[ad_1]

Last week, a Newsweek reporter filed a dispatch on a Senate bill that would lead to the creation of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Latino in Washington, D.C.

At the time, the vote seemed almost pro forma. A similar bill had sailed through the House in July, and many expected the Senate bill to pass by unanimous consent (Senate parlance for a voice vote). The bill would then move to the White House. And that, reported Newsweek, “would leave President Donald Trump to get it across the finish line before his term ends.” No small irony given Trump’s often disparaging remarks toward Mexicans, and the fact that his most significant nod to Latino culture in recent years was having himself photographed with a taco bowl.

But the bill was not sent to the White House. Last Friday, Sen. Mike Lee of Utah blocked the legislation for the new museum, in the interest of “national unity and inclusion” since, he said, “hyphenated” identities result in the “balkanization of our national community.”

“It sharpens all those hyphens into so many knives and daggers,” said Lee in a Senate floor speech intended to stop the motion. (Voice votes can be held up by the objections of a single senator.) “It has turned our college campuses into grievance pageants and loose Orwellian mobs to cancel anyone daring to express an original thought.”

After which the guy calling out cancel culture proceeded to cancel the museum. In the process, he also canceled a museum devoted to women’s history.

A view of the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries building, which has been floated as a possible site for the National Museum for the American Latino.

(Smithsonian)

Part of Lee’s rationale stems from his notion that the Latino experience doesn’t rise to the level of a federally funded museum on the National Mall. Institutions devoted to African American and Native American history were different, he said, because those groups were “essentially written out of our national story and even had their own stories virtually erased.”

Never mind that a Smithsonian Institution task force published a report in 1994 about the ways in which Latinos were presented at the Smithsonian’s branches. Its title? “Willful Neglect.”

“The Institution almost entirely excludes and ignores Latinos in nearly every aspect of its operations,” said the report. The task force “could not identify a single area of Smithsonian operations in which Latinos are represented.”

This failure, the report concluded, perpetuated “the inaccurate belief that Latinos contributed little to our country’s development or culture.”

New Jersey Sen. Robert Menendez, who wrote the Senate bill — and has been trying to get the measure passed for years — noted as much in his response to Lee. “We have been systematically excluded,” he stated, “not because this senator said so, but because the Smithsonian itself said so.”

Sen. Bob Menendez of New Jersey authored a bill to launch a National Museum of the American Latino.

(Associated Press)

To be fair, the Smithsonian has made many improvements since the 1994 report. In 1997, the Smithsonian Latino Center was established, which has led to increased representation, with the hiring of almost a dozen Latino staffers across its institutions, and helped diversify permanent collections. In 2022, the center plans to inaugurate a dedicated gallery to U.S. Latino history within the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

But representation nonetheless remains a challenge. Over the last 17 years (the period for which exhibition archives are available online), the National Museum of American History has featured only half a dozen exhibitions around Latino themes. Two of those were about the late Cuban singer Celia Cruz. The most recent exhibition, about the Bracero Program, closed in 2017 — three years ago.

The Smithsonian’s arts institutions have a similarly complicated legacy. Between 1958 and 2016, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery staged only seven exhibitions devoted exclusively to the work of U.S. Latino artists, according to an exhibition archive published online. Only three of those were solo shows — for Argentine-born print maker Mauricio Lasansksy, as well as Mexican American artists Luis Jimenez and Jesse Treviño.

“Fiesta Jarabe,” a sculpture by Luis Jimenez at Otay Mesa, near the Mexican border. The artist is one of the few Latino artists to ever have a solo show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

(Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

In 2010, the museum hired scholar E. Carmen Ramos as curator of Latinx art (she is also acting chief curator) and she has diligently expanded the presence of Latino artists at the museum through exhibitions on urban photography and the Latino presence in American art. She also organized the ongoing exhibition of Chicano graphics, which will return to view once the museum reopens.

But one curator can’t be expected to undo decades of neglect. The Jimenez and Treviño shows were in 1994 — 26 years ago — which means that an entire generation of humans was born and has grown into adulthood without seeing a solo show by a U.S. Latino artist at the museum.

And forget about women. No Latina had a solo show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in the period examined. (Women in general fare poorly. More than half a dozen artists have gotten repeat solo shows at the museum. They are all men.)

