[ad_1]

In 1940s Orange County, future California Supreme Court justice Cruz Reynoso was just a teen trying to fight racism when he wrote to the U.S. postmaster general.

His family lived in a rural part of La Habra, where the Ku Klux Klan had held the majority of City Council seats just a decade earlier and Mexicans were forced to live on the wrong side of the tracks. Reynoso’s parents and neighbors had to travel a mile to the post office for their mail because the local postmaster claimed it was too inconvenient to deliver letters to their neighborhood.

Reynoso didn’t question this at first — “I just accepted that as part of the scheme of things,” he’d tell an oral historian decades later, in 2002.

But one day, a white family moved near the Reynosos and immediately began to receive mail. The teenage Cruz asked the postmaster why they were able to receive mail, but his Mexican family couldn’t. If you have a problem with this, the postmaster replied, write to her boss in Washington D.C.

So Reynoso did.

He gathered dozens of signatures for a petition and sent it off to the U.S. postmaster general asking for a change. A couple of months later, Reynoso received a response: His neighborhood would begin to receive mail.

“To me, it was sort of a confirmation of what I was reading in our textbooks, that we are a democracy,” Reynoso proudly recounted to the oral historian.

La Habra’s postmaster wasn’t as happy. When Reynoso went to thank her for what he assumed was her help in the matter, she blew him off.

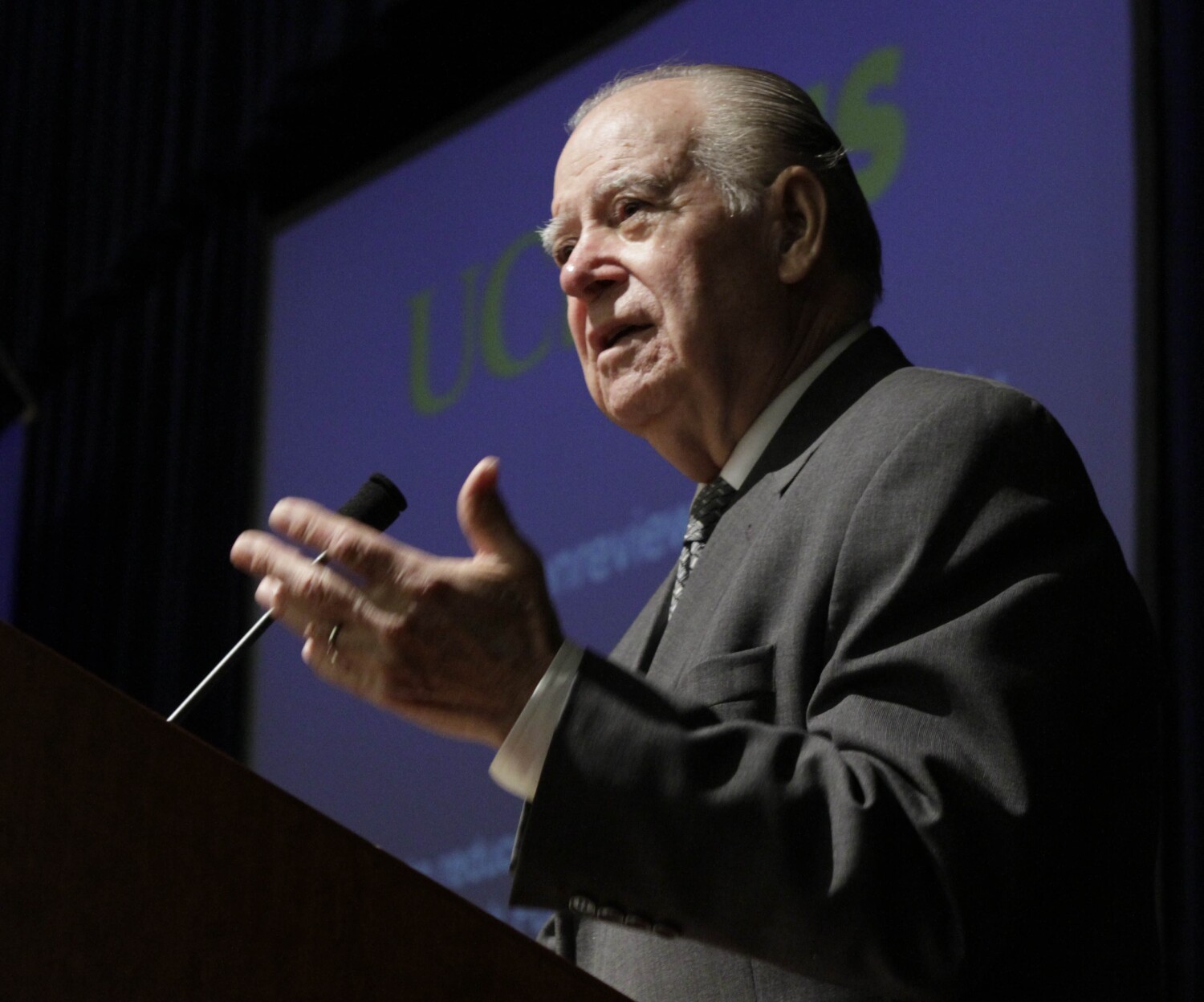

It set a precedent for how Reynoso, who passed away yesterday at 90, lived his professional life. At every step, the powers-that-be tried to cancel this son of Mexican immigrants.

