[ad_1]

By: Murray Hunter

Malaysia’s shaky, deeply unpopular government is seeking to regain control of the narrative in the internet age via dramatic use of police power to harass and investigate activists, journalists, and social media users. Foreign news reports from investigative journalism websites Asia Sentinel and Sarawak Report have been blocked periodically by the Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission.

Local media rarely issue critical reports out of fear of prosecution. Blogs, like Mariam Mokhtar’s Rebuilding Malaysia, are suffering periodically distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, in which targeted websites are flooded with tens of thousands of responses, overloading the websites and crashing them.

That has led to a fall in Malaysia’s position on the World Press Freedom Index by 18 positions to 119th of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders 2021 annual report, the largest fall by any country in the history of the index, and in stark contrast to a rise by 22 places in the last annual report, which coincided with the arrival of the ousted Pakatan Harapan government in power.

In addition, the Freedom House annual country report has now classified Malaysia as only partly free on its index measuring civil rights, freedom of expression, and civil liberties. Human Rights Watch’s annual report on Malaysia described the country as existing within “a culture of fear, where peaceful expression is criminalized.”

The government has historically played up the need to avoid discussion on so-called “sensitive issues” including race, religion, the royalty, education, and citizenship, on the pretense that such issues will inflame community relations. Prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin, the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Shah, and the former police commissioner Abdul Hamid Bador, have all warned the public not to raise these “sensitive issues” in order to maintain peace and harmony within the country.

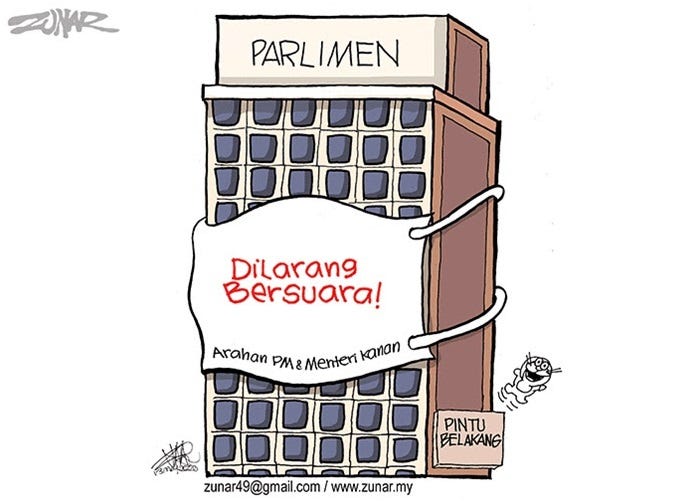

A network of laws designed to restrict freedom of speech has been put in place. The draconian Sedition Act, which the former Pakatan Harapan government vainly promised to repeal, is being used to prosecute satirists. In 2015, the act was widened to include social media comments. Graphic artist Fahmi Reza Mohd Zain was arrested over his ‘Dengki Ku’ Spotify playlist, posting a jealousy theme, over comments made by the queen in regards to vaccinations. Cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque, known popularly as Zunar, was summoned by police for his satirical cartoon over the Kedah Chief Minister canceling the Hindu Thaipusam holiday, in the Malaysiakini news website.

Speaking out forbidden on instructions from prime minister

Journalists are often summoned for questioning for long periods, as recently happened to two Malaysiakini journalists, Rusnizam Mahat and Aedi Asri Abdullah, over their reporting of police brutality in the detention and subsequent death of a prisoner. This was after several Al Jazeera journalists were summoned to police headquarters last year for investigation of sedition and defamation over the documentary about Malaysia’s treatment of undocumented workers was aired on television.

Police investigations also use the framework that the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) which forbids any improper use of computer and network facilities, and bans the dissemination of statements, rumors, or reports that may cause public mischief. This act is also used to block news websites that are critical of the government, report corruption, or have comments posted by readers which authorities deem offensive.

The popular news portal Malaysiakini is currently appealing a conviction and RM500,000 fine for contempt of court over comments made by five readers on their platform which were almost immediately erased after authorities brought them to editors’ attention. Several people have been prosecuted under this act for insulting the Malay rulers on social media. This act appears to be used as a de facto lèse-majesté law over the past 12 months.

Although the Anti-Fake News Act 2018 was repealed in 2019, the penal code and Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA), offers many provisions to prosecute. Former Pakatan Harapan deputy minister Fuziah Salleh has been charged with putting up “fake news” on her Facebook account last year, under the penal code and CMA. Fuziah has claimed trial over the charge.

The penal code carries several sections for criminal defamation. Although media outlets benefit from some protection, if they can prove facts reported are correct, and published without malice, bloggers are not afforded this protection. Statements intended to cause “fear and alarm to the public”, or “commit an offense against the state or public tranquility” are criminally punishable. A journalist Wan Noor Hayati who criticized the government on Facebook for allowing a Chinese cruise ship to dock in Malaysia during the Covid-19 pandemic, was charged under the penal code.

