[ad_1]

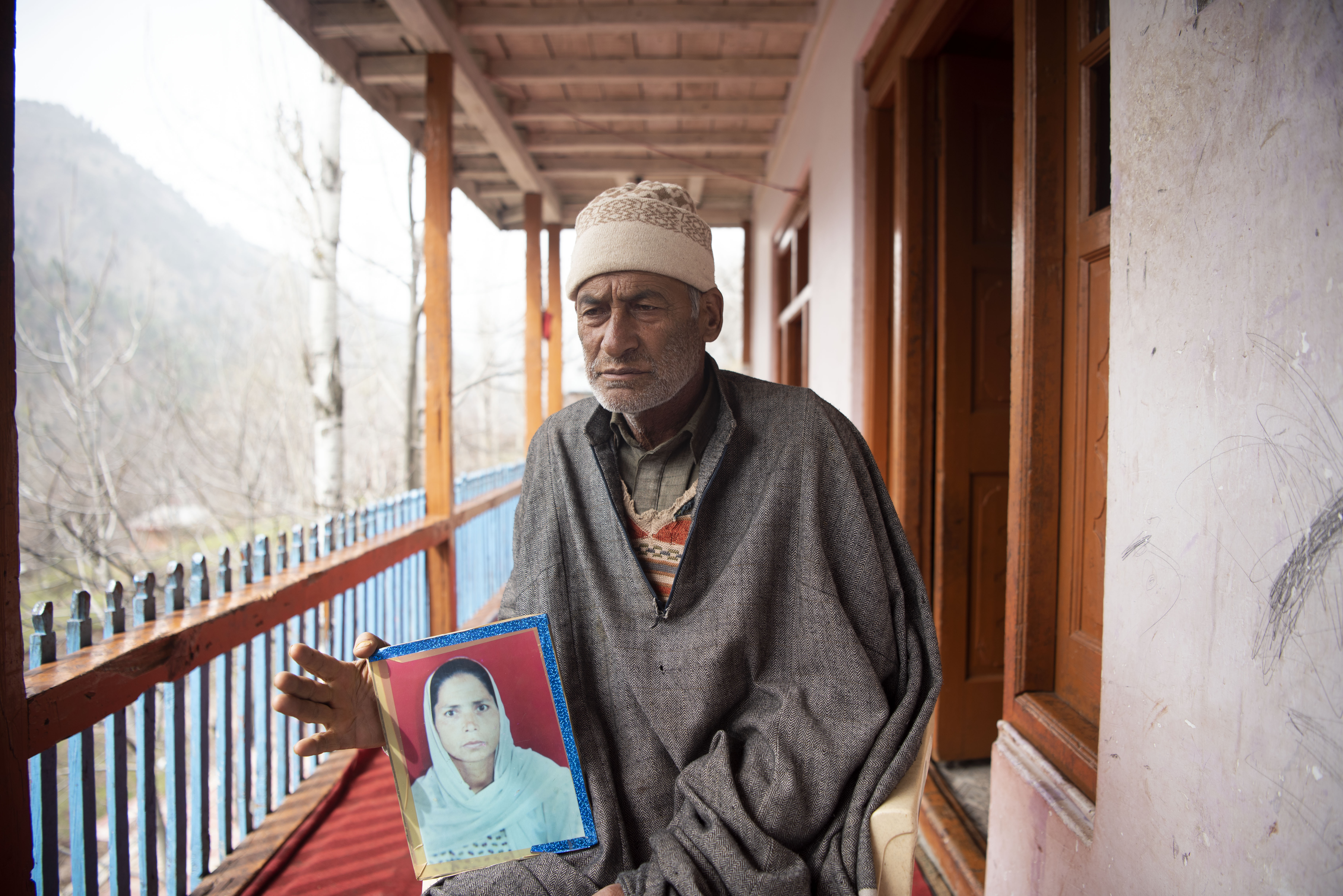

On the balcony of his rustic wooden house, which faces a mountain dotted with huts, bunkers, and mud houses, 65-year-old Ghulam Qadir Chalkoo points his frail finger toward the mountain top. Then his finger trails down, as if drawing a trajectory down the slope, cutting through the ridges, crossing waters, and ascending another mountain before it stops just below a deserted bunker near his home.

“There, right above this bunker, they fired a burst of bullets at my wife. It ripped apart her belly. She died there,” Chalkoo reminisces, his eyes blankly fixed at the spot.

This is Silikote, one of the last villages located at the Line of Control (LoC), the precarious line that runs through Jammu and Kashmir, dividing it between India and Pakistan. The two countries share a 3,252-kilometer border, 767 kilometers of which form the LoC that runs through Jammu and Kashmir.

