a few temporary fixes for its foreign debt crisis. One way was to issue ISBs and roll over foreign loans. This is costly, yet carries few or no conditions. Another option is to seek assistance from the IMF and request bail-out packages to increase the foreign currency reserves, thereby avoiding a BOP crisis. Sri Lanka has also sought financial assistance from China, largely through Foreign Currency Terms Facilities. Additionally, Sri Lanka has used currency swap facilities, largely obtained from India.

Problems in 2021

Sri Lanka’s foreign debt situation in 2021 is particularly worrying due to a few factors. Among these is the strict stance of the government that it will not use the support of the IMF. IMF support was the key to steering clear of the BOP crises encountered in both 2009 and 2015. Colombo’s insistence that it will not obtain IMF support again raises serious concerns among investors, lenders, and other economic actors over whether Sri Lanka can maintain a sufficient level of foreign currency reserves and meet foreign debt repayment obligations.

Another concern is the extreme difficulty for Sri Lanka to raise money through international capital markets (i.e., by issuing new ISBs) which was Colombo’s preferred method to settle ISB maturities in the past. With Sri Lanka’s low sovereign credit ratings and the ongoing pandemic, issuing ISBs does not seem like an easy option for the Sri Lankan government (indeed, it looks almost impossible in the near term). These two factors combined raise serious concerns regarding a potential default on debt repayments as Sri Lanka continue to struggle with possible avenues to increase foreign currency inflows.

To add to that, even existing foreign currency inflows took a heavy hit as the tourism industry came to a halt with the pandemic. Approximately 20 percent of Sri Lanka’s export income (goods and services both) is generated by the tourism industry and the adverse impact of the pandemic on the tourism industry, which is very likely to continue this year, will make it still more difficult to manage Sri Lanka’s foreign reserve position.

Thus far, the Sri Lankan government’s strategies to manage the foreign debt problem have focused on import restrictions and currency swaps. With the ongoing pandemic, the government was able to restrict the number of imports, including a halt on vehicle import, thereby reducing the foreign currency outflows. During the first 11 months of 2020, imports were reduced by $3.6 billion (a 20 percent reduction in comparison to 2019) resulting in a $1.8 billion drop in the trade deficit. This gave the government temporary breathing room to manage foreign debt repayments in 2020.

However, the reduction of foreign currency outflows to purchase fuel, largely influenced by the low oil prices in the global market and restricted travel due to lockdowns, was the largest factor in the decline of the trade deficit. During the first 11 months, fuel imports alone were reduced by $1.2 billion. Yet it is unlikely that the government will receive this boon in 2021. With the increase of oil prices in the global market in comparison to 2020 and an expected post-COVID economic revival, fuel import bills will increase again, putting further pressure on foreign reserves in 2021. The strategy of managing foreign debt through curtailing imports is not a sustainable solution for a country like Sri Lanka, for which more than half of imports are intermediary and capital goods. The continuous restriction of imports will curtail economic growth. which is not something that Sri Lanka can afford right now.

Another temporary strategy used by the Sri Lankan government is currency swaps. Sri Lanka obtained a currency swap of $400 million from Reserve Bank of India in June last year. But currency swaps are only a holding operation. This currency swap was extended for three months in November and the Central Bank of Sri Lanka settled the swap in early February. In response to this, a spokesman from the Indian High Commission in Sri Lanka pointed out that any further extension to the currency swap would require Sri Lanka having successfully negotiated a staff-level agreement for an IMF program.

The only remaining option, then, is to seek assistance from China to resolve this foreign exchange crisis. Indeed, the treasury secretary has stated that Sri Lanka expects a $1.5 billion swap facility from China. In December last year, the Treasury stated in a press release that disbursement of the second tranche of the Foreign Currency Term Financing Facility proceeds from the China Development Bank (CDB) is also expected in early 2021. It is not very clear what type of foreign currency support or loan Sri Lanka can expect to receive from China, but it is clear that Sri Lanka is betting on China to avoid a serious foreign exchange crisis.

Putting together all parts of this puzzle makes it clear that Sri Lanka’s foreign debt troubles are more likely to take a worse turn. The country is on the verge of a severe BOP crisis. The bitter reality, which the government seems content to ignore, is that these debt troubles cannot be solved using short-term fixes. The only sustainable solution lies in addressing the structural weaknesses of the economy. These troubles aren’t going to go away in a year or two either. As Sri Lanka will have outstanding sovereign bonds reaching maturity every year up to 2030, the country will have to spend a significant amount of foreign currency earnings to repay these commercial loans. That certainly is not going to be a walk in the park.

Umesh Moramudali is a lecturer at the University of Colombo focusing on public debt dynamics, political economy and economic development in Sri Lanka. He is a Chevening scholar and holds an M.Sc in Economics from the University of Warwick. The opinions and analysis presented here the author’s alone and by no means reflect the views of the institutions that the author is affiliated with.

[ad_2]

Source link