[ad_1]

Well hello! I’m so glad you’re here. A version of this article also appeared in theIt’s Not Just You newsletter.Sign up here to receive a new edition every Sunday. As always, you can send comments to me at: Susanna@Time.com.

Well hello! I’m so glad you’re here. A version of this article also appeared in theIt’s Not Just You newsletter.Sign up here to receive a new edition every Sunday. As always, you can send comments to me at: Susanna@Time.com.

A slew of beloved friends have been having babies lately. I’m embarrassingly emotional about their arrival, or even just the news that they’re on their way. Knowing that this new crop of young ones will uncover delight in this bruised world is one of those ancient wonders.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

It’s been a fractious and scary year, but these pandemic babies will still laugh deliriously at the smallest of forgotten joys, like squeezing mashed potatoes through their fingers or grabbing the dog’s nose. And in turn, that’ll make the adults who love them lose themselves to joy. It’s an ordinary but precious intergenerational symphony: We believe our job is to teach kids everything, meanwhile, they’re reminding us how to live.

I like thinking that this newest generation will be an especially bright light, maybe because their existence is such a stubbornly optimistic bet on the future in the face of what economists predict will be a drop in birth rates for 2021. This delay in parenthood is the price of economic hardship, a pandemic, and political agonies across the globe.

Surely this baby bust will wane as we emerge into the light of what we hope will be a summer of optimism. However, the idea that so many people may have already put off having babies for financial reasons or because they’ve borne the brunt of the pandemic childcare nightmare is sobering.

Women, in particular, have spent the last 15 months stretching themselves to the breaking point to fill the massive gaps in our care economy during this long crisis, whether it’s working and homeschooling kids or taking care of elderly relatives, and often all three. No wonder some are holding off on having kids.

This saga reminds me of how my sister and I waited to have children like many in our cohort, and the story I wrote about that calculus of care–can your parents be the babysitters or will they need care themselves? It’s a question that’s even more relevant after COVID-19 and the toll it took on seniors.

THE GRANDPARENT DEFICIT

A few years ago I was sitting in the vast dining room of an assisted-living home in Washington, D.C., watching my then-5-year-old niece bounce like a pinball between tables of seniors. It was a startling sight–that small, bright-eyed blur amid a hundred crinkly faces. Her audience, mostly women in their 80s and 90s, grinned as she navigated all the parked walkers, canes, and wheelchairs as if it were a playground.

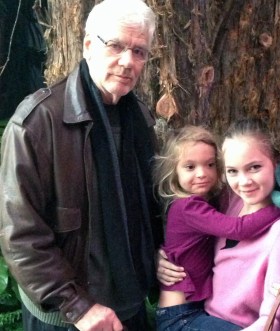

Sahar was a bit of a celebrity at the residence. Far younger than most of the other grandchildren who visit, she was a rare burst of kindergarten energy in a place where even the elevators move very slowly. She came frequently to have meals with my dad, her grandfather. He was 81, and she didn’t know what he was like before dementia took hold. Nor does she remember her grandmother who died several years ago, except in the funny stories my sister tells so often that Sahar refers to them as if they were her own memories.

These Gen Z kids have seen us juggle our jobs, their school schedules and their grandparents’ needs simultaneously–one day missing work to be at the bedside of a parent who’s had a bad fall, another day trying to call an elder-care aide from the back row of a dance recital.Sahar and my two children are among a growing number of kids who will see their grandparents primarily as people in need of care rather than as caretakers. They are the leading edge of a generation whose mothers and fathers had children later in life.

It seems naive to say this tripart balancing act came as a surprise to me and my sister, but it did. Somehow, while we were worrying about our biological clocks and our careers, it didn’t occur to us that another biological clock was ticking down: that of our parents’ health. And although medical science keeps coming up with new ways to prolong fertility, thwarting the frailties of old age is harder.

Our parents seemed so vibrant, so capable in their 60s that we couldn’t imagine how fast things would change. We knew that three or four years could make a huge difference in our fertility, but it turned out that three or four years could also mean the difference between a grandmother who can take a toddler to the beach and one who can’t lift her newest grandbaby out of a kiddie pool because of arthritis.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Subscribe here to get a weekly essay.

My children may face an even greater grandparent gap. I was almost 39 when I had my second child. If she has a child at the same age, I’ll be over 80 when that grandchild enters pre-K. And I’m not alone here: about six times as many children were born to women 35 and older in 2012 as they were 40 years ago.

I’m aiming to stay spry, but by the time I become a grandmother, I’ll likely be past the age that my daughter can drop her kids off at my house for a weekend. Will I be one of those exceptional octogenarians who jogs every day? Will I be able to babysit, or will I need my daughter to find me a babysitter? I don’t know. But with about half a million people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s each year, plus the usual maladies of age, there’s a fair chance I’ll need some kind of help.