The mountain Chalkoo that pointed at, within walking distance of his home, is the local site of the LoC, the de facto border. For several decades, the armies of India and Pakistan have been engaging in routine and constant violence along this dividing line: firing bullets, mortar shells, and at times missiles. In this day-to-day war, the villages sandwiched between the two armies have always paid a heavy price.

Chalkoo’s wife was killed in August 2003 when she was feeding the cattle. “Suddenly, there was a burst of fire. When I rushed to look for my wife, she was lying there, dead,” he tells The Diplomat. Chalkoo points toward a bunker atop the mountain facing his two-story house and says the bullets were fired from “there,” from the Pakistani side of the LoC.

Ghulam Qadir Chalkoo shows a photograph of his wife, who was killed in 2003 in cross-border firing. Photo by Haziq Qadri

The very location of Silikote and the adjoining villages has been made hazardous. Every house, every structure, and every movement is under scrutiny by the Pakistani Rangers across the border and by the Indian Army on this side.

The cluster of villages that borders the LoC is enclosed with a lengthy barbed-wire fence that runs from one mountaintop down the stream and ascends to the other mountaintop. A gate guarded by the Indian Army controls whoever enters and leaves these villages.

At the entrance, a lone sentry opens the gate and notes down every detail. He rings his commanding officer to decide whether we should be allowed to speak to the villagers. After several calls and back-and-forth, he asks us to be careful with our movements. “It’s calm as of now, but you never know,” the soldier tells us.

We ask him if he can point out for us a bunker of the Pakistan Army on the mountain. “I can’t point my finger, they will suspect something. It’s dangerous. Just look at those withered trees. There it is,” he says, guiding our gazes in the direction of the bunker.

That is how delicate and fragile the calm is in these villages.

For nearly three weeks now, Silikote has not rattled with gunfire, nor the tremors caused by the mortar shells. “It rains bullets otherwise. Living in these villages is like shrouding yourself every day. But it’s calm now. It’s such a relief,” Chalkoo says.

Chalkoo’s story is one of pain and misery. On November 1, 2001, the armies of India and Pakistan engaged in an intense firefight along the LoC. The two sides fired heavy ammunition, targeting bunkers and check-posts. When the firing started, Chalkoo’s son was heading to school. A mortar shell landed in front of him, tearing off his right leg.

Ghulam Qadir Chalkoo shows a photograph of his son, who lost his right leg after he was injured during cross-border firing in 2001. Photo by Haziq Qadri.

While the situation is relatively calm now and villagers are hoping against hope, there is a tangible and certain fear that the bullets and mortar shells might rain down again at any time. The line dividing arch-rivals India and Pakistan has never known true peace.

Both India and Pakistan claim Kashmir to be their territory and have fought three wars over it. The two countries each control two separate parts of it, divided along the LoC.

The last time the two neighboring countries made a peace pact and agreed on a ceasefire along the borders was in November 2003. It was a breakthrough in the relations between India and Pakistan: There was calm along the border, people started building their lives in these villages and, most of all, it paved the way for the opening of the Srinagar-Muzaffarabad and Poonch-Rawalkot routes, the opening for the first time of bus and truck services linking the divided halves of Kashmir. The ceasefire lasted for a few years, but it has been frequently violated by both sides since 2008.

In 2016, India-Pakistan relations took a turn for the worse after India claimed to have crossed the border clandestinely and destroyed “terrorist launchpads in Pakistan” following a deadly militant attack on an Army camp in Uri, North Kashmir, that killed 18 Indian soldiers. Since then, the violence along the LoC has intensified and turned more brutal.

In 2020 alone, as per the official statement of the two governments, the two armies violated the 2003 ceasefire 5,133 times, killing at least 50 civilians and 24 security personnel, wounding hundreds, and destroying several homes.

An abandoned house in Silikote village in Uri along the Line of Control. The owner of the house fled to a safer place due to the unabated cross-border shelling. Photo by Haziq Qadri.

More importantly, there has been an uptick in the violence along the Indo-Pak border since the Indian government abolished Kashmir’s special status and downgraded it into a federally-controlled territory, a move Pakistan strongly protested, saying any changes to the disputed territory violate the U.N. resolutions on Kashmir. Alone on the Indian side, according to the Indian government, 31 civilians and 39 security personnel have been killed in cross-border firing since the abrogation of Kashmir’s special status on August 5, 2019.

But now there is once again some hope. Top army officials of the two countries in February said in a joint statement they would abide by the 2003 ceasefire agreement. “In the interest of achieving mutually beneficial and sustainable peace along the borders, the two [Directors General of Military Operations of India and Pakistan] agreed to address each other’s core issues and concerns which have the propensity to disturb the peace and lead to violence,” reads a joint statement issued by India and Pakistan on February 25.

