[ad_1]

By: Neeta Lal

Bindiya Kumari, 26, a farmer from Dumaria village, located 175 km from capital city Patna in India’s poorest state of Bihar, has had two miscarriages since her marriage in 2018. Her plight sadly is neither rare nor exceptional. She and millions like her are the victims of a grossly substandard health care system that seriously neglects women and whose defects have been tragically magnified by the second wave of the coronavirus that has been ripping through the country.

The nearest hospital in Dumaria is 20 km away, Kumari says, so each time her delivery date arrived, the arduous journey to a medical facility in a rickety bus caused excessive bleeding, resulting in the death of her two unborn children.

“My mother-in-law is always taunting me that despite three years of my marriage to her son, I’ve not been able to give her a grandchild,” Kumari said. “But is it my fault that we don’t have a good hospital in our village? None of the politicians who come rushing in at election time have bothered to focus on our health problems.”

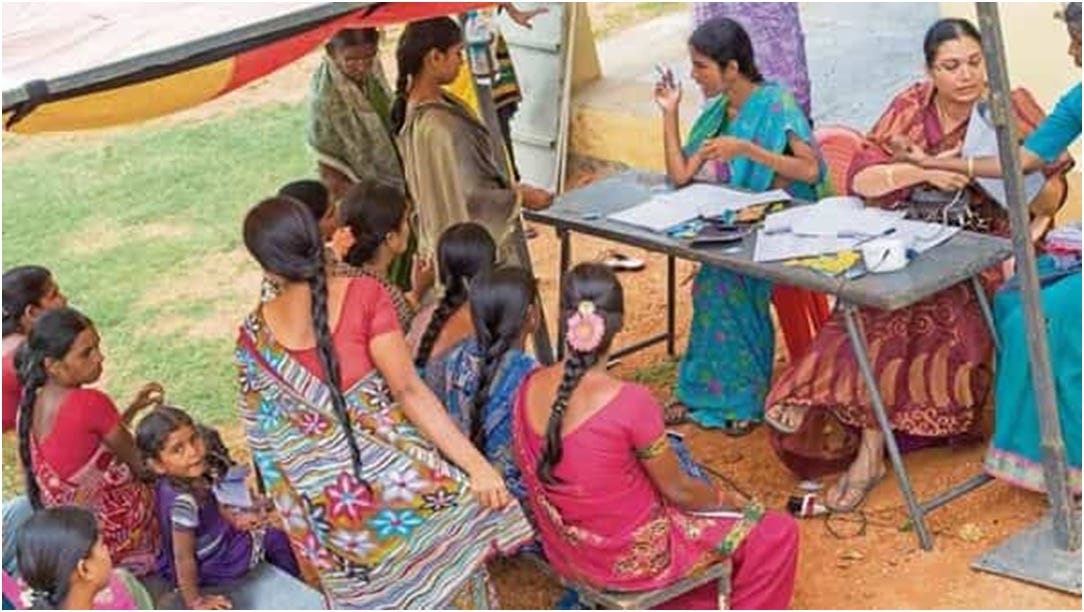

Thousands of Indian villages are bearing the brunt of a rudimentary health care system characterized by lack of funds, skeletal medical staff, paucity of critical lifesaving equipment and bureaucratic apathy. In what many have termed as India’s “Covid Apocalypse,” millions of hapless patients and their families are scrambling to secure the most basic life-saving drugs and services. So far the virus has afflicted more than 22.6 million people, the second-worst total in the world after the United States, and killed more than 246,000 people.

The ramifications of the unprecedented crisis will be especially grim for women’s health, studies say. A recent Unicef report, Direct and Indirect Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic and Response in South Asia, estimates that pandemic-related disruptions will result in a dramatic spike in maternal and child deaths, unwanted pregnancies and disease-related mortality in women and adolescents. India is expected to record 154,000 child deaths while maternal deaths are expected to surge by 18 percent, stillbirths by 10 percent. Of the 3.5 million additional unintended pregnancies estimated due to lack of access to reproductive healthcare, three million are likely to be in India, according to Unicef.

