[ad_1]

As Indonesia pushes forward with its COVID-19 vaccine rollout, the nation faces substantial obstacles. Trying to administer vaccines to an archipelagic population of 260 million people spread over 6000 islands is no small task. But logistics and resources aside, Indonesia is facing a further hurdle: vaccine hesitancy.

In January 2021 polls suggested that 27 percent of Indonesians were hesitant to receive the vaccine; this hesitancy rate has risen to around 30-40 percent (https://saifulmujani.com/kepercayaan-publik-nasional-pada-vaksin-dan-vaksinasi-COVID-19/)

What is behind this vaccine hesitancy? To uncover the reasons, we conducted on-the-ground research in Sumatra, interviewing 50 women in the first few months of 2021 who had key vulnerabilities: 20 of these women were living with HIV; 20 were pregnant during the last 12 months; and 10 were front line health workers.

Our interviews revealed four key factors behind vaccine hesitancy: concern that the vaccine is not halal (permissible in Islam); fears over Sinovac as it comes from China (and has imagined links with Communist contagion); vaccine coercion; and belief in alternative ways of safely and effectively guarding against COVID-19 such as good hygiene practices.

The vaccine is not halal

I do not want to be vaccinated because the vaccine is from China, and there are pig parts in the ingredients. It is haram (forbidden) to put pig parts into my body. We will go to hell if we do it. (Yaya, a 50-year-old housewife) (all names are pseudonyms)

Indonesia has a relatively high acceptance rate of regular immunisation regimes. Indeed, around 80 to 90 percent of all babies under the age of one receive immunisations. Mothers we talked to noted that prior to COVID they would travel some distance and stand in long lines at public health centres to ensure their babies were fully immunised. This account suggests that Indonesia is a vaccine-accepting country. Furthermore, the current MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine is made in India and is widely suspected to contain pig products. Yet there has been no large-scale refusal of this vaccine in Indonesia, despite it not being certified halal.

But there is heated debate in Indonesia currently around the Sinovac vaccination, which is the main vaccine administered in Indonesia at the moment for COVID-19. Sinovac was developed by Chinese biopharmaceutical company Sinovac and is now made in partnership with Indonesian state-owned pharmaceutical firm PT Bio Farma. While AstraZeneca, Novavax and Pfizer have publicly stated that there are no pork products in their vaccines, Sinovac has refused to reveal whether its vaccine contains any pork products.

Given Indonesia is home to the largest population of Muslims in the world, not being able to confirm the halal status of the vaccine worries many. This worry persists despite Vice President Ma’ruf Amin, an influential Muslim leader, declaring that in emergencies such as a global pandemic, the vaccine does not need to be certified as halal to be permissible. But fear continues, and it continues despite other widely accepted vaccines (e.g. MMR) not being declared halal. We suggest, therefore, that it is not halal status on its own that is provoking vaccine hesitancy. Hesitancy is also due to the fact that there is suspicion of China.

Fear of Sinovac and China (and imagined links with Communism)

As far as I know, China bought vaccines from Europe, and Indonesia bought vaccines from China. Think about it! (Nay, 33-year-old working mother)

Part of the reason for vaccine hesitancy is that people are not convinced that the Sinovac vaccine is effective. As Nay suggests above, consumers are suspicious of why China would import a vaccine from Europe if their domestically produced one was effective.

But hesitancy also comes from a general distrust of China, including health products made by Chinese companies. This distrust extends from Indonesia’s long standing tension with Communism, which continues to be banned in Indonesia. Rumours thus circulate that China might be waging a proxy war against Indonesia by delivering a vaccine that might have fatal consequences.

Further, women told us they felt China was pushing a vaccine (of dubious efficacy and with potentially deleterious side effects) just to make money. This again taps into harmful stereotypes in Indonesia that Chinese businesses want to make a profit at any cost. Added to this profit discourse is the widespread belief that people from mainland China are coming to Indonesia to take away local jobs. There is thus a kind of grass-roots collective resistance against China and Chinese products, including vaccines, as Nika, a 29-year-old mother summarises:

The efficacy of the vaccines has not been proven with evidence. It could turn out to be medical malpractice. We hesitate then to take the vaccine and wonder if it is a vaccine or if it’s just vitamins. And where did the virus come from? And where is the vaccine made? Both in China! So maybe COVID-19 vaccines are just made for economic reasons to benefit China. China, you know, they are Communists. We have become experimental subjects, yes, guinea pigs (kelinci percobaan, literally test rabbits). For me, it is better to maintain our health, trust our body, and if we can maintain our health, then what is the COVID-19 vaccine for?

Vaccine hesitancy also stems from public distrust of the Indonesian government, which many people see as being too close with China. For instance, women noted that the government has not raised the issue of Sinovac needing to pass clinical trials and have its efficacy proven. Women mentioned that the Sinovac vaccine had not (according to their understanding) passed the Stage III Clinical Trial and they noted that the government had not transparently explained this. Women thus worried that the vaccine was not safe because it was only approved through an emergency permit granted by Indonesia’s Drug and Beverage Regulatory Agency. There is thus palpable suspicion of the vaccine in Indonesia and when this suspicion is met with a coercive vaccination program, you have a recipe for vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine coercion

From early January 2021, there was rampant social media messaging saying “I am ready to be vaccinated.” ] Such posts were shared by community health centres, hospitals and public health departments, healthcare organisations, and health workers themselves. There was hope that people would get vaccinated in good faith.

