[ad_1]

Names in this story have been changed to protect people in this article from retribution.

At a popular Uyghur restaurant in Istanbul’s bustling Zeytinburnu district, Kerim, a young man from Urumqi, serves customers generous plates of shish kebabs, laghman noodles, and pilaf rice. He points to a sign in the window of the traditional noodle house which says in Chinese, English, and Turkish: “Chinese do not enter.” The shopkeepers put up the sign after numerous unknown people repeatedly came in to watch them, take photos of them, and intimidate them.

“People keep disappearing here, so we can’t relax,” he says.

Now thousands of miles away from stifling surveillance and hundreds of brutal internment camps in western China, the largest Uyghur diaspora community in the world tries to reimagine a small slice of home in Istanbul. Beijing’s relentless “Sinicization” push in Xinjiang province pushed many to seek refuge here after fleeing the region, but most still have family members and friends incarcerated back home. Kerim fled Xinjiang without his family four years ago via Egypt and has been unable to contact his relatives since, leaving him constantly worried about what has happened to them.

At a popular Uyghur restaurant in Zeytinburnu, a sign posted outside says: “Chinese do not enter.” Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Today, three Istanbul neighborhoods host much of Turkey’s sizable Uyghur population. Here, blue East Turkestan flags (a symbol of independence banned in China) are openly displayed in shop windows. One can also find authentic pulled noodles and fresh naan flatbread, shop for traditional attire, and read Uyghur literature in bookstores.

At the end of every week, in this diverse community with a large amount of Central Asian emigres, elderly Uyghur men with long beards and traditional doppas (skullcaps) can be often seen making their way to the Ulu Mosque for Friday prayers, sliding prayer beads through their fingers. Those fortunate enough to make it to Turkey desperately try to hang onto the old traditions that were lost back in Xinjiang, where these cultural practices and symbols have been banned.

The Ulu Mosque in the Zeytinburnu district of Istanbul. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Increasingly since 2017, Chinese authorities have taken brazen actions against the Uyghurs. Beyond the banning of their culture, their religious activities have been deemed “illegal” under the guise of combatting terrorism, and scores of Uyghurs have been sent to prison camps after sham trials for activities the government loosely deems “extremist.”

In new accounts from a BBC investigation in early February, Uyghur detainees shared stories of surveillance, internment, indoctrination, dehumanization, sterilization, torture, and rape. Many activists, media, and Uyghur experts have labeled China’s actions in Xinjiang crimes against humanity and a “cultural genocide.” The U.S. State Department said it was “deeply disturbed” by the BBC reports.

Uyghur women shopping on one of the main streets of Zeytinburnu. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

From Kashgar to Istanbul

Along one of the main streets in Zeytinburnu, I meet Fatima, a student from Kashgar. She has good English and is open to speaking as I enter her family’s store. She and her mother fled Kashgar in 2014. They initially went to Cairo to seek asylum, but after nearly two years they were denied the right to stay.

As many have done for decades, her family then fled to Turkey, which has been an attractive option as a long-time haven for Uyghur exiles. Fatima now studies English at a local university and her parents run a shop in the heart of the district where they sell traditional Uyghur clothes and other merchandise to their fellow Uyghurs.

“At home, it is impossible to find these items now, and it is dangerous to even own them in Kashgar. We run this store to keep our heritage alive, and it is a space for others in our community to come and feel safe, have a sense of home,” she says. As much as she misses Kashgar, the “cradle of culture” for the Uyghurs, she knows that she will likely never return.

A shop owner selling traditional Uyghur dress. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Much of Kashgar’s old city has been razed in what the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) called China’s “campaign to stamp out tangible aspects of Uyghur culture.” UHRP describes the city as on the “front lines of the most aggressive, high-tech surveillance campaign of the 21st century” and “the target of a vast and totalizing anti-historical ‘modernizing’ reconstruction project” that the group says seeks to eradicate Kashgar’s “immense cultural and historical significance.”

Fatima agrees with those characterizations of her homeland, but is nervous about what she sees happening in Istanbul, too. Many in the Uyghur community feel a growing sense that they are under threat, bordering on a state of paranoia, because of news of deportations happening around them.

“The level of distrust in the community is growing as people we know keep getting detained,” she says.

Despite the situation, Fatima is confident that she will soon obtain Turkish citizenship, giving her a sense of safety and freedom to speak out.

“What happens here has consequences for those back home too,” she says.