If I had thought about all that, I might have gotten pregnant a few years earlier, just to give my kids that little bit of extra time with my parents in their prime. Of course, it’s not as if my sister and I could have chosen exactly when we met the men who became our children’s fathers.

Nor do I regret spending my 20s and part of my 30s living in different countries, doing all kinds of jobs, soaking up the world. It was glorious, and it made me a better mother. But I do know I’d give anything if my kids could have one more weekend at the beach with my parents in peak grandparenting mode–full of dumb puns and poetry and wry observations from the extraordinary lives they’d lived so fully.

And now, amid the ongoing debate over when to lean into a job or a relationship or children, my take has changed. I want to tell my kids, “Don’t forget the benefits of grandparents in the high-pressure calculus of modern life. I would like to make it easier for you if you want to lean in and have babies at the same time. I’d also like to know your children.” Who knows if I’ll get that chance, given the million variables at play, but I want them to know it’s an option.

With my father’s illness, my children discovered that they are not always the center of the world, and they learned to care for him which is a too-rare lesson.

And while my young niece (pictured between my dad and my youngest daughter above) never knew what my dad was like when he used to hide Easter eggs or swim after us pretending to be a shark, his white hair pluming like sea foam, she’s learning something beautiful from her mother. She saw my sister visiting him daily, feeding him, talking to him. Sahar saw kindness firsthand. And believe that she understood that the thin, confused man in the bed was someone worth loving. That he was family.

New to It’s Not Just You? Subscribe here to get a fresh edition of the newsletter every Sunday.

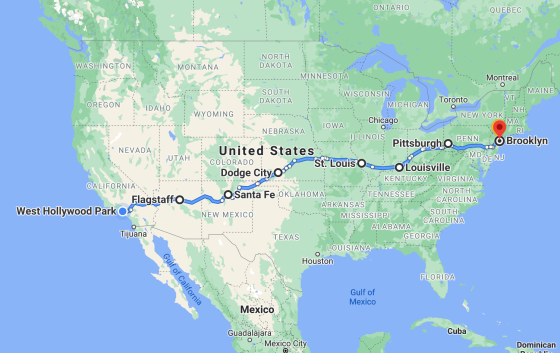

ROAD TRIP ALERT 🚗

Dog and I are departing for that long-awaited cross-country road trip with our friends on May 30th. I’ll be posting updates on Instagram @SusannaSchrobs. And if you have breakfast restaurant recommendations for any of these cities, DM me, or email me at Susanna@time.com with comments.

EVIDENCE OF HUMAN KINDNESS❤️

Here’s your weekly reminder that creating a community of generosity elevates us all.

A LOVE TRANSPLANT

Enam and Carlin Jordan, parents of three boys in North Carolina spend $2,000 to $3,000 per month on treatments for two-year-old ‘Baby Carlin’ who was born with sickle cell anemia, a blood disorder that disproportionately affects African Americans.

The Jordans, both of whom are youth pastors, are featured in an upcoming episode of Going From Broke, a streaming program that provides financial advice and strategies to those struggling with student loan debt. But because it was impossible for the family to manage their loans along with the burden of their son’s treatments, the show’s producers contacted Pandemic of Love, a grassroots mutual aid organization for help.

The only known cure for sickle cell disease is a blood stem cell or bone marrow transplant from a genetically matched donor. Carlin and Enam’s youngest son, six-month-old Caiden, is a match and could be a donor for his big brother, but the cost of this procedure is a staggering $40,000.

Enter Pandemic of Love. The group’s volunteers and donors were able to raise the funds needed to underwrite the cost of a bone marrow transplant which was not covered by the couple’s insurance.

Check out this emotional video clip in which Enam and Carlin were surprised with a check for their son’s transplant. The pair were moved to tears saying: “Words cannot describe how blessed our family has been by this generous and selfless donation.” (See the full episode about the Jordans in season two of Going From Broke.)

Story and images courtesy of Shelly Tygielski, founder of Pandemic of Love, a grassroots organization that matches volunteers, donors, and those in need.

COMFORT CREATURES

Our weekly acknowledgment of the animals that help us make it through the storm.

This is Spring, submitted by Melanie who writes: “This is my son’s first puppy and my first in over 17 years. She has brought so much love, joy, and chaos into our life.” (Send your comfort creature images with captions to: Susanna@time.com)

Share this edition of It’s Not Just You here.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? SUBSCRIBE to It’s Not Just You here.

[ad_2]

Source link