[ad_1]

Definition | How Probiotics Help | When to Take | How Long Do They Take to Work? | Signs Probiotics Are Working | Side Effects | How to Improve Gut Health | Prebiotics

“Should I take a probiotic?”

Some people say probiotic supplements are the answer to whatever ails you: digestive complaints, brain fog, immune system problems—even cancer.

And then there are those who liken probiotics to multivitamins: a surefire method of creating very expensive urine—or in this case, poop.

The truth is, taking a probiotic can be worth it.

But any potential benefits depend on factors like: Who’s taking the probiotic? Under what circumstances? And for what goal?

In fact, even though I’m a coach with a PhD in this area, most of my clients don’t take probiotics.

That’s not because they don’t ever work. It’s because we only know they work in certain situations.

That’s why in this article, I’ll guide you through:

Ready? Let’s learn all about these little bugs.

++++

What are probiotics?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), probiotics are “live microorganisms, which when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.”1

A simpler definition would be:

Probiotics are bacteria (and sometimes yeasts) that offer health benefits.

Probiotics come in supplement form and are also found in various fermented dairy products.

Fun fact: Based on the current evidence, fermented dairy, such as yogurt and kefir, is the only food that can be considered probiotic.

Other fermented foods like kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha, natto, and miso may have health benefits, but aren’t probiotic because they don’t contain the types of bacteria that fit the definition above. Also, pickled foods don’t fit the definition either (sorry!), though they’re certainly delicious.

There are dozens of strains of probiotics.

They often have long names that may seem difficult to remember and even harder to spell. I’ll mention quite a few of them in this article—not to make your head hurt, but because specific health benefits depend on specific strains.

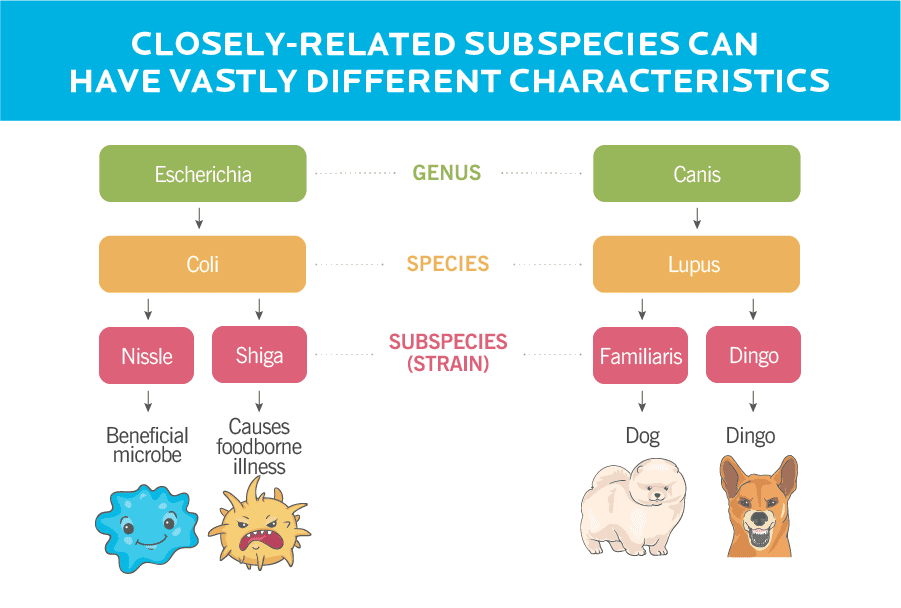

The full name of each strain includes its genus, species, subspecies (if applicable), and an alphanumeric designation that serves as an identifier.

Unless you’re a scientist, you’ll mostly hear strains referred to by just their genus and species (i.e. Lactobacillus reuteri or Bifidobacterium longum).

Occasionally, you’ll also see the specific strain included by name and/or numeric identifier.2

These distinctions can be important because, in some cases, different strains of the same genus and species have very different effects. For example, Escherichia Coli Nissle is probiotic, but Escherichia Coli Shiga (sometimes shortened to just E. Coli) is pathogenic, meaning it’ll make you sick.

To put this into real-life terms, at the genus level, we’re talking about the difference between a dog and a wolf. When we get down to the strain level, it’s like specifying between a dog and a dingo. In the chart below, you can see how the probiotic taxonomy compares to that of an animal.

