[ad_1]

On April 8, 1873, black residents in Baltimore gathered to pay homage to Johns Hopkins, a man with just months of life remaining who planned to create an orphanage for black children and a hospital open to whites and blacks alike.

One speaker at the rally praised the businessman for distributing his fortune “for the relief of the colored man.” Another said Hopkins was guided by “the highest expression of the spirit of the age.” A third added, “Wherever the colored man may be, there will his name be known.”

A Johns Hopkins University investigation that labeled its own founder a slave owner has come under criticism.

Wikimedia Commons

Of course, that name is still well known, but now partly for the wrong reasons, after a report released by Johns Hopkins University last December seemed to have determined that its founder had actually been a slave owner. An 1850 census document listing Hopkins as the owner of four slaves served as the chief basis for that finding.

The report also found no evidence that Hopkins had been an abolitionist, or supported the abolitionist cause, as had long been believed, and that further research would consider what evidence, if any, showed he “held or acted upon antislavery or abolitionist beliefs.”

The response was immediate. “Johns Hopkins Reveals Its Founder Owned Slaves,” said The New York Times. “Johns Hopkins was a slave owner, university reveals,” said The Guardian of London. The Baltimore Sun concluded: “We now know that the story of the founder of Johns Hopkins University and hospital as abolitionist and staunch opponent of slavery was nothing more than a fairy tale.”

In The Washington Post, Martha S. Jones, the history professor who led the investigation, wrote that the university had confirmed that Hopkins owned slaves, adding, “The shattered myth of our university founder, long admired as a Quaker and an abolitionist, rattles our school community.”

The university called the findings preliminary and said more research would follow, but the verdict already appeared to be in: Johns Hopkins had been on the wrong side of history.

And with the census document serving as the proverbial smoking gun, no appeal of that judgment seemed likely.

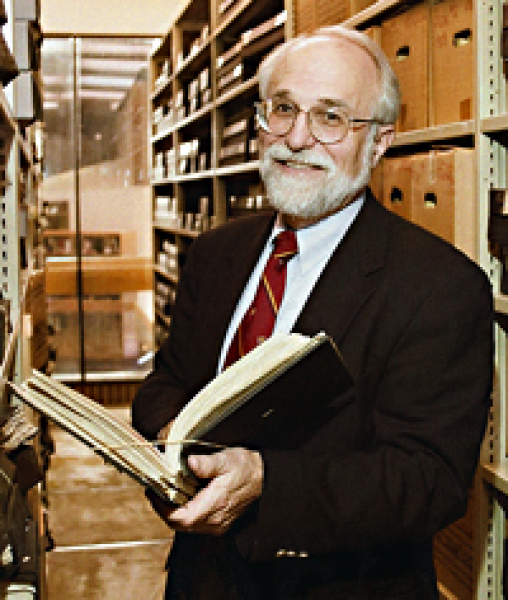

But a challenge has come forth, and from a most unexpected source: Ed Papenfuse, a retired Maryland state archivist who had first uncovered the census document in the course of his research and, indirectly at least, got the whole investigation started.

The university has gone “a bridge too far,” Papenfuse said, and has “basically taken seven documents or eight documents and argued that this proves a thesis, which it doesn’t.”

Retired Maryland state archivist Ed Papenfuse considers the slave owner designation “a bridge too far.”

Library of Congress

“You have to evaluate all the evidence before you can come to any dramatic conclusion that Johns Hopkins was a slave owner,” Papenfuse added. He and other skeptics of the university’s report have teamed up to post their own research into the matter at thehouseofhopkins.com.

After Papenfuse mentioned the census document last summer during a Zoom seminar on Baltimore history he taught at the university, one of the people listening in decided to track down the document herself. Soon, Jones was examining the matter as part of a broader exploration of the institution’s history of discrimination.

So what do the facts show? A deep dive into the historical record, coupled with interviews of Papenfuse and other historians, does cast doubt on some of the university’s findings. For example, three parts of the Hopkins story — his ties to abolitionists, his philanthropy and his Quaker faith — clearly suggest that he at least espoused antislavery views.

And despite the census document, a plausible argument remains that, as some writers had thought, Hopkins had not owned slaves, but instead actually freed some who had been owned by others.

The university made much of the role played by a grandniece’s fawning biography, published in 1929, in spreading the story of her uncle’s abolitionist past. But when Hopkins died at age 78 on Dec. 24, 1873, The Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser declared flatly that he had indeed opposed slavery — a stance that would have, for many Southerners, warranted the abolitionist label.

Hopkins had been “an antislavery man all his life,” the newspaper said. “His great wealth and high position saved him from the reproach that would have otherwise have fallen upon him in a community that had but little tolerance for the views which he entertained upon this subject.”

That reputation may have grown out of Hopkins’s associations with a number of prominent antislavery figures, most notably Elizabeth Janney, his first cousin, and her husband, Samuel M. Janney, who are remembered today as leaders of a Quaker “nest of abolitionists” in what is now Lincoln, Va.

Samuel M. Janney, married to Hopkins’s cousin Elizabeth Janney, was a prominent antislavery activist.

