[ad_1]

China Power | Diplomacy | East Asia

Hungary under Viktor Orban has been the most China-friendly country in the EU in recent years. That might be about to change – drastically.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban talks to Chinese President Xi Jinping, not pictured, during a bilateral meeting of the Second Belt and Road Forum at the Great Hall of the People on Thursday, April 25, 2019 in Beijing, China.

Credit: Andrea Verdelli/Pool Photo via AP

Many observers were stunned to see pictures from Hungary of thousands of people marching in the streets, protesting the government plan to build an overseas campus of Fudan University in Budapest using taxpayer money. Only days before, Budapest Mayor Gergely Karacsony attracted international attention when he renamed the streets around the campus site with such names such as “Dalai Lama Street,” “Free Hong Kong Road,” “Uyghur Martyrs’ Road,” and “Bishop Xie Shiguang Road.”

Over the previous years, Hungary under Viktor Orban has become one of the most China-friendly EU countries, repeatedly preventing the EU from adopting critical remarks on China (which require consensus among the the bloc’s members). That might be about to change, however. For the first time in a decade, Orban is facing the possibility of losing to the opposition in parliamentary elections next year. And the opposition is finally expressing very different thoughts about China – thoughts that are actually more aligned with Hungarian public opinion.

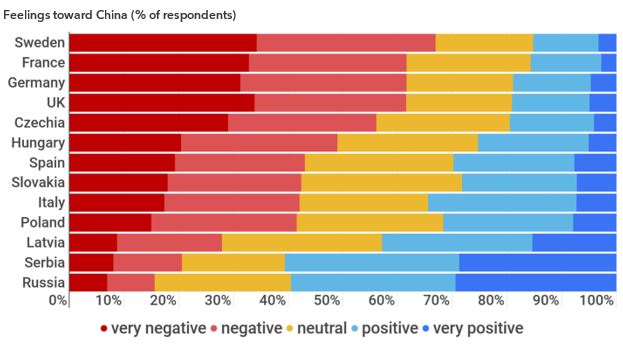

According to the Sinophone Borderlands survey from fall 2020, the Hungarian public has very different attitudes toward China compared to its government. Overall, almost 50 percent of Hungarian respondents held either negative or very negative views of China, while only about 25 percent held positive or very positive views. This means that Hungarians were more negative about China than, for instance, Poles, Slovaks, Italians, or Spaniards – and not much different from others such as Germans or the French. These findings certainly don’t make Hungary as much of an outlier as its official foreign policy might suggest.

Source: Sinophone Borderlands survey (2020).

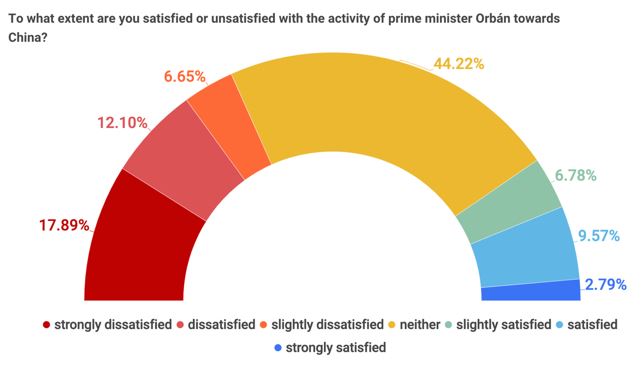

Indeed, there is little support among Hungarians for Orban’s policies toward China. Only about one-fifth of the respondents declared that they were satisfied with the activity of the prime minister toward China, while more than one-third was dissatisfied (the rest being neutral).

Source: Sinophone Borderlands survey (2020).

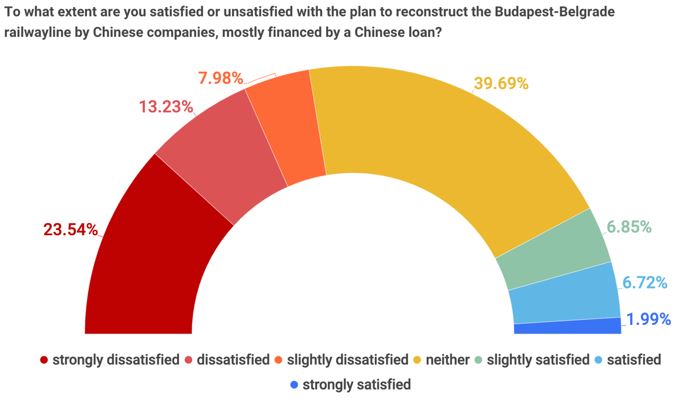

While we didn’t ask in the survey about the relatively recent Fudan University project, we did include a question on another project involving a similar amount of money, and meant to operate on the similar basis of a Chinese loan paid for by Hungarian taxpayers: the reconstruction of the Budapest-Belgrade railway. Here, the level of dissatisfaction is even higher: about 45 percent of respondents were dissatisfied, while only less than 15 percent were satisfied. Even more visible than in the previous question, a significant share of the respondents expressed “strong” dissatisfaction, while the share of those having neutral views was now smaller than those that were dissatisfied.

Source: Sinophone Borderlands survey (2020)

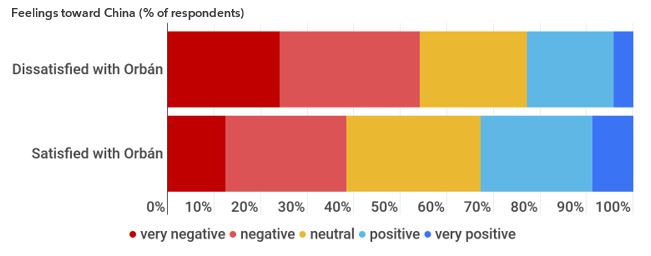

Zooming in on the political divisions, Hungarians who are satisfied with Orban are more positive about China than those who are dissatisfied with Orban. While the difference is large, it is worth noting that even the supporters of the prime minister are more negative than positive in their views toward China.

Source: Sinophone Borderlands survey (2020)

To sum up, more than 10 years of (sometimes very high-profile) China-friendly attitudes from Orban has led to some domestic divisions in terms of how his supporters and opponents perceive China. However, even Orban’s supporters seem to be predominantly negative about China and dissatisfied with his China policies. When combined with the sizable numbers of Orban’s opponents who are strongly dissatisfied, we begin to understand the reason for the recent public protests in Budapest.

China may become a political issue in Hungarian domestic politics and the opposition can appeal to the dissatisfied public by aligning more closely to the general sentiment on China than Orban has done.

[ad_2]

Source link