[ad_1]

On March 1, 2020, the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines arrived in the Philippines – for many, representing the long-awaited the light at the end of the tunnel. However, as vaccine confidence plummets in the country, the end of the pandemic remains elusive, with knock-on effects for the economy, which used to thrive on consumption and investment confidence.

The success of a vaccination campaign as a public health intervention hinges upon individual action to achieve collective or herd immunity. This might as well be called social solidarity, something the Philippines once held as a matter of pride. In fact, in 2015, the country showed some of the highest rates of vaccine confidence in the world, and while many countries struggled with anti-vaccination movements, the Filipino’s compliance with childhood vaccinations remained laudable.

This changed drastically when the Dengvaxia controversy erupted, and further intensified under the Duterte administration. The initial implementation of a school-based anti-dengue immunization program in three regions in the Philippines began in 2016 under President Benigno Aquino III, led by the Department of Health. A year after the implementation of the program, Sanofi, the pharmaceutical company that produced the dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia), released findings that it caused an increased risk of severe dengue for initially seronegative patients. Subsequently, several reported deaths allegedly linked to Dengvaxia fed widespread media coverage of allegations that the vaccine was to blame, even as many scientific assessments questioned these claims. The allegations of corruption also allowed some to “weaponize” Dengvaxia – targeted initially at leaders from the Aquino administration, and later including some in the Duterte administration as well.

Frenetic political noise trumped science-based views, and the highly politicized debates around Dengvaxia eventually led to the suspension of the vaccination program in the Philippines in December 2017. While the Philippines banned the use of Dengvaxia, other countries including Brazil, Singapore, Thailand, and United States authorized its use based on scientific evidence that with proper screening procedures, the vaccine can reduce severe dengue by up to 70 percent. In 2019, the World Health Organization added Dengvaxia to their model list of essential medicines recommended for use among high-risk populations.

Attacks on Dengvaxia still continue well into President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration. As late as last November 2020, already during the pandemic, the Public Attorney’s Office reported to media that 99 relatives of Filipinos who allegedly died from severe dengue due to Dengvaxia filed cases against the sitting and previous health secretaries, along with 39 other government officials.

Vaccine Hesitancy: A Consequence of Politicized Public Health Controversies

As the Dengvaxia controversy raged and received widespread coverage in mainstream and social media, vaccine confidence among Filipinos hurtled catastrophically. Back in 2015, 93 percent of Filipinos strongly agreed that vaccines were important. This fell steeply to just 32 percent by 2018. Compliance with childhood vaccinations like the measles vaccine dropped from 88 percent in 2014 to a devastating 55 percent in 2018. Measles cases rose by almost 2,000 percent from 2017 to 2019, and 632 measles related deaths were reported in 2019 alone.

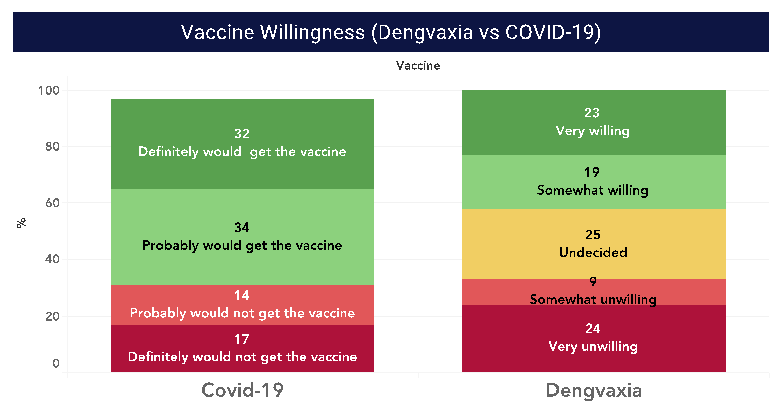

The consequence of the politicized Dengvaxia controversy on vaccine confidence is unmistakable, and is likely affecting the country’s COVID-19 vaccination prospects. In a nationally representative survey by the Social Weather Stations in September 2020, one-third of those surveyed demonstrated COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and only 66 percent of Filipinos were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine. (See Figure 1 below.) Similarly, in a survey done by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Facebook from July to November 2020 which included 22,000 adult Filipinos, only 61 percent of the respondents expressed willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Meanwhile, in a survey of 600 respondents from Metro Manila done by the University of the Philippines in December 2020, only 25 percent were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine, 28 percent refused the vaccine, and 47 percent were undecided.