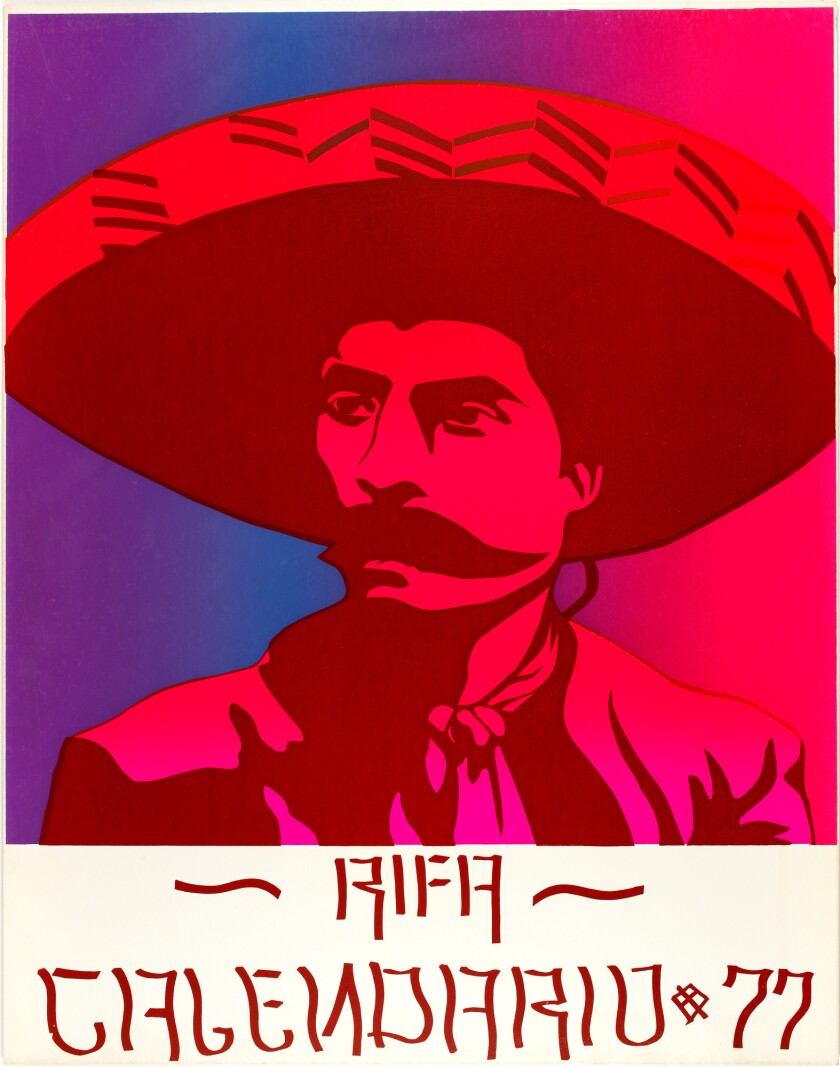

Leonard Castellanos’s “RIFA, from Méchicano 1977 Calendario,” from an exhibition of Chicano graphics at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

(Mildred Baldwin / Smithsonian American Art Museum)

The National Gallery of Art — which is not connected to the Smithsonian but lies only half a dozen blocks away — is much farther behind. To review its exhibition program is to see a museum so wedded to Europe it makes you wonder if the curators somehow never made it on the boat that brought everyone else to the New World.

I combed through the gallery’s online exhibition archives dating back to 1971. In 49 years, the museum has had five special exhibitions exploring Latin American art. Five of these were shows of pre-Columbian art; one featured paintings by Diego Rivera. In the story of art as told by the NGA, U.S. Latinos don’t exist and Latin America is a place that pretty much only exists in a distant past. The last of these shows was held in 2004 — one adolescent lifetime ago.

The NGA’s archives go back to 1941, but I stopped researching at ’71 because it’s the year of my birth. And also because the lack of representation was making me despondent.

I’ll be honest: For a time I was ambivalent about a Smithsonian devoted to Latino history. Latin American history and Latino history are inextricably connected with U.S. history. The entire Southwest — including Utah, the territory Lee represents — inhabits land that was once part of Mexico. And, to me, it’s important that that story be told as part of U.S. history in institutions like the Smithsonian.

Lee said as much in his comments last week, noting that if these stories were being “under-represented at the Museum of American History, that is a problem.”

It is indeed a problem — but probably not for the reasons Lee imagines (all that Orwellian canceling!).

There is a vacuum when it comes to the representation of Latinos in U.S. culture and that vacuum gets filled by figures like Trump, who regularly vilifies Latinos, describing Mexican immigrants as criminals and “rapists.” As I’ve written in the past, the cultural arena offers little to counter to these depictions: it’s either a steady diet of stereotype (maid and drug trafficking roles in Hollywood movies) or just straight-up invisibility.

Late last year, a gunman in Texas drove hundreds of miles to El Paso to kill “as many Mexicans as possible.” Nearly two dozen people paid for the cultural vacuum with their lives.

California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra was an early proponent of a national museum for Latinos when he was a congressman.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

Years of task forces and studies and well-intentioned committees have chipped away at the problem, but a prominently placed museum in the capital would offer a visible and compelling counter-narrative — one that would be accessible to a broad swath of the U.S. public.

Xavier Becerra, who prior to serving as California attorney general was a U.S. representative for California, was an early proponent of the museum. “Millions of people are visiting the Mall to learn about what it means to be an American,” he told the National Journal in 2013, “and there is this absence of the full richness of what it means to be American.”

On Monday, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus sent a letter to Senate leaders, urging them to include the legislation for the museum in a spending bill that Congress is currently trying to pass.

“With a 500-year history that predates the founding of the country, Latinos have been a part of the American story since the beginning,” reads the letter, “but to see the galleries and exhibits throughout the Smithsonian, one would never know that to be the case.”

It’s an absence that Lee willfully neglects. And certainly, he should know better. Latinos make up almost 15% of his constituency in Utah. In fact, on his website, you can find the transcript to his floor speech published in English. It is also available in Spanish.

[ad_2]

Source link