Further research by the Foundation for Reproductive Health Services underlines how 26 million couples in India won’t have access to contraceptives due to the pandemic, resulting in an additional 2.4 million unintended pregnancies. Nearly two million people will be unable to access abortion services.

Clearly, the Indian government has learned nothing from the pandemic’s first wave, experts say, even though evidence from past epidemics, like Ebola and Zika, has demonstrated that in times of crisis, women’s health takes a back seat in governments’ priorities. That is because funds and health resources are diverted to other avenues, heightening the risk of unintended pregnancies, maternal health risks, and unsafe abortions.

Restrictions on mobility during the current pandemic have only made things worse.

“Lockdowns and fear of catching the dreaded coronavirus at hospitals are inhibiting families from visiting hospitals for maternal checkups, driving up pregnancy-related complications,” said Savitri Devi, an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) employed under the government’s National Rural Health Mission. Devi is posted to a district hospital in NOIDA district in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh.

The pan-India nonprofit Population Foundation of India, which promotes and advocates gender-sensitive population policies and strategies, notes that women’s access to contraception, post-natal care services and institutional deliveries have plunged significantly in the pandemic year.

According to Poonam Muttreja, executive director of the foundation, India’s fragile healthcare sector is not equipped for the unprecedented rise in Covid-19 cases in this second wave. With only five hospital beds per 10,000 population and 8.6 physicians for every 10,000 people, the country lacks the requisite infrastructure for a crisis of this magnitude, she said.

The foundation’s own analysis of the first lockdown shows that women’s access to contraception, ante-natal care services and institutional deliveries have all been compromised as hospitals struggle to attend to critical patients. In backward states like Bihar, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, adolescents reported an unmet need for reproductive health services, especially menstrual hygiene products.

Experts point out that the mess is a direct result of India’s undercapitalized health care system, a result of one of the world’s lowest spends on health. India spends only 1.3 percent of its GDP on health as compared to the OECD countries’ average of 7.6 percent and other BRICS countries’ average of 3.6 percent. India’s military spend, however, is 2.9 percent of GDP (China’s is lower at 1.7 percent).

By contrast, in its latest report, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute revealed that India is the third highest spender on acquiring arms and its military expenditure grew by 2.1 percent since last year as against China’s more moderate 1.9 percent, a fact that has evoked sharp criticism at home.

Dr. Pratibha Khandelwal, Obstetrician and Gynecologist at Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, notes that another acute problem – inequitable distribution of health resources – bedevils much of rural India.

“Despite the authorities launching an array of targeted sexual and reproductive health interventions, our field studies reveal that they benefit 95 percent of economically empowered women as against 59 percent of the underprivileged,” she said.

Even the government’s flagship Beti Bachao Beti Padhao program, which focuses on women’s health and education, has facilitated only marginal improvements in enhancing the sex ratio at birth from 918 in 2014-15 to 934 in 2019-20, Khandelwal added. “Despite national campaigns emphasizing women’s free choice in opting for contraceptive methods, state governments continue to push female sterilization leading to coercion and risky substandard sterilization procedures, reflecting a patriarchal mindset.”

According to Unicef estimates, India would have the highest number of forecast births, at 20 million, in the nine-month period dating from when Covid-19 was first declared a pandemic. Also, of around seven million unwanted pregnancies globally, a little over two million will be in India alone. CARE International, in first-of-its-kind research across 40 countries, found that 27 percent of Indian women reported an increase in mental illnesses – compared to only 10 percent of men.

This skewed pattern paints a picture of missing political will, say health activists. When the will is present, they point out, much can be achieved, such as the improvement in India’s Maternal Mortality Rate, which plummeted from 122 in 2015-17 to 113 in 2016-18 through public sensitization campaigns. The rate of institutional deliveries surged from 18 percent in 2005 to 79 percent in 2016.

A gender-sensitive health framework with urgent attention from all stakeholders is the need of the hour, Khandelwal said. “The pandemic has been a wakeup call for the government to invest in public healthcare and prioritize the health of women, who make up almost half of India’s 1.3 billion population. It’ll be a shame if they don’t learn even now,” she concludes.

[ad_2]

Source link