For both probiotics and animals, differences at the strain or subspecies level can be more important than you might expect.

Some of the most common probiotic strains come from following genera (not to confuse you more, but genera is the plural of genus):

- Lactobacillus

- Bifidobacterium

- Saccharomyces (these ones are actually yeast!)

- Streptococcus

- Enterococcus

- Escherichia

- Bacillus

Lastly, some probiotic supplements contain multiple strains. Often, these are given a special product name, such as VSL#3, a multi-strain probiotic with Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria, and one strain of Streptococcus that you’ll learn more about later in this article.

Why are probiotics a thing?

A lot of times, people hear “bacteria” and think, ‘Oh, that’s the stuff that makes you sick.’ But our bodies are actually packed with different types of bacteria and other microbes—especially our gut.

That’s what we mean when we talk about the gut microbiome, the complex ecosystem of microbes (and their genetic material) that live in our GI tract.

These microorganisms are with us when we’re born, and they do more than just freeload. When everything’s working properly, they:

- help ferment undigested nutrients to produce beneficial compounds, in some cases (those are called postbiotics)

- prevent harmful bacteria and yeast from overpowering the gut by starving them out or actually attacking them (cool, right?!)

- play a part in regulating immune responses to infections and potential allergens

- influence energy balance and potentially body composition

- may (potentially) influence mood, behavior, and cognition.

As you can see, our GI microbes have several important and wide-ranging jobs. So it’s understandable that people want to prioritize their gut health. Thus, the interest in probiotics.

But what are we actually talking about when we use the term “gut health”?

It depends on the context. But usually, when we talk about having a healthy gut, we mean:

Having a diverse gut microbiome with a wide array of different types of microbes and microbial genes.

Diversity is crucial, because it prevents one niche group of microbes from overpowering the rest of the population, which could make you sick.

It’s also important because we know our gut microbes have key metabolic and immune functions related to their genetic material. Except… we don’t totally know which microbes do what.

So a wider variety of microbes means more genes to perform a variety of functions to support our health.

When there isn’t a wide enough array in a person’s gut, it’s called dysbiosis. You might hear people saying gut dysbiosis is bad and scary, and that you need probiotics to “fix” it. You may also hear that dysbiosis causes leaky gut, also known as intestinal permeability.

(You can read more about leaky gut later in this article, but long story short: There’s no agreed-upon way to diagnose leaky gut, and it’s not something you need to worry about.)

It’s true that dysbiosis can cause problems or signal there’s a problem in your gut, and that probiotics might help. But not always. That’s because…

There’s no single “healthy” gut profile.

A healthy person’s gut profile (or the different types and amounts of microorganisms they have in their gut) could look completely different from another healthy person’s gut.

The same goes for people with various diseases: two people with the same GI disease, for example, may have vastly different gut profiles.

So while probiotics can help in certain situations (see them here), there’s still a lot we don’t know about how our gut works and what probiotics can do. And when it comes to gut health overall, I often say we’re being sold a problem so we can buy a solution.

That’s why it’s important to keep your eyes and ears open for disinformation and sales tactics related to gut health.

In particular, watch out for anyone/anything claiming that:

- gut dysbiosis, gut imbalance, or leaky gut is the cause of any disease

- they can diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent dysbiosis or leaky gut

- you need supplementation, detoxing, or any sort of “gut reset”

- they can design a specific diet for you based on the microbes in your gut

- there’s a specific profile of a “healthy” gut or dysbiosis

- they have the ability to directly modify your gut microbiota in a specific way

- studies from rodent or cell culture are directly representative of the human gut microbiome

The bottom line: There’s still so much we don’t know about the gut microbiome that it’s impossible to define “good” or “bad” gut health.

What’s more…

The benefits of probiotics aren’t a sure thing.

At most, we have moderate evidence that certain probiotic strains might help alleviate certain health issues.

Turns out, it’s very tricky to do research and draw conclusions on the benefits of probiotics. That’s because:

There are hundreds of known strains of gut bacteria.

And potentially hundreds or thousands more that we haven’t been able to identify yet. It’s going to take a while to sift through them all and understand their effects.

Designing high-quality research is tough.

There’s no standardization in:

- Probiotic strains

- Dosage for trials

- Treatment time

So when we look at the outcomes of different studies, they may not be comparable due to how the research was designed. That can make it difficult to draw conclusions.