Figure 1: SWS Survey Data on COVID-19 and Dengvaxia Vaccine Willingness

Ateneo Policy Center analysis using data from Social Weather Stations. Numbers are rounded and thus may not add up to 100 percent.

It is important to note that these surveys were conducted before the government expressed (and was criticized over) its preference for the Chinese-made Sinovac vaccine, despite significantly lower efficacy rates and its less competitive price point. There were again allegations of corruption and speculations that the preference for Sinovac was politically motivated. It is possible that vaccine hesitancy is much more acute for Sinovac. In fact, in a survey conducted in late February 2021 only 12 percent of the Philippine General Hospital health personnel were willing to receive the Sinovac vaccine, as most sought further appraisal of that particular brand by the Health Technology Assessment Council. The message of these health professionals is clear: They trust and want scientific bodies, not politicians, to be making the technical public health decisions. Meanwhile, the Chinese manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines are not doing themselves a favor if they cannot practice greater transparency in their vaccine testing data – and even international experts are challenging them to start building trust through transparency.

Struggling to Build Back Trust During COVID-19

The Philippines’ vaccine czar, ex-General Carlito Galvez, publicly lamented how the Dengvaxia controversy complicated negotiations with pharmaceutical companies supplying COVID-19 vaccines. Wary of being involved in similar political controversies, these companies first sought indemnity agreements before making deals with the Philippines.

As if the Dengvaxia controversy did not complicate the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out enough, there was the recent brouhaha over the admission of some public sector officials, notably the Presidential Security Group and the president’s special envoy to China, that they had already been vaccinated using unregulated and as yet unapproved vaccines from China as early as September last year. This likely set back trust-building, and has in fact exposed how government protocols are flaunted by some officials in power. Now, that the Sinovac vaccine has arrived in the country, the population is divided about whether or not to opt in. Duterte may have further fanned the flames of vaccine hesitancy when he refused to receive the Sinovac vaccine, stating that he prefers another brand.

The country’s policymakers and leaders must not forget that they are dealing with a population that is still shaken from the events surrounding the Dengvaxia controversy. Because of its poor handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and the line-jumpers in the administration that saw fit to publicly boast their ability to vaccinate themselves with a smuggled and still unapproved Chinese vaccine, it seems inevitable that public trust in the government’s vaccination program is at an all-time low.

Many will argue that politics is intertwined with public health. If that be the case, it must not compromise nor encumber public health, and instead support it. In this pandemic, where the vaccine is the most viable solution, the government must buttress the COVID-19 vaccination program by rehabilitating what is left of the public’s trust through consistent messaging, transparency, and respect for science. When Filipinos can again trust that the government will act in good faith for the safety and well-being of the people – that they are on the same side – social solidarity becomes conceivable, and responding to that individual call for action essential for collective immunity might again become more straightforward for Filipinos. Perhaps only then can the end of the pandemic be achieved.

This article draws from a recent study, “Public trust and the COVID-19 vaccination campaign: Lessons from the Philippines as it emerges from the Dengvaxia controversy” by C. Alfonso, M. Dayrit, R.U. Mendoza and M.A. Ong (2021), Ateneo School of Government and Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health.

Cenon Alfonso, MD, is dean at the Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health.

Manolet Dayrit, MD, is adjunct professor and former dean at the Ateneo de Manila University School of Medicine and Public Health.

Ronald U. Mendoza, Ph.D., is dean at Ateneo de Manila University’s School of Government.

Madeline Ong, MD., is adjunct research faculty of the Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health.

[ad_2]

Source link