This may be a false sense of security though, as Uyghurs even with Turkish passports have been extradited and ended up in camps.

Fatima feels lucky she was able to leave the country when she did with her mother, but her father is still there. The rare optimism she exudes in an often tense atmosphere is because she hopes she and her family will not have to flee “home” again, but be allowed to remain in Turkey. According to reporting by the Financial Times, Chinese officials have pressured scores of Uyghurs abroad to immediately return by detaining their parents.

A few weeks ago, someone Fatima knows who works at a local shop disappeared.

“This is happening every day, every week here in Zeytinburnu, Fatih, and Sefakoy. Someone’s parent is gone now,” she says.

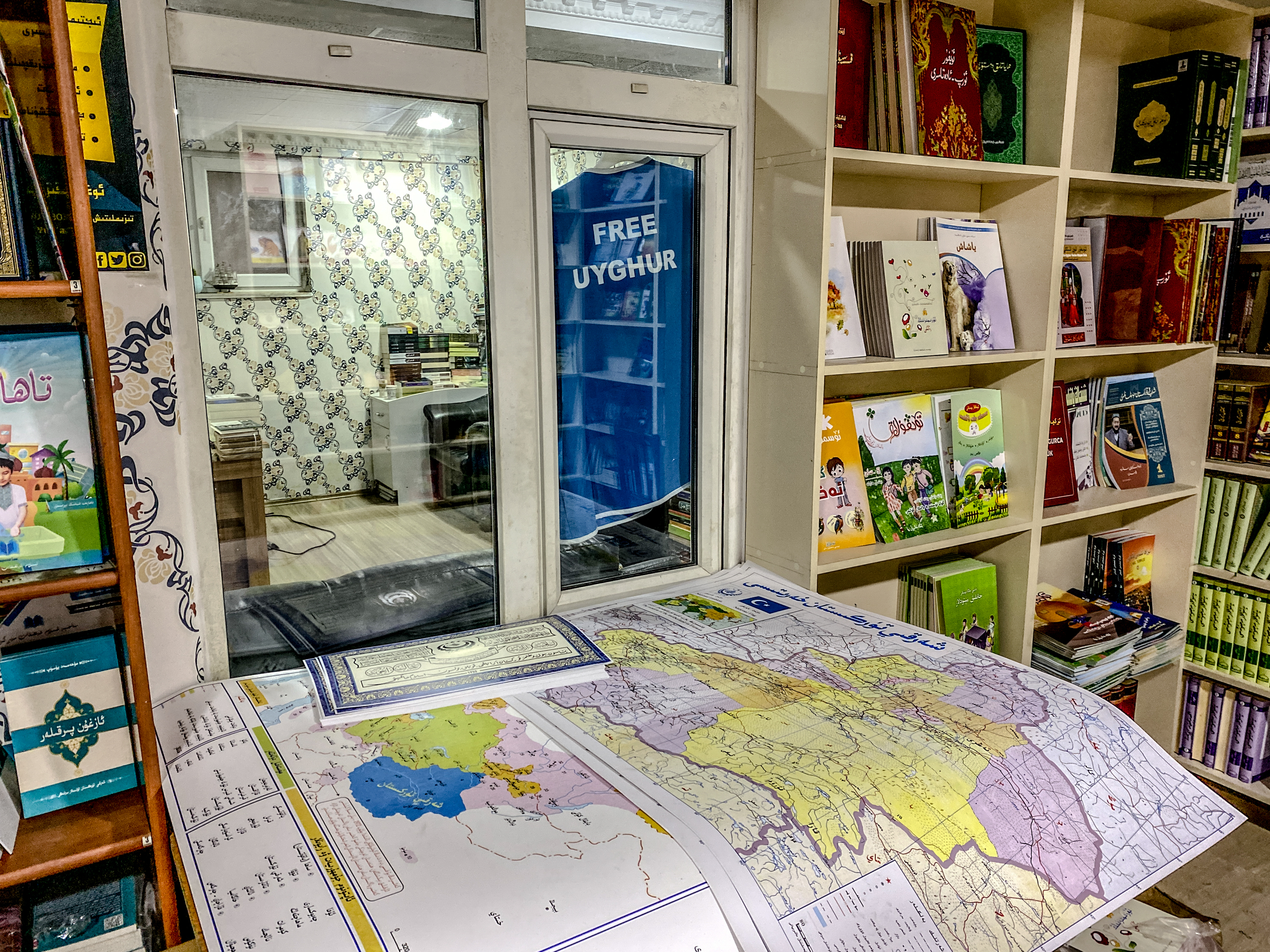

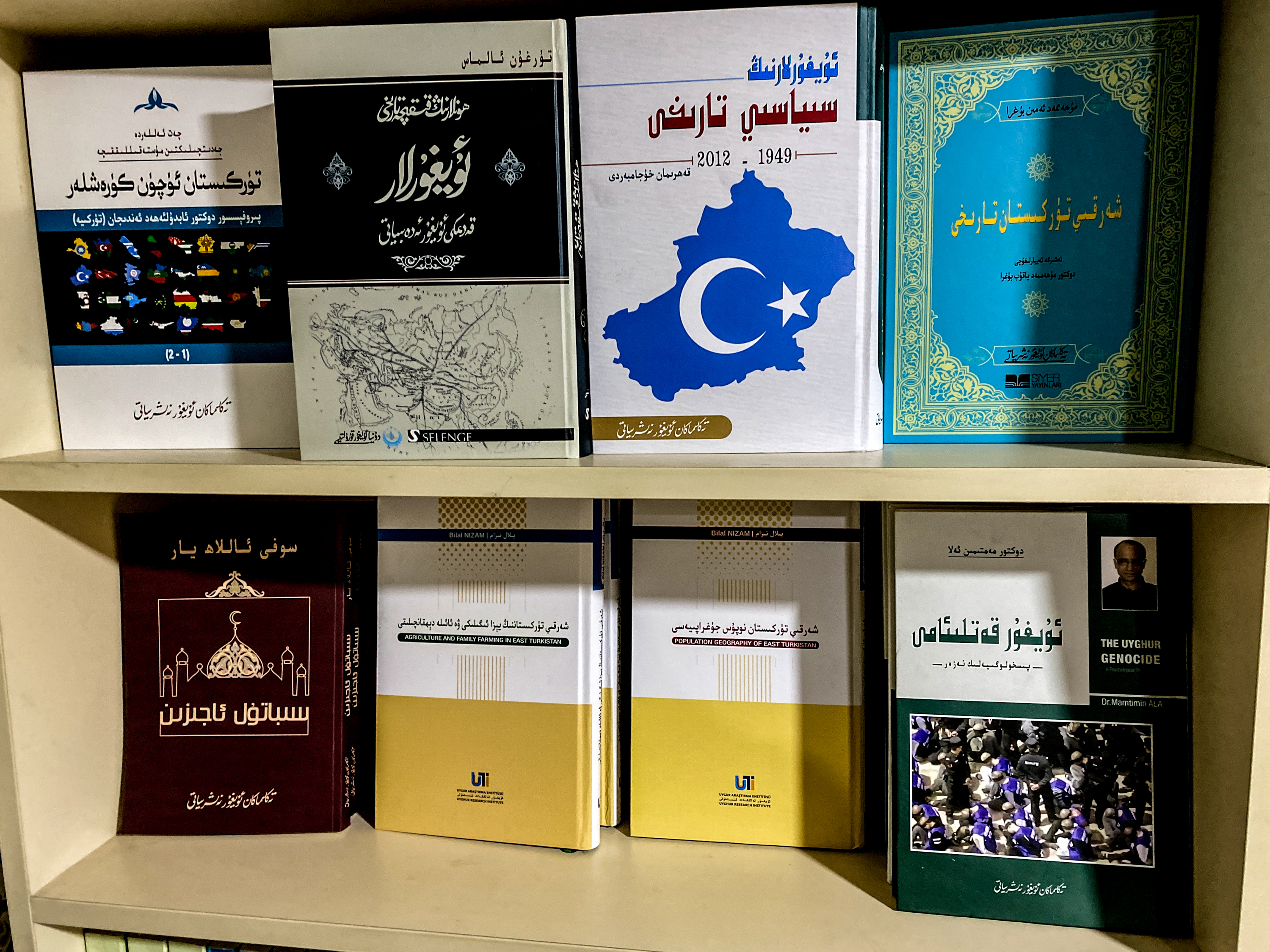

Bookstores: Safeguarding Uyghur Language

In addition to enduring imprisonment and torture, authorities in Xinjiang have taken swift measures to decimate Uyghur culture and identity: destroying religious sites, eliminating Uyghur-language education in schools, and banning Uyghur literature. Mass detentions have targeted intellectuals of all stripes: academics, writers, musicians, and poets.