Much of this research is done on animals.

These studies are useful in telling us how things might work in the gut, but we can’t extrapolate the findings to humans.

There may be some bias in which strains get studied.

Certain strains tend to come up more often in research than others. When scientists see that a certain strain seemed effective in one study, they might (consciously or unconsciously) select it for another study.

Also, some research may be funded by commercial entities (for example, a specific brand of yogurt), which affects which strains are studied.

Ultimately, this all means we have less information about some strains, and more information about others.

Response to probiotics is highly individual.

A supplement might work wonders for one person—but offer no benefit to another—due to differences in gut profiles and other factors.

What’s more, some people appear to be resistant to supplementation.

One study had a group of people take a Lactobacilli supplement.3 Then, researchers sedated each volunteer and then inserted a long, flexible tube into their intestines to see if the probiotic strains had successfully enriched their gut.

(If this sounds hauntingly like your last colonoscopy, you’d be right on.)

Researchers also asked volunteers to hand over their feces for analysis.

The results? The scientists found remnants of the probiotic in everyone’s poop. But during the colonoscopies, they discovered some participants’ guts weren’t enriched with the probiotic strains. For these people, the probiotics essentially passed right through them. So…

Finding #1 was that people responded differently to the probiotic strains.

Finding #2: Fecal counts were not a reliable measure of how well a probiotic “worked” in this study. And most studies use fecal counts as their main measure of how well a probiotic “worked.”

Which leads us to…

Measuring whether probiotics “work” is tricky.

Just because you pooped out microbes doesn’t mean they took up residence and started multiplying in your gut, as evidenced by the study mentioned above. But taking samples from a person’s gut requires, well, getting a tube stuck into your intestines. And it’s not always easy to find enough people who are willing to endure that in the name of science.

The benefits of probiotics: When is a supplement a good idea?

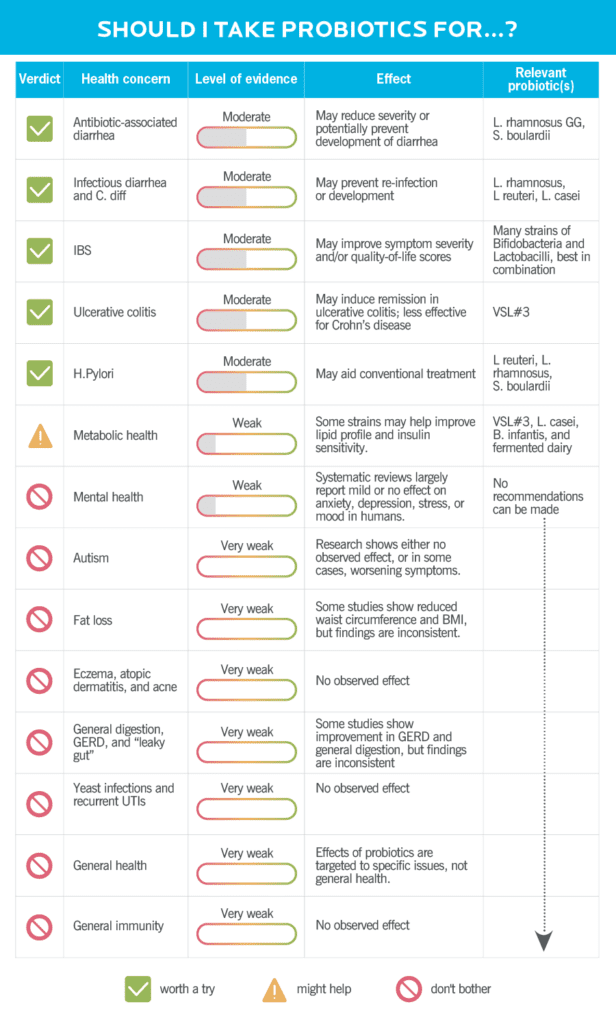

Check out the chart below to see the health concerns probiotics are shown to help with. After that, I’ll delve deeper into each issue individually.

Right now, probiotics are only shown to be beneficial for a handful of specific health concerns.

One thing I need to get out of the way:

There’s no probiotic supplement that works like a multi-cooker—solving five different problems all at once.

Instead, probiotics work more like a bread maker with a persnickety on-off switch. They only do one thing, and they only do that one thing… sometimes.