Proclamation of an emergency by the King, widely perceived as a subterfuge to keep the current government in power, has re-criminalized the circulation of what the government perceives as fake news. Thus it has the power to impose its own version of the truth.

The Printing Press and Publishers Act (PPA) is being used to limit the circulation of newspapers, and suspend their publication. A recent book, “Rebirth: Reformasi, Resistance and Hope in New Malaysia,” published by GerakBudaya in Kuala Lumpur was banned last year. Police raided the publisher’s offices, seizing copies of the book. Even though most of the chapters had previously been published as articles in 2018 without issue, and the cover was a painting produced back in 2014, deputy director of Criminal Investigation Mior Faridalathrash Wahid claimed some articles within the book were considered seditious.

Politicians, police and other authorities regularly use intimidation and threats to sue journalists under civil defamation laws to silence critics. A retiree, Abdullah Sani Ahmad was fined RM2,00 last year, for criticizing the health minister. Last year, the director-general of immigration Khairul Dzaimee warned that foreigners living within Malaysia who criticize the government will have their visas revoked and be deported. When the Asia Sentinel exposed corruption within JAKIM over Halal certification, then deputy minister for religious affairs Fuziah Salleh attacked the credibility of the online news portal, rather than investigate the allegations.

The police and the communications ministry actively monitor both media and social media, particularly for insults against Islam and royalty. This was confirmed by former Pakatan Harapan minister for Religious affairs Mujahid Yusof Rawa, who publicly announced that a special unit has been established to monitor social media content to find insults to Islam. Authorities collaborate with mobile telecommunication companies to intercept and monitor online and mobile communications, such as “Whatsapp” groups.

Much of this is undertaken without warrants, using the Security Offenses (Special Measures) Act 2012. It has been documented that Malaysia is in possession of servers and software that are capable of stealing passwords, tapping internet calls, and intercepting messages. The government also purchased from Israel a system that can eavesdrop on telephones, monitor emails, and hack into apps.

The forced closure in 2016 of The Malaysian Edge after the online news portal reported on the 1MDB financial scandal has forced most online new portals to practice self-censorship. News reports and Op-Eds are scrutinized for comments on “sensitive” issues and are either not posted or edited. A longtime social activist and writer, Mariam Mokhtar, told Asia Sentinel that it has been getting very difficult to publish with online news portals. Educator and columnist Dr Azly Rahman, who has been commenting on the state of Malaysian political and educational affairs, had his position as a columnist with Malaysiakini terminated after editorial censorship and removal of one of his columns.

In today’s online media there are more Op-Eds and editorials by officials using pen names to push government lines. Online news portals are sometimes used by the government to attack critics without critics having the opportunity to reply.

In-depth investigative journalism is quickly disappearing. There are still some good original investigative articles coming out occasionally, New Straits Times, Cilisos, and Malaysiakini have shown that. Most journalists today lack brave peers and inspiring mentors. Journalists are treated as second class professionals, with politicians, royalty, the bureaucracy, and associations trying to cultivate and buy their loyalty. Favorable press often pays well.

Good investigative journalism is hindered by the Official Secrets Act, under which almost anything from a civil servant can be deemed a state secret and open to prosecution. Whistleblowers can be prosecuted for theft, charged under the OSA, or even harmed ex-judicially.

Freedom of speech is also suppressed institutionally. Academics at Malaysian public universities must obtain permission to appear on media, especially on social and political issues. Some commentators from public universities subtly follow the Ketuanan Melayu line in disguise. Television and radio stations are owned by those allied with government, and program managers are very selective about the guests they invite for appearances in interviews, panels and other discussion programs.

A Wikileaks release of a US cable, written in 2007, revealed that Malaysia’s premier think tanks, the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS), the Malaysia Institute for Economic Research (MIER), and the Asian Strategic and Leadership Institute (ASLI) are all funded, owned and influenced by the governing political parties, especially UMNO. They a major role in forming policy, drafting legislation, government committee staff appointments and influencing public opinion.

Through clandestine means, the government directly influences public opinion, with direct intervention into social media. Many sock puppet social media pages and identities exist. These accounts through Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, are run both by government and political parties. They act both as influencers and to attack those who peddle unwanted views. Some activities are outsourced overseas. Bot accounts are used to attack articles that criticize the government.

A number of political blogs are fronts for the government and governing parties to push particular narratives with the objective of defining what is politically correct. The range of sensitive issues is being dramatically widened to include social issues like LGBT, teenage pregnancy, sexual abuse, drug addiction and abortion. Dissent is being suppressed against both the monarchy and government. With a government that could fall within days of the cessation of the emergency, the situation is not likely to improve any time soon.

This article is among the stories we choose to make widely available. If you wish to get the full Asia Sentinel experience and access more exclusive content, please do subscribe to us.

[ad_2]

Source link