Ever since the two countries agreed on halting violence along the LoC, several families in Silikote that had fled the village to safer places are gradually returning. The elderly Mohammad Azam says he had fled to Uri, a town in the frontier district, after the shelling and firing in his village intensified a year ago. “Now I have returned, thanks to both the countries. Now we can breathe peacefully here,” Azam tells The Diplomat.

Mohammad Azam of Silikote is among the few families returning to their homes in villages bordering the LoC. Photo by Haziq Qadri.

Next to Chalkoo’s house is a school where classrooms are empty and no students can be seen. Two teachers – the entire staff – sit outside the school on a slope, basking in the sun. “There are no students. We just come here every day, hoping any student will turn up,” says Saima Chalkoo, one of the teachers.

But the return of the children, who have fled to safer places, depends on how stable the relations between the two countries remain. Saima recalls several incidents in which teachers had to rescue the kids from the school as the two armies traded bullets and mortar shells.

“There are times when we ask children to lie flat in the classrooms. Though that does not help, because if a shell lands on the school, it could cost many lives. It’s just not safe to be in this building,” Saima says, pointing toward the Pakistani army bunkers directly staring at the school building.

Her colleague, Rubeena Akhter, shows us the houses adjacent to the school that have been damaged by the shelling. “It’s not safe to be anywhere here,” she says.

Rubeena recalls how a few years ago they had to rescue children from the school and rush them out of the village to a safer place as the two armies showered each other with bullets. “It’s a run for [your] life. You know for certain you might get hit, but you have to run. That is how life is here,” she says.

But with the reaffirmation of the 2003 ceasefire, the two teachers hope the school will witness some activities again.

The desolate Tilwadi village along the Line of Control is witnessing a gradual return of people who had fled to safer places due to the unabated cross-border shelling. Photo by Haziq Qadri.

An arduous trek down the mountain leads to another border village, Tilawadi, where mud-brick houses are pockmarked with bullets; several houses bear damage caused by heavy mortar shells.

The village, calm after several years, is now witnessing the return of several families hoping to restart their lives, or to rebuild what has been lost.

“We hope to repair our houses and make them stronger and safer. But most of all, we hope to live in peace after a long time,” says 30-year-old Bilal Ahmad Khan. Khan says abandoning their homes every time there is shelling across the border makes them homeless and dispossesses them of everything they hold dear.

It’s not only the homes and possessions that they leave behind, Khan says. The cattle die, either from starvation or bullets. “And if fate is unkind, they bleed to death when entangled in a barbed fence,” he says.

While there is hope, there is skepticism as well. India and Pakistan have fought three wars over Kashmir since the two countries became independent in 1947; there has been a full-blown armed insurgency in Kashmir, supported by Pakistan; and at the diplomatic and political levels, both countries have over the years engaged in intense verbal spats. Moreover, ever since the right-wing Hindu nationalist BJP, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, came into power in India, the ties between the two nuclear powers have deteriorated. In such times, the ceasefire is looked upon with uncertainty.

“The ceasefire agreement agreed between [former Indian Prime Minister] Vajpayee Ji and [former Pakistani President] General Musharraf lasted for a long time because it was followed up with the dialogue process. [If] this ceasefire, too, is not followed with dialogue with Pakistan and the people of Jammu and Kashmir, it will be too fragile to last,” Mehbooba Mufti, former chief minister of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, told The Diplomat.

The timing of the ceasefire agreement is also interesting. Mufti says the narrative of confrontation between India and Pakistan “not only suits the BJP but also gives it huge dividends in elections.”

Mufti believed pressure mounted by the newly elected U.S. President Joe Biden on the two countries helped lead to the current peace.

“So left to the central government, there seem to be fewer chances of any reconciliation between the two sides. I think the U.S. pressure may have played its part in this ceasefire,” Mufti says.

A view of Pakistan-administered Kashmir from Silikote village in Uri. Photo by Haziq Qadri.

Pessimism over the ceasefire aside, the villages along the Line of Control are coming back to life gradually and everyone is holding on to whatever little hope they have left. For now, the quiet slopes of these villages, the occasional mooing of the cattle, and the chatter of the villagers signal hope. It’s different from a constant rattle in the air, so constant that sometimes the two armies would shower bullets at each other over the slightest provocation, like if a wicket fell or a batsman hit for a six during an India-Pakistan cricket match.

“But peace is fragile,” a senior army official stationed at Silikote says, as he guides us towards the exit.

[ad_2]

Source link