[ad_1]

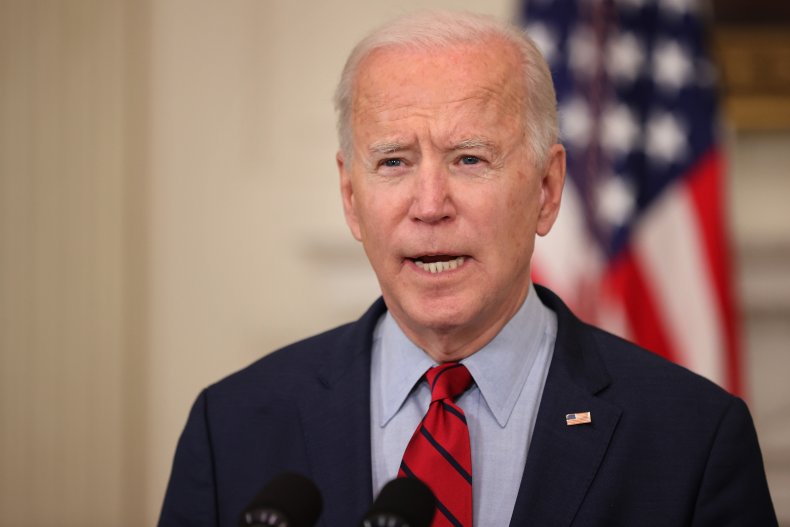

Reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran is supposed to be one of President Joe Biden’s landmark foreign policy achievements.

A return to compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal would, according to its supporters, end the immediate threat of a nuclear-armed Iran and take the heat out of simmering tensions across the Middle East, allowing Biden to refocus U.S. foreign policy on its next great challenges, especially China.

The Biden administration and President Hassan Rouhani’s government in Tehran both want to revive the JCPOA. But their window is closing. The U.S. and Iran have spent the first months of the year stuck in a stalemate, waiting for the other to blink first.

Rouhani’s term will end in June when Iranians head to the polls. The country’s ruling clerics are all but certain to pave the way for a hardliner to become the next president, perhaps even a candidate drawn from the ranks of the zealous Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

As Iranian activity slows during its Nowruz new year holiday, there are no signs of an imminent breakthrough between Washington, D.C. and Tehran. After the holiday, the presidential election campaign will kick into a higher gear.

Less than three months into his term, Biden might have already missed his shot.

“I have a hard time believing that if Rouhani is gone, the JCPOA is going to be viable,” said Sina Toossi, a senior research analyst at the National Iranian American Council.

Rouhani has “fought tooth and nail” to keep the deal alive despite domestic skepticism, Toossi added, but his options are almost exhausted. “Rouhani’s hands are largely tied, he’s a true lame duck,” he said.

Rouhani and his Foreign Minister Javad Zarif have weathered much domestic criticism of the JCPOA and recently had to defend their desire to revive the accord to the conservative-dominated parliament.

With the end of the Rouhani era in sight, the momentum is with the conservatives. Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 and subsequent sanctions campaign vindicated those Iranians who were skeptical of engaging with the U.S. in the first place.

The assassinations of Major General Qassem Soleimani and nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh are further evidence for the skeptics that the U.S. and its allies cannot be trusted to engage in good faith. Deterrence is the order of the day, they say, at the heart of which could sit a nuclear arsenal.

Above all other concerns sits the security of the Islamic Republic. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is 81 and unwell. Several past reports of his imminent demise have proved unfounded, but Khamenei knows his time is nearly up.

The regime has resorted to mass violence to suppress protests in recent years. At the end of 2019, it killed about 1,500 people in order to put down unrest sparked by a new fuel tax. Tehran has also periodically throttled internet connections to try to stem the spread of public anger at state corruption and brutality. Anti-regime sentiment in Iran is real and widespread, though there is still no realistic political alternative to marshal that anger.

A conservative president—in Khamenei’s words a “young and hezbollahi” (ideologically hardline) figure—would ensure a smooth transition to the next supreme leader. As Behnam Ben Taleblu, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said, this election is “all about Iran’s most important voter, which is Khamenei.”

Among the candidates vying to be Khamenei’s chosen man is Hossein Dehghan, a former IRGC air force brigadier general who served as Rouhani’s defense minister. Another is Parviz Fattah, a former IRGC member who heads the Mostazafan Foundation charity, which was recently put under sanctions by the Treasury Department.