At the Taklimakan Uyghur Nesriyat bookstore, Ershat Bahtiyar, from a small town near the Kazakh border, spends his days digitizing older volumes of books written by famous intellectuals. He left his town in 2017 to study at Al-Azhar University in Egypt, where many Uyghurs have studied abroad, and then moved to Turkey. Bahtiyar tells me that he hasn’t had any contact with his family for two years.

Through books, he feels a sense of connection and sanctuary. As one of three Uyghur bookstores in the city, it is Turkey’s oldest Uyghur publishing house, holding over 3,000 titles. Possession of books sold here would be punishable by years in prison under a charge of “subversion of state power” in China.

The Taklimakan Uyghur Nesriyat bookstore in Zeytinburnu. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Back in Xinjiang, in state-run bookstores, the ban on the Uyghur language started three years ago. This meant literature, religious books, and historical texts were removed from the shelves. Today, across the province, bookstores reportedly sit empty and private bookshops have been closed, likely meaning that their owners were taken into custody.

A campaign to get Xinjiang residents to exclusively use the “national language,” Mandarin, has seen the Uyghur language forced out of schools, while the Uyghur script has been removed from many signs. Minorities across China have voiced concerns that their next generations will not be able to read or write in their native languages as minority languages are being purged. Uyghur booksellers in Istanbul agree.

Rolled out a decade ago, China’s larger Mandarin promotion policy has been aimed at “assimilating” China’s 55 minority groups. Along with Xinjiang, where students were formerly taught in Uyghur and Kazakh, the policy has also been especially tough in Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and most recently, in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture.

Close to 12,000 Chinese citizens have been charged and jailed for “inciting separatism.” It’s a common tactic used against members of ethnic minorities who irk the government, particularly in Xinjiang and Tibet, but also following protests in Inner Mongolia last August. This targeting isn’t new: authorities targeted Uyghur intellectuals after the People’s Liberation Army occupied Xinjiang in 1949, and even earlier, in the late 1930s, when Xinjiang was governed by a Soviet-backed leader.

Many Uyghur books sold in bookstores in Istanbul are written by now jailed authors. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Brutality Back Home

According to The Economist, the latest figures estimate that at least one in 10 Uyghurs have been sent to the camps. After international scrutiny in December 2019, the governor of Xinjiang announced everyone had “graduated,” but subsequent reporting has disputed his claim. From survivor statements to the Associated Press, the “graduation” has actually meant people are being forcefully shifted from “re-education centers” to jails, or to work in factories for low wages, often for international brands.

Numerous investigative reports like the “China Cables” have detailed and confirmed many of these accounts. Uyghurs have recounted numerous forms of torture: the cutting of women’s hair for hair transplants sold abroad, organ harvesting, forced factory labor and marriage, mass rape, surveillance, birth control, forced abortion, and sterilization, child abduction, and being made to eat pork.

Xinjiang expert Adrian Zenz found that the authorities planned in 2019 to force at least 80 percent of women to undergo surgeries, implant intrauterine devices, or be sterilized in four rural regions in southern Xinjiang. Birth rates have subsequently plunged by 60 percent in three years, according to the Economist, citing official data in Kashgar and Hotan.

In an early 2021 tweet, the Chinese embassy in the United States openly praised the treatment of its Uyghur minority, stating China was in the process of “eradicating extremism” and had “emancipated” Uyghur women, “making them no longer baby-making machines.” Despite China’s ban of Twitter at home, officials regularly use it abroad to disseminate propaganda. In late January, the Chinese consulate in Istanbul refuted a New York Times story, and offered its version of the situation.

A man shops for produce at a Uyghur-run supermarket in Istanbul. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

A Looming Decision, a Changing Relationship

In Turkey, according to lawyers representing Uyghurs, hundreds have been charged with “activities against China” and taken to deportation centers across the country on terrorism charges. The latest reported cases include three people detained on January 18. NPR reported last year that hundreds had been sent to deportation centers for months on end without clarity as to why. Observers suspect that it is due to increased Chinese pressure on the Turkish government.

Many in Istanbul are torn between being deeply homesick and also constantly paranoid about deportation, knowing they would likely be imprisoned in China for simply being abroad. In Turkey, increasingly difficult residence permits take months to obtain, leaving many without legal status in the country, no work permission, and few means to sustain themselves.

