[ad_1]

SRINAGAR, INDIAN-ADMINISTERED KASHMIR – When the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) were firing missiles at Gaza on May 14, thousands of miles away, in Indian-administered Kashmir’s Srinagar, 32-year-old artist Mudasir Gul stepped out of his home with his painting supplies. He climbed the pillars of a bridge and painted the face of a woman, her head wrapped in the Palestinian flag, and tears rolling from her eyes. Next to this poignant expression of what was happening in Palestine, Gul wrote, “We are Palestine” in an expression of solidarity, something Kashmir has always offered to Palestine.

Within a few hours, he was in jail.

Kashmir has a history of erupting in protests whenever Israel attacks Palestine. The recent attacks in Gaza and on the Al-Aqsa mosque and the killing of hundreds of people, including children, in IDF airstrikes, have drawn severe condemnation in the Kashmir region. But unlike in the past, except for a few examples of sloganeering over the past week, Kashmiris have not come out on the roads this time to protest against the attack on Palestine. The restive Himalayan region has not seen many street protests since August 5, 2019, the day the Indian government stripped the disputed territory of its quasi-autonomous status and tightened its control through bureaucracy, police, and army.

The latest case in point is the arrest of two sons of the deceased Kashmiri pro-freedom leader Mohammad Ashraf Sehrai. Soon after the burial of Sehrai, police booked 20 people for raising pro-freedom slogans. Later, two of Sehrai’s sons were arrested and booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), a stringent anti-terror law.

The Jammu and Kashmir Police have for the last three years arbitrarily invoked UAPA, India’s foremost anti-terror law, against dozens of civilians, journalists, and political activists. The law allows the government to jail for six months, without a trial or bail, anyone they might deem capable of committing a crime in the future. With such laws in place, the fear of reprisals pushes people into self-censorship.

But when Israel bombarded Gaza with airstrikes, protests broke out in a Srinagar locality on May 14. Like almost everyone in Kashmir, Mudasir Gul said, he could not “tolerate the bloodshed in Palestine.” So he did what he thought could express his anguish and feelings: He painted graffiti.

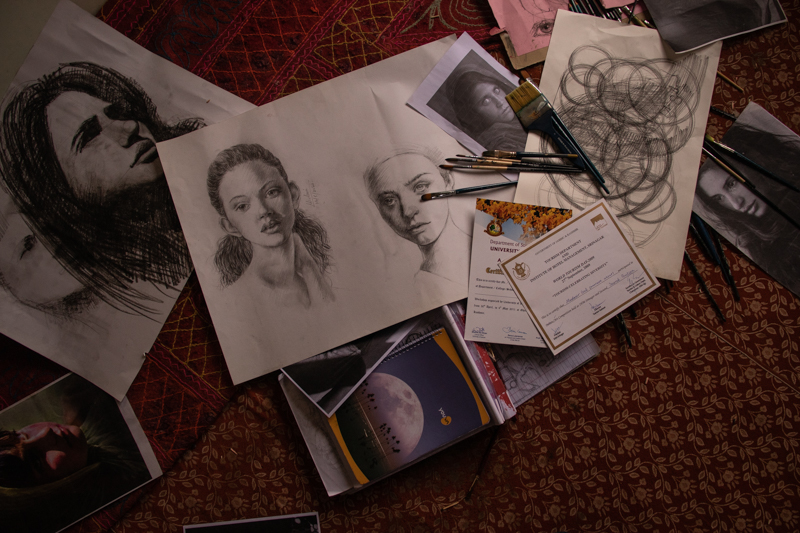

Mudasir Gul in his room in Srinagar, where he spends time sketching and painting realistic subjects. Photo by Zainab.

“The idea of graffiti struck me when I watched the bloodshed in Palestine. As a Muslim, I could not tolerate what was happening in Palestine,” Gul told The Diplomat.

Besides, Gul thought making graffiti would be safe. He said his graffiti was not anti-national – the current government levies the charge of being seditious against most dissenters. “I thought this graffiti was not related to India, so it would be safe to do. But when I was arrested, I realized even such artworks and graffiti have no place in Kashmir,” Gul said.

Given how the police have tightened their control, such graffiti was bound to land the artist in trouble.