Figure 1: Social media message saying: “I am ready to be vaccinated” (Source: Ministry of Health Indonesia)

But shortly thereafter the government imposed the threat of fines of up to Rp 5 million (AUD$450) for people who refused the vaccine or who spread anti-vaccine messages (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-19/indonesia-warns-fines-for-refusing-COVID-19-vaccine-world-first/13170826). These fines were particularly aimed as health care workers and teachers, who were first in line for mandatory COVID-19 vaccines. Presidential Decree Number 14 of 2021, verse 13A, point 4, states:

Anyone designated as a core target for the vaccine, and who refuses the vaccine, will face an administrative sanction, including postponing or stopping social aid, postponing, or stopping administrative government services; and/or a fine (https://jdih.setkab.go.id/PUUdoc/176339/Salinan_Perpres_Nomor_14_Tahun_2021.pdf)

The coercive nature of the vaccine rollout has put many Indonesians offside, as Ati, a 30-year-old nutritionist, revealed: “We cannot reject the vaccination for COVID-19. Thirty of my friends refused the vaccine on health grounds and they were interviewed by staff from the Ministry of Health and the Public Health Office. After the interview, 28 were compelled to be vaccinated; only two had their wishes not to be vaccinated upheld.”

Related

Gendering Indonesia’s responses to COVID-19: Preliminary thoughts

The approach used in the creation of these policies ignores that women may face more difficulty in accessing the promised benefits.

The coercion to be vaccinated has concrete implications, as Hana, a 35-year-old woman who works in a public hospital noted: “From the bottom of my heart, I did not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. However, we would lose our job if we did not get the COVID-19 vaccination.”

Lala, a 30-year-old nurse, also mentioned that as a health worker she was obliged to get vaccinated and that her only choice was to agree to the vaccine or to lose her job. Lala also noted: “We are also afraid of accessing the COVID-19 vaccination. We are ordinary humans, we are afraid of taking the COVID-19 vaccine, but we need to take care of our own health.”

Part of the reason that people do not trust the Indonesian government in terms of the COVID-19 response, is that health messages have been unclear and caused confusion. One of the impacts of a lack of trust in the government is that women are now deciding not to bring their children in for regular immunisations, such as for measles. Yana, a 24-year-old mother said: “I decided not to immunise my second baby, who was born during this pandemic. I am afraid that the baby will not be given the regular immunisation, and I thought my child might be given the COVID-19 vaccine. For my older children who are school age, I will ask whether they will be vaccinated for COVID-19. If they tell me the children will be vaccinated for COVID-19, I will reject it for my children.”

Belief in harmful side-effects and alternative ways of guarding against COVID-19

Some women noted that they did not want the vaccine because they were worried about adverse side effects, which were heightened among women who had comorbidities. Kanya, an HIV-positive mother told us: “I do not want to get vaccinated as I do not want to take any risks. I have asthma and HIV. I am afraid of disclosing my HIV status.” Others mentioned feared an allergic reaction. Some of the women noted disbelief that COVID-19 is real, or at least belief that COVID-19 poses no real health risk. For instance, Diah, a 29-year-old small shop owner noted: “People surrounding me did not believe in COVID-19, how come they want to access COVID-19 vaccines” (see also http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue45/najmah2.html).

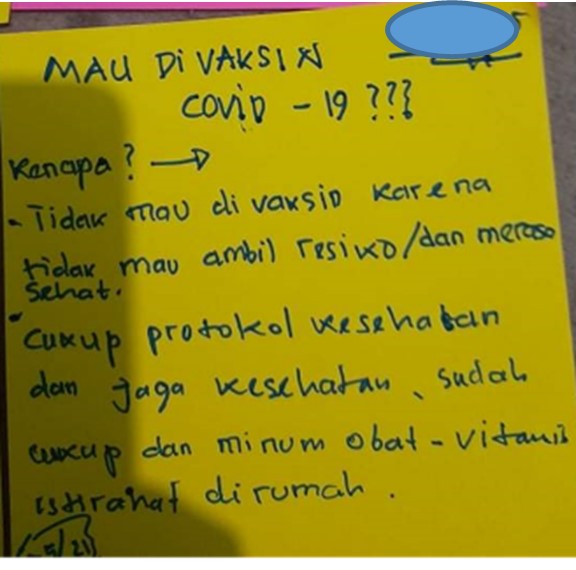

Worry and disbelief play into the promotion of alternative ways of guarding against COVID-19. Some women talked about alternative ways of protecting themselves. For instance, Anti, a 49-year-old housewife said: “I do not want to take any risk [by having the vaccine]. I feel healthy and I am in a good condition. I just need to perform the health protocols [e.g. hand-washing] and maintain my immunity by taking vitamins. I also need to maintain my health by eating nutritional food. If I feel sick and suffer from COVID-19 symptoms, I just need to take vitamins and have a rest at home, it is easier [than getting vaccinated].”

Figure 2: Mapping reasons women reject COVID-19. Source: Najmah (supplied by author)

Indonesia has a long way to go to gain public trust in its handling of COVID-19. There is little evidence that the government has implemented a national health solution, instead stoking public distrust through inconsistency and lack of transparency. To mitigate this doubt, the government should look to scientific evidence and effective communication, rather than coercive power and religious doctrine.

[ad_2]

Source link