Probiotic supplements are both strain-specific and population-specific. So there’s no need to pop them the way you would a multivitamin.

You have to be taking the right strain for the right job, and there has to be some evidence that the strain can actually do that job. Even then, there’s no guarantee a probiotic will help solve the problem.

So a crucial first step in deciding which probiotic to take is to ask yourself:

Why do I want to take a probiotic?

Because based on what we currently know, probiotics may help in just a few specific situations.

Taking a probiotic may be helpful if:

You’re taking antibiotics.

Antibiotics kill off some of your gut’s microbes, which can cause a form of dysbiosis. (Remember, dysbiosis is when you don’t have enough diversity in your gut.)

This type of imbalance provides opportunities for pathogenic bacteria (the nasties that make you sick) to multiply and take over. That’s why some people get diarrhea while taking antibiotics.

One example: Clostridium difficile (often called C. Diff) normally hangs out in your gut. But it doesn’t cause problems, because the rest of the microbes in your gut keep it in check. Except, when you take antibiotics, C. Diff might get the opportunity to thrive, which can make you really sick.

So if you have to take antibiotics, taking probiotics alongside them may help reduce the risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea.4 Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii seem to work best.

But you may want to wait and see if you actually get diarrhea before starting a probiotic. Why? Starting a probiotic too soon can backfire when it comes to getting your gut back to normal.

One study dug deeper into this by looking at a healthy group of people who were taking antibiotics.5

Some participants took Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, some took the antibiotics only, and some got a transplant of their own pre-antibiotic poop after finishing their antibiotics (also known as an autologous fecal transplant).

The people who got back to their baseline fastest? The ones who got the fecal transplant, followed by the ones who took the antibiotic alone.

In last place: the group that took a probiotic.

The researchers theorized that the probiotic overpowered the participants’ native microbes, making it take longer to recover.

The takeaway? Since getting an autologous fecal transplant isn’t an option (they’re not FDA-approved for this purpose and, well, they’re a little inconvenient), the next best things are:

- Do nothing, and only use a probiotic if you get antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Take Saccharomyces boulardii along with your antibiotic, which has been shown to help, but doesn’t seem to have the same overpowering effect as Lactobacilli strains.

You have infectious diarrhea.

Got a stomach bug that’s causing diarrhea or traveler’s diarrhea? Taking Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG or Saccharomyces boulardii might help.

There are differences between what works best depending on the cause of diarrhea, as well. For instance, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG seems to work better for diarrhea associated with C. Diff infections than it does for general infectious diarrhea.6 If you’re not sure which to try, consult your doctor or pharmacist for their advice.

You have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus probiotics appear effective for reducing symptom severity in people with IBS.7,8,9

Caveat: Because some of the research uses quality of life scores and most of the strains seem to offer the same effect, there may be a placebo effect at play.

Still, if you have IBS, it may be worth it to give probiotics a try. Some research suggests taking a single strain on a short-term basis (8 weeks) is most helpful.10 Other research notes that a combination of Bifido and Lactobacillus works best, particularly if constipation is a problem.11 (Remember how I mentioned it’s tough to draw conclusions from probiotics research? This is a good example of that.)

So if you’re thinking of taking a probiotic for IBS, consider checking in with your gastroenterologist or a registered dietitian experienced with GI disorders about which strains to try.

You have ulcerative colitis.

Ulcerative colitis, a form of irritable bowel disease, may respond well to certain probiotic strains.

In particular, VSL#3, which is a combination of several different strains, may induce remission and prevent flares. Unfortunately, researchers haven’t seen the same consistency in treating people with Crohn’s disease.

You’re being treated for an H. pylori infection.

Heliobacter pylori is a type of bacteria that can live in your digestive tract and cause ulcers. Certain strains (Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Saccharomyces boulardii) may have a synergistic effect with conventional treatment. And if you’re being treated with antibiotics, it could reduce any associated diarrhea.12

You want to reduce your cholesterol/improve heart health.

File this one under: Probiotics might help, but certainly shouldn’t be the primary thing you do to improve your cardiometabolic health.

Some evidence indicates that certain strains can improve lipid profiles, meaning we see reductions and either total or LDL cholesterol, as well as improved insulin sensitivity.13,14 In the case of cholesterol, the findings were specific to fermented dairy (think: yogurt) rather than a supplement.