Then-California Gov. Ronald Reagan repeatedly vetoed federal funds for the California Rural Legal Assistance while Reynoso headed the office and even signed off on an investigation that accused the nonprofit of trying to foment murders and prison riots (the investigation went nowhere). Former appellate Justice George E. Paras labeled Reynoso “a professional Mexican rather than a lawyer” and his 1982 nomination for a seat on the California Supreme Court a “disgrace” because Reynoso dared hear out Latinos and minorities in a system that for too long just rubber-stamped decisions against them.

Gov. George Deukmejian took the baton from Paras and heartily supported the movement that ultimately unseated Reynoso in 1986 along with Chief Justice Rose Bird and and fellow justice Joseph Grodin for allegedly being too liberal. And President George W. Bush replaced Reynoso on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights just a week after the group released a report that claimed Dubya’s civil rights policies “further divide an already deeply torn nation.”

Even in death, Reynoso’s opponents are trying to beat him. Most Californians, if they’ve ever heard of him, just remember Reynoso’s historic defeat, the only time voters ever rejected sitting California Supreme Court justices. It’s a narrative long tossed around by California’s political class. But his legacy will outlive the haters by decades.

He came out the better every time someone tried to knock him down. He continued his battles to open doors for those who followed in his wake, and inspired Latinos on the sidelines. During his lifetime, the powers-that-be in California turned from conservatives and liberals alike who favored the gentry to true-blue progressives devoted to uplifting the same underserved communities for whom Reynoso alway advocated.

Reynoso quietly became one of the most influential-yet-unknown Latinos this state has produced. That’s why the outpouring of universal respect in the wake of his death is unlike any I think we’ll ever see with another state Latino leader.

“He was always my example of holding strong to your values,” tweeted Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D–San Diego), a former Reynoso student when she attended UC Davis, adding that he was a “hero.”

“Those who knew him recall how this towering figure of Latino civil rights was unfailingly humble and gracious, even towards his opponents,” wrote the United Farm Workers in a press release.

Monterey County Supervisor Luis Alejo, another UC Davis pupil of Reynoso, remembered how his generation saw Reynoso as “mythical.”

“At a different time than today, he was taking on people like Reagan and Deukmejian and was still able to come out on top and be seen as a model,” said Alejo, who became a Reynoso family friend. “And he never asked for the limelight, or awards or anything. He just always felt his work was unfinished.”

The fights for Reynoso started when he was young. In elementary school, his classmates called him “profe” — the Mexican Spanish nickname for a professor — as an insult. As a high schooler, he helped desegregate school dances for junior high students in La Habra. As a young man, Reynoso became an assistant Scoutmaster to help start a Boy Scouts troop in his hometown — probably the first in Orange County comprised mostly of Latinos.

“[Latinos] sort of understood, generally, that it was our role in society to be the workers and not to be the professionals, not to be the folk who ran things,” Reynoso said of those days. “I never accepted that”

One summer, he and his family went to pick grapes in the Central Valley. During a break, Reynoso asked the field foreman how long the season would last because he wanted to return to school. The foreman laughed and told him Reynoso was the first Mexican he ever knew who valued education.

“It made me so mad,” Reynoso told an oral historian, “that I told myself that someday I’d go look him up, and I’d have my college degree in my left hand, and I’d hook him in the nose with my right hand.”

He never did — he didn’t have to. Reynoso instead channeled his anger into becoming a lawyer, a profession he chose in high school because “I had an urge to do something about the injustices that I saw around me.”

In many ways, his biggest loss — the 1986 electoral loss — became his biggest victory. That allowed him to travel the state and tell his story to basically any group that invited him right up until a couple of years ago.

“Cruz would never say no, and never asked for an honorarium — not even for gas,” Alejo said. “Even in his later years, when he could’ve easily slowed down, he’d go wherever he could to inspire. He always took that seriously.”

That’s how I was able to see Reynoso once. In 2009, he was the keynote speaker at a banquet for the Orange County chapter of the League of United Latin American Citizens. I barely knew anything about him other than his judicial defeat.

His speech was so understated that I really can’t quote anything from it. But I do remember how long people stayed afterward to shake hands with him, like few other speakers I’ve ever seen. Everyone wanted their moment for the barrio boy who won.

[ad_2]

Source link