[ad_1]

Nurse Modesta Littleman vaccinated patient Peter Sulewski in late January, on the first day of vaccinations at a clinic run by Health Care for the Homeless in Baltimore.

Yuki Noguchi/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Yuki Noguchi/NPR

Nurse Modesta Littleman vaccinated patient Peter Sulewski in late January, on the first day of vaccinations at a clinic run by Health Care for the Homeless in Baltimore.

Yuki Noguchi/NPR

Peter Sulewski spent nearly four years roving through Baltimore’s homeless shelters, and saw the toll it takes on health — even without the added threat of COVID-19.

“I’ve seen people freeze to death out there,” says Sulewski, whose home burnt down six years ago. At the same time, he says, “I would hate to be in a shelter during a pandemic. You’re walking through doorways at the same time with people who share the same bathroom that, you know, nine or 10 other people might be using.”

People experiencing homelessness are especially vulnerable to disease and often live in close quarters; reaching them for COVID-19 vaccination is crucial, public health officials say, yet also presents some unique challenges. Addresses and phone numbers change constantly. Few of the people affected have reliable Internet access.

Also, the pandemic put a halt to many mobile clinics and other outreach efforts to homeless encampments; in the meantime, patients scattered, or avoided the clinic for fear of infection.

“If they’re experiencing homelessness, all bets are off,” says Kevin Lindamood, CEO of Health Care for the Homeless in Baltimore, a community health clinic that treats 10,000 patients a year and recently started patient vaccinations. “It’s incredibly hard to reach people even in non-COVID times.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this month urged vaccination at soup kitchens and shelters.

But the pandemic curtailed many visits to homeless encampments and other outreach activities by his organization, Lindamood says. The Baltimore mobile clinic run by Health Care for the Homeless — part of a national network of 200 similar clinics — will resume service in coming weeks. But for now, staff are trying to contact eligible patients in their database.

As the clinic’s first day of vaccinations got started in late January, available slots were getting snatched up by eager patients who, like Sulewski, waited in a lobby with chairs lined up in a checkerboard pattern. Simply catching the bus to get vaccinated had meant risking infection, he told NPR. “The people are like packed like sardines and three quarters of the bus with no masks — that was a scary experience.”

At age 66, he now lives in an apartment, but still feels his health is fragile; he limps from arthritis, and has urinary problems.

In may places throughout the U.S., vaccines are in short supply. But some states, including Maryland, prioritized homeless populations because someone without adequate housing tends to have other conditions that make them especially vulnerable to disease.

Rolling out vaccine nationally is already complicated. But Lindamood says homelessness adds to those headaches, like coordinating with clients to get a second booster shot, four weeks after the first dose.

“Four weeks from now — that can seem like in an eternity if you don’t know where you’re going to be tomorrow, if you’re living transiently from place to place,” Lindamood says.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 isn’t even the gravest health threat to most of his clients. Among the clinic’s 157 patients who died last year, he says, COVID-19 was not the leading killer.

“People were already dying from hypertension and diabetes, addiction and mental illness,” Lindamood says.