Before you read on…

I’m about to tell you about a bunch of situations when taking a probiotic isn’t going to help.

You might respond to some of these by thinking something like:

“But I saw a study/article/documentary saying probiotics help with [fill in the blank]!”

That’s great! This is an exciting and emerging area of research, and we’re learning new things about probiotics every day.

But scientists don’t consider one or even a few studies showing a positive effect to be high-quality evidence. In order to draw a conclusion, a given effect needs to be repeated in several studies, and ideally reviewed and analyzed in a systematic review or meta-analysis.

So, for the health situations below, this may mean that:

- There hasn’t been research on probiotics and this health issue.

- There has been research, but not enough to draw a conclusion.

- There has been research, but the effects observed are inconsistent, negative, or non-existent.

We may eventually discover that probiotics DO help with some of these health concerns. But at the moment, there’s not enough evidence for health professionals to make recommendations they can stand behind.

Phew. [Deep breath.]

Probiotics are unlikely to help if:

You’re dealing with depression, anxiety, or another mental health concern.

Yes, the gut-brain axis is a thing. But we still have a lot to learn about it.

Much of the mainstream discussion around using probiotics for mental health revolves around the idea that if your gut produces more serotonin (sometimes called the “happy hormone”), you’ll have better mental health.

While it’s true that 95 percent of your body’s serotonin is produced outside the brain (including in the gut), this isn’t the exact same serotonin that makes you feel happy.15

Serotonin produced in the gut doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier, meaning it won’t impact your mood.

Why am I pointing this out? The science simply doesn’t support the idea that having more serotonin in your gut means you’ll have better mental health. And overall, the evidence for using probiotics to help treat the following mental health issues is weak:16

- Depression: It looks like probiotics might have an antidepressant effect, but there’s not enough evidence to say that definitively.17

- Anxiety: Preclinical studies in rodents show a benefit, but, so far, these benefits haven’t been observed in humans.

- Mood: In general, it seems probiotics may have an effect on mood. But researchers are careful to note that at the moment, we don’t know enough to make recommendations.18

Importantly…

Probiotics should never be used in place of traditional mental health treatments. (Seriously.)

And even if you’re considering probiotics as something to try alongside therapy or medication, it’s probably not worth it.

Autism and probiotics: Can they help?

People with autism tend to report a range of GI symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation.

This leads some experts to wonder:

Is an imbalance in gut flora to blame?

Unfortunately, we still have more questions than answers. In several studies that included people with autism, GI and behavioral symptoms sometimes worsened while they were taking probiotics.19

There’s also been lots of buzz about the promise of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in people with autism. (You can read more about FMTs below!)

One study did show behavioral symptoms improved over time when people with autism received FMTs, but there was no control group, or a group of people who didn’t receive FMT treatments.20

So while the findings seem promising, it’s impossible to say whether improvement could be attributed to FMTs without a control group.

You want to lose weight.

It’d be so nice if probiotics could help us lose fat. Unfortunately, there’s no compelling evidence that probiotics can help with fat loss. Some studies have shown a reduction in waist circumference or BMI, but the effects are too inconsistent to draw conclusions.21

You have a rash or acne.

As of now, probiotics are not recommended for eczema, atopic dermatitis, acne or any other skin complaint.22,23

You have GERD.

For those experiencing discomfort related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, probiotics may seem like a nice alternative to conventional medications. Unfortunately, while some early study results have seemed promising, they’ve been inconsistent. So there’s not enough evidence to show that probiotics can help in this situation.24

You have occasional gas or other digestive issues.

If you’re wondering if probiotics can help with intermittent gas or stomach upset, the answer is no. Research shows probiotics don’t help with indigestion that has no specific, diagnosable cause.25

You’re concerned you have a leaky gut.

Though intestinal permeability, aka “leaky gut,” has been associated with various diseases and certain medications, it’s not something that can be diagnosed as a health problem (despite what Instagram “experts” may say).

When a person does have intestinal permeability, they won’t have any outward symptoms of that issue specifically—though it’s possible they may have other digestive complaints.

And regardless of whether you believe leaky gut is a “thing,” there’s no evidence probiotic supplements help repair the gut lining in people with intestinal permeability.

You have a yeast infection or recurring UTIs.

People often look for natural alternatives to treating these issues, but probiotics are unfortunately not proven to help with yeast infections or prevent recurring urinary tract infections.26,27

You want to be the healthiest person on your block.