During past civilian uprisings in Kashmir, several underground and anonymous artists would paint the walls with anti-India and pro-freedom graffiti. Several walls and buildings still carry such writings, while the rest of them have been defaced.

Gul’s attempt at graffiti was one of the latest examples, but it came in a whole new political setup. Soon after the situation escalated in Palestine, the Jammu and Kashmir Police issued a stern statement. On Twitter, the force said they were “keeping a very close watch on elements who are attempting to leverage the unfortunate situation in Palestine to disturb public peace and order in the Kashmir valley.”

Gul said after he finished painting the graffiti, he saw the protesters were being chased away by the police. “I also started running.” But within five minutes, he said, he got a call from the police, asking him if he had painted the graffiti. “I confessed I had made it. They asked me to deface it and I followed [the order],” the artist said, adding he did not want the police to raid his home at night and harass his family.

The defaced pro-Palestine graffiti painted by artist Mudasir Gul in Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir. Photo by Zainab.

Gul was later detained for three days. “It was a small room, stinking of urine, and there were eight of us huddled in that small space,” he said. The artist was released after a huge public outcry.

Mudasir Gul was not the only one to land in jail. The Jammu and Kashmir Police has arrested at least 20 people across the valley over protests in support of Palestine. The police said they wouldn’t allow “cynical encashment of the public anger to trigger violence, lawlessness and disorder on Kashmir streets.”

On Eid-ul-Fitr, the holiday marking the end of Ramadan, prominent Muslim religious preacher Sarjan Barkati was praying for the Palestinian people when he raised slogans in solidarity with Palestine at a mosque in south Kashmir.

Two days later, police arrested Barkati from his residence. However, the police said he was arrested for violating COVID-19 standard operating procedures and related advisories.

The police added that “all irresponsible social media comments that result in actual violence and breaking of law including Covid protocol will attract legal action.”

It’s not the first time Kashmiris have been arrested over protests against IDF strikes in Palestine. The situation has turned violent in the past: In July 2014, one protester was killed and several injured in south Kashmir when the police opened fire.

However, the police have been clear about the redline this time. In a statement, they said, “Expressing an opinion is freedom but engineering and inciting violence on streets is unlawful… We are a professional force and are sensitive to public anguish. But J&K Police has a legal responsibility to ensure law and order as well.”

Police surveillance on social media commentary related to the Palestinian situation has forced several users into self-censorship. Several Twitter and Facebook users in Kashmir whom The Diplomat spoke to said they had either toned down the language of their posts related to Palestine or completely abstained from posting anything.

Gul’s case also reveals self-censorship following the police action. When asked if he would attempt graffiti again in near future, Gul was quick to comment: “Unfortunately, I have to say that after what I witnessed and went through, it is clear that freedom of expression is absent in Kashmir. For now, I will focus on my landscape and portrait artworks.”

Gul’s idea behind painting the graffiti was that the street protest would have wound down quickly, but “the artwork is there to stay and it had a value,” the artist, who earns his living by painting murals and occasionally teaching at private schools, said. “But when I was arrested, I realized graffiti has no place in Kashmir.”

Some of the artworks by Mudasir Gul strewn in his room in Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir. Photo by Zainab.

Kashmiri politician and Jammu and Kashmir National Conference leader Imran Nabi Dar told The Diplomat that the police “overreacted to this whole episode.”

“As far as I am aware, they (protesters) were just expressing their displeasure and it was a peaceful non-violent demonstration. There was no need to arrest these youngsters; they were showing their solidarity with innocent victims of Palestine,” Dar said.

He said the administration in Kashmir needs to act according to the Indian government’s official position on Palestine: that India supports the Palestinian cause and endorses the two-state solution.

The Kashmir-based political analyst and noted academician Sheikh Showkat Hussain told The Diplomat that “restrictions, whenever and wherever imposed, to curb freedom of expression on emotional issues cultivate simmering dissent.”

“It erupts at any time like a volcano, taking everyone, including those who try to suppress it, by surprise,” Hussain said.

He added that police are scared that Kashmiris may imbibe the Palestinian traits of resistance, which might “puncture their claim of (enforced) normalcy that they are trying to market desperately.”

Gul sums up the curbs on freedom of expression in Kashmir with a quip: “There is a saying that an artist has no boundaries. But in Kashmir, we live in those boundaries.”

[ad_2]

Source link