A third is one of the IRGC’s youngest generals, Saeed Mohammad, a 53-year-old highly educated technocrat who until recently was the commander of the guard corps’ Khatam-al Anbiya engineering operation.

It remains to be seen whether an IRGC or conservative candidate would—with approval from Khamenei—still pursue JCPOA revival. Iran knows it needs relief from U.S. sanctions,and hawks point to suspicions of secret nuclear sites in Iran as evidence that Tehran might continue advanced research nuclear even under a resurrected deal.

But a conservative president is unlikely to prove an easier negotiating partner for Biden. There would be a “constellation of diplomacy skeptics” in such an administration, Taleblu said.

This might make escalation more likely, whether through increased regional proxy attacks, covert actions or expanded nuclear activity. Then, said Toossi, “America is going to be left to choose between either launching military strikes, or it’s going to come to the negotiating table and negotiate a new deal with the hardliners.”

STR/AFP via Getty Images

For Iran hawks in Congress, the identity of Iran’s next president is largely irrelevant. Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) said the ayatollah-controlled regime would “continue seeking the destruction of the United States regardless of the outcomes of their sham elections.”

Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) dismissed the elections as “a farce controlled by the Iranian regime,” one that “violated Obama’s deal, funnels weapons to terrorists, takes Americans hostage, and brutally represses the Iranian people.”

Rubio added: “The U.S. should continue to put maximum pressure on the Iranian regime until it halts its malign and destabilizing behavior. It is in the interest of our nation’s security to accept nothing less.”

One congressional GOP staffer told Newsweek that Republicans on Capitol Hill believe Biden is fully committed to an Obama-style approach to Iran—prioritizing a deal with Tehran over maximum pressure.

Some believe Biden is genuinely trying to constrain Iran, but others fear the president will embolden the regime in its malign regional activities. Most will likely continue to defend maximum pressure and remain skeptical of diplomacy.

Characterizing Biden’s approach as “reckless,” the congressional staffer said: “The Iranians remain a violent terrorist expansionist regime.”

Biden’s public lack of progress on the JCPOA is concerning supporters of the accord, especially after the president’s special envoy on Iran, Rob Malley, said the administration would not let the June election dictate the speed of talks.

Senator Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) said “the window for meaningful diplomatic engagement on Iran’s nuclear activities is narrowing.” Van Hollen added that he “fully” supported Biden’s so far unsuccessful push for a mutual return to compliance by both sides ahead of the “likely” election of a hardliner president. “Time is of the essence to constrain Iran’s nuclear program through smart diplomacy,” Van Hollen said.

Van Hollen and other Democrats have blamed Trump for the state of U.S.-Iran relations.

“The Trump administration’s reckless foreign policy moves isolated us from our allies and allowed Iran to ramp up its uranium enrichment activities, reducing its breakout time from more than a year to a matter of months today,” he said, adding that Iranian hardliners had been “buoyed by the Trump administration’s feckless strategy.”

If Biden does miss the Rouhani window, Iran’s next president will try to present the U.S. with a choice between “a regional war that’s going to be very costly, or a new nuclear deal that is probably less strong than the JCPOA,” Toossi said.

The head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Rafael Grossi, has also acknowledged that the election will have a bearing on what role his inspectors play. Asked about the election, Grossi told Newsweek on Tuesday: “It’s a factor.”

“I would say that in whatever scenario—hardliners, softliners, any liners—we have to solve this issue, one way or the other,” Grossi said. “I hope it can be done and I think it’s in everyone’s interest and everyone’s advantage to come to a solution to this problem, and I think the Iranians recognise this themselves.”

There is still hope for JCPOA progress in the coming months, even if both sides are sticking to their guns—at least publicly—and denying there has been any behind-the-scenes contact. Any success would come despite conservatives in both countries pushing to kill the deal, with the help of U.S. allies in Israel and Saudi Arabia.

“There’s so much pressure here,” Toossi said, “from Congress, hawks, hawkish organizations, pro-Israel groups and lobbies.”

“I think Biden is trying to navigate this pressure,” he added. “They’re trying to placate a lot of these people in Congress. They ultimately do want JCPOA return, I believe, but the way they’re going about it, they risk losing this opportunity.”

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

[ad_2]

Source link