[ad_1]

AsianScientist (Feb. 11, 2021) – Last year, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier—pioneers of the gene-editing technology CRISPR—made headlines worldwide for being the first two women to share the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. As historic as their win may be, their very achievement highlights how rarely such prestige is afforded to women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

At present, less than 30 percent of all researchers worldwide are women. Singapore matches the global average, with women making up 30 percent of the country’s 35,000 plus-strong researchers and engineers in 2018. To encourage full access to and participation of girls and women in STEM, the United Nations General Assembly declared February 11 as the International Day of Women and Girls in Science in 2015.

With Singapore’s Ministry of Social and Family Development designating 2021 as the Year Of Celebrating SG Women, it seems timely to revisit—and rethink—local perceptions regarding girls and women in STEM fields. To this end, Asian Scientist Magazine in collaboration with international market research firm YouGov, surveyed 1,064 Singapore-based respondents. The resulting figures have been weighted to be representative of all adults aged 18 and over in the Republic.

Mind the gap

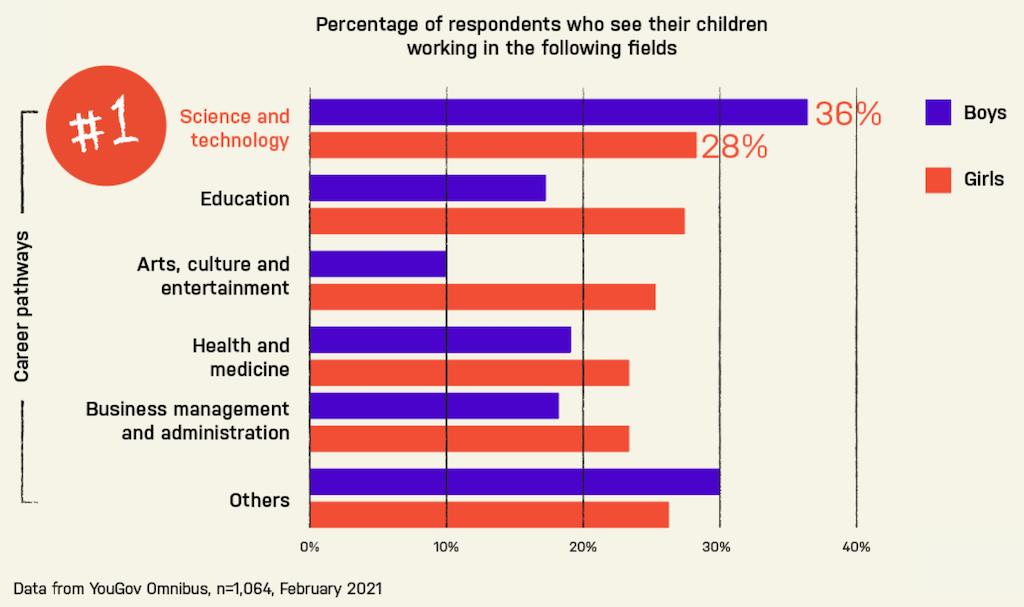

For local parents with children under the age of 18, science and technology is the most popular career choice for their offspring—with 36 percent and 28 percent respectively envisioning their male and female children taking up STEM careers. Inside the classroom, most of parents believe that boys and girls are equally suited to various science and technology subjects such as physics (71 percent), chemistry (81 percent) and biology (83 percent).

While these findings certainly paint a rosy picture, a closer look at these fields of study revealed several gender-based differences. For instance, parents perceived ‘hard’ science subjects like advanced mathematics (21 percent) and design and technology (30 percent) to be more suitable for boys compared to girls. Meanwhile, humanities subjects like literature (27 percent) and art (21 percent), as well as accounting (19 percent), were likewise perceived to be more suitable for girls compared to boys.

Interestingly, a 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America proposed that girls favor humanities subjects due to their comparative advantage in reading compared to boys, rather than any deficiencies in mathematics skills. Therefore, the tendency of girls and women to play to their academic strengths could be driving the STEM gender gap, suggested the authors.

The work continues

To encourage more women and girls to pursue STEM careers, respondents were in support of having dedicated initiatives like increased media visibility (64 percent) and career talks (55 percent) in place. Other measures include bursaries and scholarship schemes from key players in the STEM ecosystem ranging from the government, universities as well as technology and scientific companies.

For all the efforts to increase the representation of women in STEM, it should be noted that gender-based assumptions become even more prominent once students leave school and enter the workforce. In the survey, nearly four in five (79 percent) respondents agreed that gender biases exist in the working world.

True enough, while females make up 60 percent of the student cohort in science courses at Singapore’s universities, women make up only 30 percent of the country’s scientists. The high attrition rate of women in STEM—also known as the ‘leaky pipeline’—has been attributed to various reasons through the years, including family commitments, marginalization and funding gaps at work.

Evidently, there is much work that needs to be done before gender parity is achieved in Singapore’s STEM ecosystem. But through global initiatives like the International Day of Women and Girls in Science and our regular features here at Asian Scientist Magazine, we hope to continue elevating excellent women scientists to the forefront—where they have always belonged.

—–

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine; Photo illustration: Shelly Liew/Asian Scientist Magazine.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.

[ad_2]

Source link