You’re better off making lifestyle changes to support your overall health than taking a probiotic.

You want to “boost” your immune system.

We know that probiotics can play a role in enhancing immunity in certain specific situations.

For example, when you take a probiotic to help with infectious diarrhea, that’s a function of immunity. And one study showed probiotics might reduce the severity of upper respiratory tract infections in athletes.28

That said, for overall immune health—something a lot of people are interested in now given the pandemic—there are quite a few other changes you can make that will have a greater impact. (To learn what they are, check out this infographic on how to optimize your immunity.)

Fecal transplants: Are they evidence that probiotics work?

Sometimes, people cite the success of fecal transplants as evidence that probiotics work.

But what is a fecal transplant, exactly? The technical term is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). Basically, a healthy person’s stool is mixed with saline and then inserted into the patient’s colon.

So yes, we’re talking about poop transplants here.

We don’t know exactly how or why FMTs work, but they’ve been shown to be 80-90 percent effective in helping people with C. Diff infections that don’t respond to other methods of treatment.29

It’s thought that FMTs might help these patients by repopulating their gut with microbes that edge out C. Diff.

These results made scientists wonder about their other potential applications: In people with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, autism, obesity, and more.

Despite great hopes for FMTs, results have been mixed in trials using them in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.30 And in trials with people with obesity, no effects were observed on body weight or composition.31,32

At the moment, fecal transplants are only approved by the FDA for treating C. Diff after other treatments haven’t worked.

And does the success of FMTs underscore the effectiveness of probiotics? Not really.

Probiotics contain a much smaller number of strains and a much lower total microbial content than FMT preparations.

So essentially, just because FMTs seem to work in people with C. diff does not necessarily mean everyone should be taking probiotics.

Taking a probiotic 101: The most common questions, answered

Question #1: How do I choose a probiotic?

You’ll need to consider several factors.

Factor #1: Species, strain, or multi-strain probiotic

The species or strain(s) that will make the most sense for you depends on the reason you’re taking a probiotic. Refer to the chart above to see which specific probiotics are relevant for you.

Factor #2: Price

In most cases, taking a probiotic is a short-term thing, so price may not be a huge factor. But if it’s something you’d need or want to take long term, consider: Is the financial commitment reasonable for you?

And could you get the same benefit from lower cost (and potentially free) interventions, such as eating more whole foods and fewer highly-processed ones? (Learn more: The 5 principles of good nutrition.)

Factor #3: Dosage

We know that the effective dose for all probiotics is somewhere between 106 to 109 colony-forming units (CFUs). (FYI, those little numbers mean ‘10 to the sixth power’ and ‘10 to the ninth power. Or simply: 1 million to 1 billion CFUs).

Look for probiotics that deliver this dose in one or two administrations per day.

Also: Be sure to take probiotics before their expiration date. If you take them afterwards, you may not get the number of CFUs on the label.

And… that’s it. Don’t worry about whether your product is refrigerated. (Turns out, that doesn’t matter.)

When it comes to third-party quality certifications, these aren’t as important as they might be for protein powders and other supplements. But if you’re an athlete and want to be extra safe, it’s not a bad idea to look for a probiotic certified by NSF or USP.

The most important thing is matching up the right strains with the right health problem.

Question #2: When should I take my probiotic?

It’s best practice to take probiotics right before a meal, which seems to increase the odds of the little bugs doing their job in your digestive tract.33

If you’re on antibiotics, it’s natural to wonder if the antibiotic will wipe out the probiotic. After all, antibiotics kill bacteria, right?

The short answer: You don’t really need to worry about this; your probiotic will be fine. (And if you’re concerned, you could ask your doctor or pharmacist about antibiotic and probiotic timing.)

The long answer: Antibiotics do kill bacteria. But they work in different ways.

Some antibiotics disrupt the cell wall or membrane of the bacteria they target, others prevent protein synthesis so the bacteria die off, and others damage the bacteria’s genetic material.

Because of this, antibiotics don’t kill all the bacteria they come into contact with, so they may or may not affect the probiotics you take. And they may or may not affect your native microbiome.

Also, some probiotics are yeasts, like Saccharomyces boulardii, so they’re not affected by antibiotics.