Turkey was considered a champion of Uyghur rights for seven decades, but many in the community are starting to feel their days here may be numbered. Previously, the “Uyghur issue” was a point of contention in Turkish-Chinese relations, but that is now changing. In light of the repatriation agreement between Turkey and China, Istanbul’s Uyghurs are increasingly distressed about their future status in the country, pending ratification of the extradition treaty.

The Turkish parliament reconvened on January 26, but it is still unclear when a debate on the treaty’s approval will be taken up. It could be as early as this month. Even if it is approved, Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said it does not mean “Turkey will release Uyghurs to China. We do not use the Uyghur Turks politically. We defend their human rights.”

The Zeytinburnu district of Istanbul is home to a substantial amount of Uyghurs who resettled in Turkey. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

The Turkish government continues to deny that China is exerting pressure to return Uyghurs to China.

In December of last year, a few days before the first supply of COVID-19 vaccines were to be shipped to Turkey, Beijing announced it had ratified the extradition treaty. Reports then surfaced that the agreed-upon COVID-19 vaccine shipments to Turkey were delayed expressly to exert pressure on the Turkish government to ratify the extradition treaty. Turkey is betting heavily on the 50 million doses of the Sinovac vaccine it ordered from China to stabilize the health situation in the country. Cavasoglu refuted any connection: “Vaccines and East Turkestan or Uyghur Turks have no relation at all.”

Opposition legislators claim that the Turkish government is caving to China. The AP reported on February 5 that tens of millions of doses have still not been delivered. Meanwhile, lawyers told the AP that more than 50 Uyghurs were recently sent to deportation centers. Lawyers and human rights defenders fear the treaty will be broadly used to extradite Uyghurs.

Fresh baked naan flatbread sits in the window of a Uyghur bakery. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Mixed Messages, Shifting Tides

After the People’s Republic of China was established, Turkey quickly became the de facto headquarters-in-exile for Uyghur emigres. The working-class districts of Zeytinburnu and Sefakoy have been traditional safe havens for Uyghur exiles for decades, dating back to the 1950s. In 1952, Turkey offered asylum to Uyghurs fleeing Chinese communists; in 1955, Beijing declared Xinjiang an “autonomous region” of the PRC.

In the early 1980s, a second wave of Uyghurs moved to Turkey following China’s government reform and open-door policy, which allowed them to express their grievances to an international audience. China always considered the Uyghur issue an internal affair, and Uyghurs speaking up abroad brought unwanted attention. In the 1990s Beijing began applying more pressure on Ankara.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was previously deemed a staunch advocate of Uyghurs as mayor of Istanbul in the 1990s and with his comments as prime minister in 2009 calling China’s actions “genocide.” In 2015, he said he would always keep Turkey’s doors open for Uyghur refugees, but on a visit to China in 2019, Erdogan said he had discussed the “Uyghur issue” with Xi, taking a unclear tone. He has not made statements about the extradition treaty’s implications.

Turkey’s diplomatic and economic ties have considerably deepened with China since it loaned the country billions of dollars, and even more funds have been promised to bolster infrastructure mega-projects and buttress the country’s depleted financial reserves amid an ever-deepening economic crisis exacerbated by COVID-19. This is a major shift from just two years ago when the Turkish Foreign Ministry called China’s Xinjiang camps “a great embarrassment for humanity” and called on China to close all of the camps.

Traditional Uyghur doppas (skullcaps) for sale in the Fatih district of Istanbul. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Omer Celik, spokesman of the ruling AKP party said last September, “We support China’s right to fight terrorism. The practices Uyghur Turks face cannot be evaluated in this context. A serious distinction needs to be made between terrorists and innocents.”

Erkin Emet, an associate professor of language at Ankara University, told Buzzfeed, “From China’s perspective, Turkey is the most dangerous place for Uyghurs…because of the common culture and history we share with Turks.”

East Turkestan flags and other symbols important to Uyghurs hang in a shop selling traditional attire. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Like Sitting Ducks

One of China’s chief justifications for pressure on Turkey and other Muslim countries (such as Egypt) for the repatriation of Uyghurs is the claim that Uyghur students are being radicalized abroad. While reports of Uyghurs fighting for jihadist groups in Syria didn’t help, the story goes even further back to the early days of the global “war on terror.” After 9/11 China put forward Xinjiang as a target in the global fight against terrorism and the United States even held Uyghurs in Guantanamo.

Egyptian authorities have stepped up cooperation in the past three years after signing a security agreement with China, deporting and imprisoning about 150 students from Al-Azhar University in Cairo. Some fled in time to make it to Turkey.