Private Collection via LincolnQuakers.com

In 1856, Samuel Janney and Hopkins joined the board of Myrtilla Miner’s School for Colored Girls in Washington, which had opened five years earlier despite the black leader Frederick Douglass’s worries that doing so would be “reckless, almost to the point of madness.”

Rocks, both literally and figuratively, would be hurled Miner’s way. On May 6, 1857, a former Washington mayor, fearful the school’s planned expansion would flood the area with black students and their families, took aim at not just Miner but at the powerful men backing her, too.

In a letter published in The National Intelligencer, the former mayor, Walter Lenox, accused the school of secretly aiming to abolish slavery, said it educated blacks “far beyond their political and social condition” and warned that “tumult and blood may stain” its future.

Lenox listed the names of all 10 board members, which included such abolitionists as the preacher Henry Ward Beecher and the editor Gamaliel Bailey. (Beecher’s sister, the “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” author Harriet Beecher Stowe, was also a key backer of the school. The indomitable Miner’s story is told in Michael M. Greenburg’s book, “This Noble Woman.”)

Years later, Abraham Lincoln’s abolitionist Treasury secretary, Salmon P. Chase, seemed to offer high praise for Hopkins. After Chase attended an 1863 gathering of businessmen hosted by Hopkins, he wrote in his diary that those on hand were all “earnest Union men. And nearly all, if not all, decided Emancipationists.” (Maryland would not end slavery until late 1864.)

Hopkins eventually became “sort of persona non grata in Baltimore because of his support of Lincoln, and for antislavery politics,” said Manisha Sinha, a University of Connecticut history professor and author of “The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition.”

Sinha said Hopkins reminded her of many Southern Quakers who wanted no part of Northern abolitionism, but who still opposed slavery, and also of figures like Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and Benjamin Franklin, who eventually got rid of their slaves and then “lent the prestige of their names to the antislavery movement.”

Facing Cultural Headwinds

Hopkins’s insistence that his fortune be used to benefit all Baltimore’s residents regardless of color was not always appreciated. That was the case with his hospital plan, despite assurances by his trustees that “a brick wall” would separate black and white patients.

An item in the Baltimore Sun on Sept. 15, 1870, showed what Hopkins was up against.

White people, the article said, “no matter how grievously afflicted with poverty or disease,” would never consent to any arrangements “which may tend to force them to accept social communion with the blacks as the consideration for their relief from inconveniences or discomforts resulting from that poverty or that disease.”

At Johns Hopkins’s insistence, the now world-renowned hospital that bears his name was founded to serve Baltimore’s black and white communities.

Wikimedia Commons

Because he succeeded in “compelling assent” to his plan, The Baltimore American said, history could remember Hopkins as a courageous benefactor “who encountered a mighty prejudice and conquered it.” Upon his death, Hopkins would leave $7 million (worth $150 million today) toward the hospital and university that bear his name.

Part of that money would be used to create the Johns Hopkins Colored Orphan Asylum, which would operate until 1917. (Hopkins, a bachelor, had long planned such an institution; in 1867, Samuel Janney wrote to his wife about a visit to Baltimore in which “cousin Johns” mentioned his plans for helping black children.)

If Hopkins’s abolitionist connections and his philanthropic efforts were at odds with what might be expected of a slave owner, his Quaker faith seemed even more out of place.

The Quakers, also known as the Society of Friends, had grown increasingly intolerant of members who clung to slave ownership (though some members still tried to evade the rules.)

Had Hopkins chosen to own slaves, his meeting (or congregation) would most likely have ousted him, said A. Glenn Crothers, associate professor of history at the University of Louisville and author of “Quakers Living in the Lion’s Mouth.”

“I just find it difficult to believe that Johns Hopkins could be a slaveholder and not have the local meeting take action against him,” Crothers said.

But, according to Papenfuse, Hopkins appeared to remain in good standing with his Orthodox congregation: In 1867, he helped fund a new meeting house. In the 1820s, though, he and one of his brothers, Mahlon, had been ousted from what would come to be known as a “Hicksite” Quaker congregation, for trading in “spirituous liquors.” (Both Orthodox and Hicksites opposed slavery.) In 1839, Hopkins’s brother Samuel was removed from his Quaker meeting for owning two slaves.

Some Quakers tried to purchase the freedom of slaves themselves, but that could be very difficult, not only financially, but because of laws designed to discourage manumission. In some cases, that meant Quakers trying to free slaves could be unable to relinquish ownership, at least in a strictly legal sense.

“There are times when Quakers technically would have legal ownership of enslaved people but they were not using them as slaves or were using it as a step toward getting them their freedom,” Crothers said.

Crothers pointed to the North Carolina Quaker organization, which retained ownership of hundreds of slaves it was working to free, because of difficulty in meeting state requirements. (One provision required proof that a slave had performed a “meritorious service.”)

In 1856, Samuel Janney faced a similar dilemma. In a letter sent to a fellow Quaker, he told of buying Jane Robinson and her daughter, Eliza, for what would be about $11,000 today.

