[ad_1]

We flopped with the climate targets set in Kyoto. We crashed and burned after Copenhagen. And we seemed destined to suffer the same plight after Paris.

Now Canada is trying again.

This time it’s happening at a two-day virtual meeting of world leaders hosted by the new U.S. administration, where on Thursday Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will set a new Canadian emissions target.

We already have the basic gist of what Trudeau will announce: it was hinted at in this week’s federal budget, though the government says Trudeau will go a step beyond that.

With carbon tax-and-rebate policies already in place, and new funding for home retrofits and green technology, the government said Canada can not only meet the Paris target — but go even further and slash emissions at least 36 per cent by 2030.

Is this real? Is it possible that after making empty promises in far-flung destinations around the world, the place where Canada will actually announce a climate target it has a hope of meeting is an online meeting?

A climate economist at the University of Alberta, Andrew Leach, called that 36 per cent estimate from the budget realistic, albeit not guaranteed.

“It’s in the ballpark,” Leach said.

Trudeau is expected to push that further, according to Radio-Canada, and announce a targeted cut exceeding 40 per cent; Leach called that more difficult, and said it will depend on oil prices.

Beyond Canada, this meeting is intended by Biden as a turning of the page on global co-operation and competition.

A lot has changed since the Paris Agreement was forged in 2015: the U.S. left and came back, it’s had two presidents with decidedly different views on climate change, there’s an escalating rivalry with China, investment in clean technology has boomed — and the climate outlook has worsened.

Whether this next chapter of global climate policy is more successful than the last one may hold considerable stakes for the planet.

The global picture: Not good

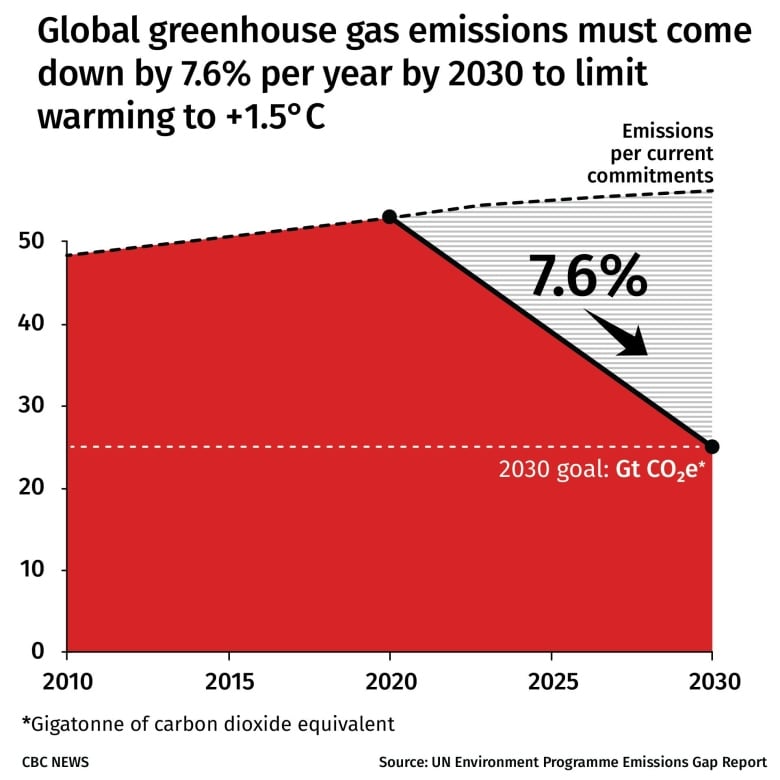

With emissions still drifting up, the United Nations has described the 2010s as a lost decade and said the planet has already warmed 1 C above pre-industrial levels.

It says 1.5 C in warming is likely, and 2 C will happen without a 25-per cent emissions cut this decade — meaning deeper damage to ecosystems and food access, worse storms, more animal extinctions and catastrophic ocean acidification.

The new U.S. administration has called climate change a top priority.

President Joe Biden is back in the Paris accord, has signed executive orders, and has proposed expensive clean-tech legislation.

Now he’s called other countries to this meeting to pressure them to do more.

“The expectation for all countries is that the ambition has to be increased immediately,” a senior Biden administration official told reporters in a background briefing Wednesday.

“It’s not, I think, a luxury that we’ve got to wait a decade before we start.”

Biden reportedly intends to announce a 50-per-cent emissions cut for the U.S. by 2030, which is nearly double the target announced by former president Barack Obama. Biden’s goal would represent a serious acceleration for his country, which so far has managed to cut carbon emissions about one percentage point per year since 2005.

What countries are announcing

Whether Biden’s big promises on the global stage are backed up by results at home will partly depend on whether the U.S. Congress passes his green-infrastructure plan.

Meanwhile, other countries are upping their commitments.

The European Union has announced plans for a 55 per cent emissions reduction from 1990 levels by 2030, after having already cut emissions nearly a quarter.

The U.K.’s emissions cuts have been even more aggressive and this week it set a new target of 78 per cent in reductions by 2035 from 1990 levels.

A major challenge for Canada, unlike those entities, is the significance of oil and gas production in its economy; fellow oil producer Norway, for example, has been less successful than its regional neighbours in cutting emissions.

A superpower rivalry is another emerging dynamic.

Turning climate into a modern-day ‘space race’

Fifty years after the U.S.-Soviet space race, Biden administration officials are casting this moment in similar terms, as a chance for two adversaries to compete on the battlefield of scientific discovery.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken gave a speech this week that cast the climate issue as a sprint against China — to fund, invent, and ultimately sell clean technology.

“Right now, we’re falling behind,” Blinken said.

“China is the largest producer and exporter of solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, electric vehicles. It holds nearly a third of the world’s renewable energy patents. If we don’t catch up, America will miss the chance to shape the world’s climate future in a way that reflects our interests and values. And we’ll lose out on countless jobs for the American people.”

China, for its part, is at a crossroads in its climate policy.

On a per–capita basis, the average Chinese person still doesn’t pollute nearly as much as a Canadian or American, but its national emissions have exploded.

In total volume, China is single-handedly responsible for half the world’s growth in carbon emissions since 2005, as hundreds of millions of its citizens join the global middle class, and has surpassed the U.S. as the top emitter per year.

Yet it’s not just building new coal plants.

At the same time, China has become a world-class inventor, producer, and exporter of clean technology, and it enters this summit having already promised to have emissions peak by 2030.

A former official in the Trudeau government says this is the story to watch at the summit: the U.S. and China turning clean technology into a lucrative contest.

“The lens to see the climate issue through has changed,” said Gerald Butts, now a vice-president at the political-risk consulting firm the Eurasia Group.

“[It’s gone] from multilateral co-operation, which it has been for the past 25, 30 years, and it’s now very much a theater for strategic economic competition.”

The most valuable car company in the world is now Tesla, its $684 billion market capitalization dwarfing numerous competitors combined.

Investors are now plowing money into these technologies while governments make plans to yank fossil fuels out of energy grids.

And neither China nor the U.S. want the other leading these fields, says Butts.

“The United States and China, in particular, are competing quite ferociously for who is going to have the most significant parts of the new energy supply chain.… And that’s created a much different dynamic which you’ll see on full display.”

[ad_2]

Source link