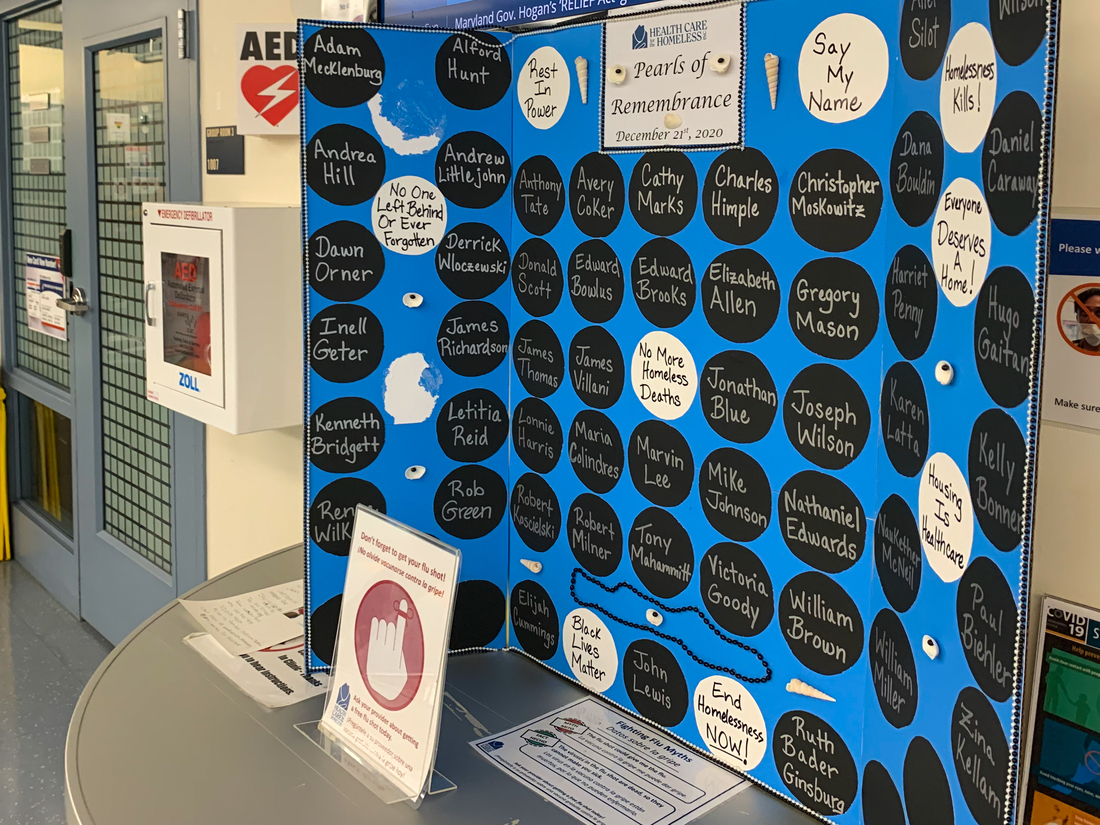

A poster memorializes recently deceased clients of Health Care for the Homeless in Baltimore. Among the clinic’s 157 patients who died last year, says CEO Kevin Lindamood, COVID-19 was not the leading killer. “People were already dying from hypertension and diabetes, addiction and mental illness.”

Yuki Noguchi/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Yuki Noguchi/NPR

A poster memorializes recently deceased clients of Health Care for the Homeless in Baltimore. Among the clinic’s 157 patients who died last year, says CEO Kevin Lindamood, COVID-19 was not the leading killer. “People were already dying from hypertension and diabetes, addiction and mental illness.”

Yuki Noguchi/NPR

Race and immigration status can signify other barriers, because people in marginalized communities tend to mistrust medical care, and therefore might be hesitant to get the vaccine. About 85% of clients at the Baltimore clinic are Black or members of another disenfranchised minority group. Women, children, and undocumented immigrants make up a growing percentage of the patient base. “COVID-19 is layered over all of those pre-existing emergencies,” he says.

Joseph Taylor is 72 and says seeing friends and family suffer or die put the fear of COVID-19 in him. “I’m not easily frightened, but I couldn’t wait for the vaccine,” he says.

Taylor is diabetic, hypertensive, and has a history of heart and lung problems — conditions that moved him to the front of the vaccine line at Health Care for the Homeless. He started getting health care there a while back, following a stint in prison.

Eager patients like Taylor easily fill the 10 slots on the first day of vaccination. To start, the clinic is only administering one vial of the Moderna vaccine, which contains 10 doses.

Finding patients, managing the flow of traffic and matching patients to doses will become more difficult as vaccination ramps up, says Catherine Fowler, a registered nurse who heads the clinic’s nursing team.

A big reason is the vaccine itself, which expires six hours after a vial is punctured, she says. So patients must be managed in groups of 10, and when there are cancellations or no shows, spare doses must quickly be redirected to other patients.

“You need to have a nimble system to then find more people and get those 10 doses into arms,” Fowler says. But that, again, raises the communication and transportation hurdles for those without stable homes.

So Fowler keeps tabs on other patients in the building, or nearby. As she explains that process, her phone pings with a text message from a colleague saying, “I know a patient who can be here in five minutes if needed.”

Meanwhile, back in the lobby, Peter Sulewski sits socially distanced from other patients who are being monitored for 15 minutes after receiving their shot, to make sure they can be easily treated if they develop an allergic reaction, which is rare.

“I feel relieved,” Sulewski says, motioning to his left shoulder. His attention is already shifting to the other people he wants to follow suit. He worries they won’t.

He says his girlfriend, for example, told him she won’t get the vaccine because she’s afraid of needles. “That’s why,” Sulewski says, “I think COVID-19 might be here to stay.”

[ad_2]

Source link