[ad_1]

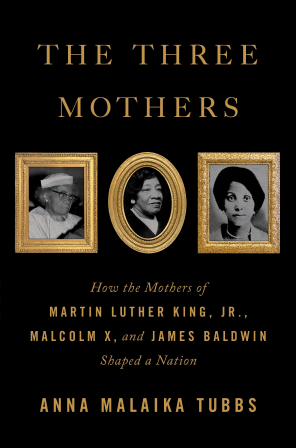

Photo courtesy of Anna Malaika Tubbs

The names Berdis Baldwin, Louise Little, and Alberta King might not spark instant recognition. But

they should. They are the women who raised the most prominent civil rights activists in American history: James

Baldwin, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

-

Anna Malaika Tubbs

Anna Malaika Tubbs

the three mothers

Bookshop, $27SHOP NOW

Gates scholar, sociology PhD candidate, and author Anna Malaika Tubbs wrote The Three

Mothers to piece together these women’s distinct yet intersecting stories. She explores our tendency to

understand women through the lens of the men in their lives, rather than seeing them for themselves. At the same

time, The Three Mothers is a poetic celebration: of Blackness, womanhood, and how mothers shape the world

by shaping their children.

In this excerpt from the book’s introduction, Tubbs reflects on what makes The Three Mothers

such powerful and personal work.

From The Three Mothers

Writing about Black motherhood while becoming one gave me a much deeper perspective than I had before. As my own life

and body transformed, it became even more important to me to tell Alberta’s, Berdis’s, and Louise’s stories before

they became mothers. Their lives did not begin with motherhood; on the contrary, long before their sons were even

thoughts in their minds, each woman had her own passions, dreams, and identity. Each woman was already living an

incredible life that her children would one day follow. Their identities as young Black girls in Georgia, Grenada, and

Maryland influenced the ways in which they would approach motherhood. Their exposure to racist and sexist violence

from the moment they were born would inform the lessons they taught their children. Their intellect and creativity led

to fostering such qualities in their homes. The relationships they witnessed in their parents and grandparents would

inspire their own approaches to marriage and child-rearing. Highlighting their roles as mothers does not erase their

identities as independent women. Instead, these identities informed their ability to raise independent children who

would go on to inspire the world for years to come.

These women’s lives create a rich portrait of the nuances of Black motherhood. Yes, all three were mothers of sons who

became internationally known, and their stories share many similarities, but by no means can their identities be

reduced into one. Each woman carried different values, faiths, talents, and traumas. I hope their rich differences

will open our eyes to the many influences and manifestations of Black motherhood in the United States and beyond.

The narratives of these three women have fueled and empowered me, but this work has been extremely difficult at times.

Black motherhood in the United States is inextricable from a history of violence against Black people. American

gynecology was built by torturing Black women and experimenting on their bodies to test procedures. J. Marion Sims,

known as the father of American gynecology, developed his techniques by slicing open the vaginal tissues of enslaved

women as they were held down by force. He refused to provide them with anesthesia. François Marie Prevost, who is

credited with introducing C-sections in the United States, perfected his procedure by cutting into the abdomens of

laboring women who were slaves. These women were treated like animals and their pain was ignored.

There is a paradoxical relationship between the dehumanization we Black women and our children face and our ability to

resist it. Beyond the normal worries all mothers encounter as they progress through pregnancy and get closer to their

labors, we Black mothers are aware that we are risking our lives. Black women in the United States are more likely to

die while pregnant and while giving birth than other mothers. Beyond the normal fear that all mothers feel when the

gut-wrenching thought of losing their child creeps its way into their minds, we Black mothers experience a heightened

level of worry. We are aware of how differently our children are seen and treated in society, and our fears are

confirmed by articles and news stories reporting the violence that Black children experience constantly, whether at

parties, in school, or at their local parks. This fear continues as our children become adults who are in danger even

as they sleep in their beds, sit in their own apartments, when they call for help, or when they go on a run.

Louise, Berdis, and Alberta were well aware of the dangers they and their children would be met with as Black people

in the United States, and they all strove to equip their children not only to face the world but to change it. With

the knowledge that they themselves were seen as “less than” and their children would be, too, the three mothers

collected tools to thrive with the hopes of teaching their children how to do the same. They found ways to give life

and to humanize themselves, their children, and, in turn, our entire community. As history tells us, all of their sons

did indeed make a difference in this world, but they did so at a cost. In all three cases, the mothers’ worst fears

became reality: each woman was alive to bury her son. It is an absolute injustice that far too many Black mothers

today can say the same thing.

In the face of such tragedy, each mother persisted in her journey to leave this world a better place than when she

entered it. Yet their lives continued largely to be ignored. When Malcolm X was assassinated, when Martin Luther King,

Jr., was killed shortly after, and even when James Baldwin died from stomach cancer years later, their works were

rightly celebrated, but virtually no one stopped to wonder about the grief their mothers were facing. Even more

painful to me is the fact that their fathers were mentioned, while their mothers were largely erased.

I chose to focus on mothers of sons. Black men were certainly not the only leaders of the civil rights movement;

mothers of revolutionary daughters have also been forgotten. I simply chose three figures who are often put in

conversation together and who demonstrate the distressingly strong erasure of identity in the mother/son relationship.

Coincidentally, I gave birth to a boy, my incredible little boy, and I have already faced others’ attempts to erase my

influence on his identity. Phrases like “He’s strong, just like his father!” or “He’s already following in his dad’s

footsteps” when he reaches a milestone cause more harm than people think. By choosing three mothers of sons, I do not

want to erase daughters or other children. I am instead making the point that no matter our gender, everything starts

with our birthing parent.

In telling the stories of these three mothers, I hope to join others who have responded to Brave’s call for “Black

women to carry out autonomously defined investigations of self in a society which through racial, sexual, and class

oppression systematically denies our existence….” It is crucial to understand the layers of oppression Black

women face, while remembering that solely studying oppression keeps us from honoring “the ways in which we have

created and maintained our own intellectual traditions as Black women.” I pay close attention to this balance and bear

witness to the many challenges Berdis, Alberta, and Louise faced while acknowledging their ability to survive, thrive,

and build in spite of them.

Louise, Berdis, and Alberta were all born within six years of each other, and their famous sons were all born within

five years of each other, which presents beautiful intersections in their lives. Because they were all born around the

same time and gave birth to their famous sons around the same time, and two of them passed away around the same time,

I reflect on Black womanhood in the early 1900s, Black motherhood in the 1920s, and their influence on the civil

rights movement of the 1960s. The first of the three mothers was born in the late 1890s, and the last of the three

passed in the late 1990s. Their lives give us three incredible perspectives on an entire century of American history.

By seeing the United States develop through the lives of Berdis, Alberta, and Louise, you will be left with a richer

understanding of each world war, the Great Depression, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance, race riots, police

brutality, welfare debates, the effects of policies proposed by each president they lived to witness, and much more.

But their stories go beyond a new understanding of American history, especially the civil rights movement of the

1960s. An ode to these three women is an ode to Black womanhood—perhaps Black women of today will also be able to find

themselves in the life stories of Berdis, Alberta, and/or Louise, as I have.

Excerpted from The Three Mothers. Copyright © 2021 by Anna Malaika Tubbs. Excerpted by Permission of Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan Publishers. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

We hope you enjoy the book recommended here. Our goal is to suggest only things we love and think you might, as

well. We also like transparency, so, full disclosure: We may collect a share of sales or other compensation if you

purchase through the external links on this page.

[ad_2]

Source link