“The freedom of the mother is to take place now & that of the child when she shall attain to 18 years of age,” he wrote. “If the manumission is recorded our laws will require the mother to leave the state in a year & the child when she attains to 21 years. If it is not recorded I shall have to stand in law as the master, legally, while they stay here.”

Janney, a Quaker leader and writer, said that more slaves could be freed, but many Friends just did not have the resources to help.

So did Janney ever ask his richest relative to help him free slaves? If so, no record of it has surfaced.

Aiding runaway slaves would have been an iffy proposition for law-minded Quakers, but paying to emancipate slaves did occur, says history professor A. Glenn Crothers.

Flickr

(There is disagreement over how much the Janneys and others of his faith might have helped fugitive slaves, but Quakers were generally very reluctant lawbreakers. And Crothers suggested that Underground Railroad stops are far more numerous in the popular imagination than they were in the actual past.)

Hopkins did buy one slave, The Baltimore American reported, but only “to make him free.” That man was believed to have been his longtime coachman James Jones, who was with Hopkins until the end and was awarded $5,000 (about $110,000 today) in his will.

The university also raised questions about two 1830s business deals involving Hopkins and his brothers in which “they expected to acquire enslaved people in satisfaction of debts.” But Papenfuse said it is not known whether any slaves were actually acquired that way, or what would have been done with them had that occurred.

On another of the university’s findings, that no evidence showed Hopkins was an “abolitionist,” there is no disagreement — if the report’s definition of the word is accepted as an adherent of “radical antislavery politics” who favored slavery’s “immediate and unqualified end.” But under that scholarly, “immediatist” definition, even Myrtilla Miner, who once waved a revolver to disperse a mob, and Samuel Janney, who was charged with inciting slave unrest, might not qualify. Abraham Lincoln would probably fall short too.

Without commenting directly on Hopkins, the Harvard history professor Tiya Miles noted that even antislavery businessmen who traded in cotton textiles would still have “participated in and propelled an unjust system.”

She said the aim in investigating past leaders is not to find a “gotcha” moment, but rather to reach “a better and deeper understanding of these figures, and through them, of society as a whole.”

And “new questions can be asked and new evidence might be found,” said Miles, author of “The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits.”

A Smoking Gun?

The biggest question remaining for Hopkins concerns that 1850 census document.

Papenfuse contends that the census alone cannot prove slave ownership. Free blacks unable to immediately produce papers proving their status could have been incorrectly recorded, he said, or slaves that Hopkins had simply hired, but did not own, could have been listed as belonging to him.

Crothers said Hopkins might have been engaging in “some kind of temporary arrangement in which he was holding these slaves as a step toward their freedom and trying to work around the law.”

Another expert who says that the census cannot prove slave ownership is David E. Paterson, who manages the online AfriGeneas Slave Research Forum. He said the slaveholder category in 1850 actually included “slave-hirers,” who may not have actually owned slaves. (The 1840 census, which showed one slave in the Hopkins household, had no ownership question.)

Papenfuse’s bottom line? It is unfair to accuse Hopkins of slave ownership until evidence is produced of “Hopkins literally being a slave owner or investing in the institution of slavery that way.”

Contactly recently, the university’s Professor Jones said that while she is open to evidence that Hopkins did not own slaves, there are strong indications that he did.

She added that she has not contended it was a certainty Hopkins had owned slaves.

Martha S. Jones, the history professor who led JHU’s examination of its founder’s past, says there is strong evidence he owned slaves, though not certainty.

Flickr

“The census enumerator certainly recorded Mr. Hopkins as a slave owner; whether the enumerator was incorrect, I cannot say,” Jones said. “I’m sure that is the question that many people are asking.”

But, she said she had also seen no information countering the conclusion that Hopkins had relied upon slave labor in running his household.

Regarding Hopkins’s faith, Jones said: “There were Quakers in Baltimore who were connected with the interests and liberations of black Americans. Mr. Hopkins has never been shown to have been among them.”

Partly because Hopkins left so few personal papers behind, the questions regarding his connections to slavery may never be resolved. Though he seemed to have espoused antislavery views, it remains possible that his good deeds and abolitionist connections merely camouflaged an unwillingness to give up the advantages of slave ownership himself.

Such a man, though, would hardly have been worthy of the praise awarded him by the black leaders who spoke at that rally in 1873.

One of those speakers in particular, the preacher and former slave J. Sella Martin, who had been sold a dozen times before finally escaping to freedom, would have been a most unlikely cheerleader for an ally of slavery.

Fourteen years earlier, in a speech given in Boston on the occasion of John Brown’s execution, Martin made clear his feelings on the subject.

“It is not an accident,” he said, “but a necessity of the system of slavery, that it should be cruel; and all its devilish instrumentality, and enginery, and paraphernalia must be cruel also. It is folly for us to talk about the slaveholders being kind. Cruelty is part and parcel of the system.”

Of course, Martin and the other speakers may have been misinformed about the man they were applauding. Or maybe they just knew more about the true character of Johns Hopkins than we do today.

Steve Bell is a senior staff editor for The New York Times.

[ad_2]

Source link