In Istanbul, Abdullah Hakim Aziz sells nuts and other produce from his homeland in a modest shop. He fled to Turkey in 2013 through Egypt, where he attended Al-Azhar University. “It’s been five years of no contact with anyone there [in Xinjiang]. I have Turkish citizenship now so I am safe here. In Egypt, I wasn’t,” Aziz says. These days, it is virtually impossible for Uyghurs to legally study or live abroad, and most are denied access to a passport by the Chinese government.

In the Fatih district, a shop sells Uyghur carpets, traditional instruments and dress from Xinjiang. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Uyghurs in Turkey are increasingly worried that what happened in Egypt will soon play out here. Many Uyghurs in the city say they have been harassed by the Chinese government and consulate, warning them not to speak out. Some Uyghurs have had their passports invalidated by the Chinese government, a strategy being employed to make them even more vulnerable to extradition.

In the last three years, Turkey has reportedly deported Uyghurs back to China via third countries, such as Tajikistan. Turkey’s general stance has been to respect extradition agreements made with various countries, deporting exiles back home despite warnings they would likely face severe persecution. In the last decade, Istanbul has quickly become a sanctuary for hundreds of opposition figures and dissidents fleeing conflicts from across the region. Governments have continually attempted and in some instances have successfully targeted exiles and dissidents in Turkey.

What Comes Next?

On January 20, the day of new U.S. President Joe Biden’s inauguration, I met Ramazan from Korla in his shop in the Fatih district of Istanbul.

“Is Biden a friend of China?” he asked me apprehensively.

Ramazan has been in Turkey for eight years. His father and mother are still in Urumqi and he hasn’t spoken to them in the last four years.

“I have no idea what has happened to them,” Ramazan said of his parents.

The emotional and psychological toll is profound. Ramazan retains a huge sense of guilt having left his family members behind and worries about what’s happening in Turkey. “They took 15 people last night in Sefakoy. They are doing it little by little,” he says.

Ramazan has a Turkish passport but is unsure what will happen next. “The area is dangerous. There are always strange men in the neighborhood. Sometimes there are police or others we don’t know,” he says.

Some restaurants have taken down their signs or closed and relocated elsewhere, unmarked, in fear of the authorities finding them.

“Many don’t even have a temporary residence permit here and are scared,” Ramazan says.

On February 11, Biden pressed Xi on Xinjiang in their first call.

Blue independence flags are openly displayed in Uyghur shops around the city, something forbidden back home. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Demanding Answers, Voicing Support

Over the last two months outside the Chinese consulate in Istanbul, dozens of Uyghurs desperate for answers have stood holding pictures of their loved ones still missing back home. After weeks of protests, the Chinese consulate said they would consider the protesters’ petitions, which briefly paused the demonstrations. But on January 27 the Chinese consulate again refused to officially accept petitions filed by the families of the camp victims. A day earlier, on January 26, Mayor of Istanbul Ekrem Imamoglu offered support as an intermediary, but holds little influence over the situation.

Standing outside the Chinese consulate, a mother holds photos of her missing family members. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Turkish civil society has long backed the Uyghurs in Turkey, referring to them as their “brothers.” In December 2019, thousands marched in Istanbul in support of the Uyghurs, while expressing solidarity with popular German-Turkish Arsenal soccer star Mesut Ozil, who has been an outspoken critic of China’s Xinjiang policies. This led some Arsenal fans to conclude that Ozil was dismissed because of his outspoken statements about Uyghursm whom he called “warriors who resist persecution.”

Women stand outside next to binders with files on 5,000 people missing in Xinjiang, demanding answers from the consulate about their families. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

There also continues to be widespread vocal opposition in the Turkish parliament, particularly among the ruling party coalition of Turkish nationalists and religious conservatives who are supportive of the Uyghurs. Members of other parties in the opposition such as Özgür Özel have made recent statements demanding the Turkish government clarify its stance on the issue.

Dozens of Uyghurs continue to protest in front of the Chinese consulate but to no avail. Many there express gratitude for the long refuge Turkey has provided them, and are reluctant to say anything negative, but the jury is still out on how long that goodwill can last.

“We do not direct our ill will towards Turkey,” a mother holding up a sign of her missing family members tells me. “But the space for us is shrinking here.”

They leave me with a hand on their heart, a traditional greeting, and a farewell.

A woman protests holding a sign saying, “Where is my husband?” She believe he has been in an internment camp for years in Xinjiang. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

[ad_2]

Source link