(And to be honest, as an expert in this field, I’m less concerned about antibiotics throwing our native microbiomes off-kilter than I am about bacteria in our guts developing antibiotic-resistant genes. This is caused by antibiotic abuse or misuse, and can cause antibiotics to stop working when we really need them. But that’s another topic entirely…)

There’s also this: No matter when you take your probiotic and antibiotic, they’re both going to be hanging around in your GI tract for about a day.

That means to some degree, everything is going to get mixed together anyway, which is why this really isn’t something to be concerned about.

Quick question: Can probiotics survive stomach acid?

Yes, they can.

Most probiotic capsules are coated in a way that prevents stomach acid from getting to them. Once they reach the small intestine, the coating is dissolved.

There are even some types of Lactobacilli that live in the stomach. So the idea that stomach acid kills all probiotic strains isn’t quite right.

Question #3: How long will it take a probiotic to work?

There’s no standardization in how long you should take probiotics.

If you’re taking probiotics for antibiotic-associated diarrhea, you’ll want to take them until you’re feeling better. This could be anywhere from one to eight weeks, for instance. But if you don’t notice any improvement in your symptoms after a month, it may not be worth continuing.

If you’re taking probiotics for IBS, some research suggests people do better when they take them for shorter periods of time, as in less than eight weeks.

As a general rule of thumb, I’d recommend taking a probiotic for a month. Then, use the steps directly below to determine whether it’s working for you.

This works out conveniently, since most probiotics are packaged in a one-month supply. That way, you can make a decision about whether to continue before you buy more.

Question #4: What are the signs your probiotic is working?

To answer this question, you want to be really clear on what you hope to achieve by taking a probiotic.

Let’s say you’re hoping for improvement in your IBS symptoms.

You’ll want to set up a little self-experiment to evaluate whether probiotics are helping or not.

So start by asking: What would “improvement” look like?

Maybe it’s that you’re able to get through an entire day at work without digestive discomfort.

Or a week without having to miss out on something you wanted to do because of your IBS.

Or it could be more specific: less diarrhea, constipation, or stomach cramps.

Whatever parameters you decide on, the next step is to get in touch with your inner scientist. (We’ve all got one lurking in there!)

Collect your data. Grab a journal or keep notes in your phone, and track any changes you notice.

You might keep track of data points like your daily symptoms (or lack of symptoms) and/or your bowel movements and their qualities (using the examples in this handy visual guide to poop health).

Every two weeks, reevaluate. How are things measuring up against the metrics you decided on?

Over time, you’ll see a trend. Either the probiotics are helping, or they’re not. And from there, you can decide on your next move.

Question #5: Are there any side effects?

Probiotics can sometimes worsen GI symptoms. It’s pretty uncommon, but they can occasionally cause bloating or diarrhea.

It’s also important to be aware of potential drug interactions. For instance, people on oral chemotherapy drugs should check with their doctor before taking probiotics.

(And really, if you’re on any prescription medication, it’s a good idea to check with your doctor before starting a new supplement.)

Lastly, in people who are extremely immunocompromised, there’s the potential for bacterial or fungal translocation.

That basically means if you have a big ulcer, it may be big enough for bacteria or yeast from probiotics to pass through and get into the bloodstream. And that would cause a total body infection, which is really dangerous.

Of course, this is a rare complication but worth noting for people with a compromised immune system.

How to support a healthy gut without supplements

If you came to this article wanting to ensure you’re looking after your gut health, this section is for you.

When people ask me if they should take a probiotic or if there’s anything in particular they can do for better gut health, there are two big questions I want to answer:

- Are they getting enough fiber from a variety of sources?

- Are they getting enough physical activity on a regular basis?

I ask these questions because these are the two biggest factors that seem to determine microbial diversity.

So if you’re interested in taking probiotics for general health or for one of the issues listed in the “probiotics are not likely to help” category, you’ll want to be sure you’re implementing these two lifestyle changes first.

Not only are they often less expensive than probiotics, but they’re more likely to improve your health overall. Also, if you’re taking probiotics for purpose there’s good evidence for, these practices will be supportive.

Lifestyle change #1: Eat a nutrient-dense diet with enough fiber from a variety of sources.

If you want to support a diverse microbiome, this is probably the most important thing you can do.

Eating a wide variety of fiber-rich foods like fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds is your best bet. Add in some lean proteins and healthy fats and you’ve ticked the nutrient-dense box, too.

