[ad_1]

In a classic example of civic action, conservatives have undertaken a variety of initiatives to counter the upsurge in progressive efforts to enlist American schools, U.S. corporations, and all levels of government in the promotion of the doctrine that the United States is systemically racist. Progressives, who generally favor civic action, have responded with indignation, derision, and calumny. The vituperation they direct at conservatives suggests that progressives either think the campaign to entrench systemic racism as the conventional wisdom stands above all criticism or suspect that it is fatally vulnerable to scrutiny.

Progressives greet the conservative defense of old-fashioned liberal ideas like toleration, individual merit, and equal treatment for all with ad hominin attacks. They reproach conservatives for daring to question the tenets of critical race theory, Ibram X. Kendi’s “antiracism” catechism, and Robin DiAngelo’s pronouncements on “white fragility” — a body of controversial opinions that many progressives believe prove racism is latent in the American spirit and woven into nation’s institutions. And, as is common on both sides of the political spectrum these days, they divide the world into Us and Them, seeing theirs as the party of compassion and benevolence while casting conservatives as the party of the benighted and the bigoted.

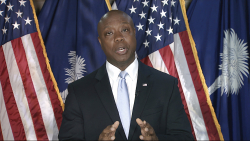

Consider New Yorker staff writer Jelani Cobb’s recent denunciation of South Carolina Republican Sen. Tim Scott.

On April 28, Scott gave a forceful but measured response to President Biden’s address to Congress earlier that evening. Scott said that Biden “seems like a good man,” and “[h]is speech was full of good words.” Scott commended the president’s goals: “He promised to unite a nation. To lower the temperature. To govern for all Americans, no matter how we voted.” But the senator criticized the president and the Democrats he leads for betraying that promise. Instead of adopting “policies and progress that bring us closer together,” according to Scott, “the actions of the president and his party are pulling us further apart.”

Scott noted that in 2020 “under Republican leadership, we passed five bipartisan COVID packages.” But under the Biden administration, the senator lamented, the Democrats eschewed cooperation: “They spent almost $2 trillion on a partisan bill that the White House bragged was the most liberal bill in American history!”

The Democrats’ uncompromising stance on the COVID package and their proposals for massive spending on infrastructure – redefined, Scott observed, to downplay roads, bridges, airports, and the power grid and to feature social programs — were not, in his view, the most urgent breakdown of democratic comity. “Nowhere do we need common ground more desperately,” he declared, “than in our discussions of race.”

No stranger to discrimination in his youth, Scott called attention to the racism now directed at him from the left: “I get called ‘Uncle Tom’ and the N-word — by ‘progressives’! By liberals!” Such invective, he continued, is encouraged by our schools where, as a century ago, “kids again are being taught that the color of their skin defines them — and if they look a certain way, they’re an oppressor.” While rejecting the charge that the United States is “a racist country,” Scott stressed that we must fashion just policies to combat the racism that persists: “It’s backwards to fight discrimination with different discrimination. And it’s wrong to try to use our painful past to dishonestly shut down debates in the present.”

Scott’s opinions about race would, within living memory, have been commonplace among civil rights activists. Yet Jelani Cobb characterized them as despicable. Indeed, in “The Republican Party, Racial Hypocrisy, and the 1619 Project,” which appeared in late May in the New Yorker, Cobb as much as called Scott an Uncle Tom. “[T]he sole Black Republican in the Senate was speaking on behalf of a Party that, under the increasing influence of the far right, has embraced a brand of belligerent and overt racism that was naïvely thought to have been banished from American politics,” wrote Cobb, who in addition to his position at the New Yorker is a Columbia University journalism professor. “This was a stunning display of cynicism, even by the standards of the current G.O.P.,” Cobb added, and “not the first time that Scott’s race had been utilized so disingenuously.”

Denying Scott’s agency and reducing him to a prop in a conspiracy to perpetuate oppression, Cobb maintained that Republicans have adopted the pose of “anti-anti-racists” in order to conceal their true purpose, which is “to launder the G.O.P.’s reputation” and “facilitate the more overtly racist portions of the party’s agenda.”

In Cobb’s telling, Donald Trump’s September 2020 executive order (reversed by Biden on his first day in office) prohibiting the promotion of “race or sex stereotyping or scapegoating in the Federal workforce or in the Uniformed Services” is a prime example of the Republican campaign to promulgate “wholesale lies” about the past and present. So too, according to Cobb, was Sen. Tom Cotton’s bill to “prohibit the use of federal funds to teach the 1619 project by K-12 schools or school districts” as well as the decision by the board of trustees at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to grant Nikole Hannah-Jones, lead author of the 1619 Project, a five-year appointment rather than tenure.

These actions, Cobb maintains, spring from a racist determination to suppress the reality of racism in America. That’s absurd.

Contrary to Cobb’s suggestion that it was George Floyd’s killing last year that provoked a long overdue reckoning with the nation’s racist legacy, the nation has been more or less continuously reckoning with its racist past since the Supreme Court’s unanimous 1954 decision in Brown vs. The Board of Education, which declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional, and the landmark federal legislation of the 1960s — the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. In the wake of these government actions, and thanks to schools, national media, and popular culture, most Americans under the age of 70 grew up understanding that the evil institution of slavery is an indelible part of American history, that the nation had made great progress in eliminating discrimination on the basis of race under law, and that serious work remains to be done.

Conservatives oppose a peculiar set of ideas — championed in different ways by Kendi, DiAngelo, and Hannah-Jones — that had been in circulation for decades but came to the fore amid the peaceful protests and violent riots of late last spring and summer. According to the doctrine of “systemic racism,” discrimination on the basis of race is not merely still present, but a pervasive and defining feature of the existing political order and the contemporary American experience. The doctrine teaches that all white people are unjust beneficiaries of power and privilege that derive from slavery and segregation; that free speech, due process, and equality before the law must be suspended in order to ensure proportionate group representation in key institutions and professions for blacks and other historically discriminated-against minorities; and that to question any part of this doctrine is itself an expression of racism.

To be sure, Republicans have not always spoken or acted as carefully as they ought in countering the promulgation of the dogma of systemic racism by schools, corporations, and the federal bureaucracy. Conservatives should not seek to ban the doctrine. Understanding the claims of systemic racism and that many Americans embrace them is part of being an informed citizen. At the same time, conservatives — and all who honor the nation’s constitutional heritage — rightly oppose efforts by schools, corporations, and government bureaucracy to espouse, advocate, inculcate, or demand assent to the dogma of systemic racism.

The cultivation of an informed citizenry, one in which each individual is encouraged to think independently and listen to fellow citizens’ contending points of view may even prove to be a form of civic action capable of forging alliances between right and left.

[ad_2]

Source link