This whole fiber thing is really important.

One probiotic study done on healthy bodybuilders looked at the group’s gut profiles.34

Though it wasn’t the main aim of the study, the researchers noticed that bodybuilders who didn’t get enough fiber had microbiomes similar to people who were sedentary.

In other words, they weren’t getting the microbiome benefits of exercise (more on that in a sec), possibly because they weren’t eating enough fiber.

Interesting, right?

What are prebiotics?

You may have heard that you should be eating prebiotics, a form of fiber that “feeds” the microbes in your gut. If you regularly eat fiber-rich foods like the ones mentioned above, you’re getting enough prebiotics in your diet. We don’t know which microbes prefer which types of fiber yet, so eating a wide array of different fiber sources is the best approach.

What about probiotic foods?

Probiotic foods may also be worth including in your diet. They’re associated with a host of beneficial health outcomes, such as a lowered risk of cardiovascular disease.13

And just a reminder: The only food that’s classified as probiotic right now is fermented dairy. This includes fermented yogurts and kefir.

What happens if a fiber-rich diet causes GI issues?

Sometimes, people eating a whole-food, fiber-rich diet experience bloating, diarrhea, and other digestive symptoms. This can be confusing, especially if you’re putting a lot of effort into eating well for health reasons.

In this situation, people often wonder if there’s something wrong with their gut health or if they need to take a probiotic.

The answer: probably not.

The bacteria in your gut ferment some of the fiber you consume. As they do so, they produce gas. That’s not a sign of poor gut health. It’s just a natural response to eating more fiber.

But if eating more fiber-rich foods causes noticeable and sustained GI symptoms, it’s a good idea to check in with your doctor.

If you get a clean bill of health or if your doctor has ruled out everything except IBS, the next step would be to start a personalized FODMAP elimination and reintroduction diet with the help of a specially-trained nutritionist or dietitian.

(To learn more about FODMAPs, and for everything you’d ever want to know about doing an elimination diet check out Precision Nutrition’s FREE downloadable e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Elimination Diets.)

Lifestyle change #2: Incorporate movement on a regular basis.

In general, exercise is a good thing for your microbiome. Active people tend to have more microbial diversity, research shows.35 So commiting to a regular movement routine is a great next step for gut health.

But there is a sort of ‘Goldilocks effect’ with exercise.

For instance, endurance exercise is associated with something called exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome, and people with IBS may notice discomfort with intense exercise.

So like anything else, you need to find the right balance that works for you.

Focus on physical activity that:

- you actually enjoy

- you can do regularly (i.e. several days a week)

- makes you feel good and energized, not drained or sick.

Extra credit: Focus on deep health.

If you’ve already got your fiber and exercise habits down, that’s great news. Wondering what else you can do?

There’s a lot of talk about the impact of sleep, stress, and other factors on gut health, but we don’t have much in the way of human data on how they impact microbial diversity.

How does alcohol impact gut health?

We know too much alcohol can be detrimental to gut health.

But interestingly, moderate red wine consumption seems to be associated with greater microbial diversity, possibly due to the polyphenols in wine.36

And actually, these effects are more realistic than the resveratrol buzz we always hear about red wine, because all polyphenols seem to interact with our microbiota.

So I’d recommend drinking rarely, or in moderation of red wine specifically.

(Wondering if you’d be healthier if you quit drinking? Find out in this article on the real tradeoffs of alcohol consumption.)

So as a next step for people who have the two main lifestyle changes down, I recommend focusing on practices that support your deep health, or your overall health.

These can also help you make intentional decisions about what you eat and how you move, bringing it all full circle.

What do those practices look like? Some places to start include:

- Managing stress

- Getting enough sleep

- Taking care of your emotional and mental health

- Seeking connection through meaningful relationships

- Shaping your environment to support your health and wellbeing

This might seem a little anticlimactic if you’re really charged up about getting better gut health.

I get it. The microbiome is a fascinating area of research. But in the scheme of things, we have very little in the way of practically-applicable data.

While we wait for more evidence, we do know this: The behaviors that are associated with many other positive health outcomes may also be beneficial to our microbes.

That’s actually good news, because it means in most cases, we don’t need fancy, expensive supplements for a better microbiome.

So the stuff that’s good for your overall health? It’s probably also good for your gut.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, preferences, and circumstances—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

[ad_2]

Source link