[ad_1]

“Does anyone else here struggle with imposter syndrome?”

Jamie posed her question to the Precision Nutrition Coaches Facebook Group, wondering if other coaches ever felt the same way.

“I know I am certified and have the information and skills that I need to coach,” she wrote. “But I have that persistent voice in my head that tells me I’m not qualified enough.”

In minutes, Jamie’s post was flooded with responses.

The dozens of answers she received amounted to a collective “Yes!”

Jamie definitely isn’t alone. And if you feel the same way, neither are you.

The good news?

For every coach who struggles with imposter syndrome, self-doubt, and insecurity, there’s also one who’s overcome it (or at least learned to effectively manage it.)

In this article, we’ll pull back the curtain on imposter syndrome, sharing the stories—and strategies—of coaches who’ve been through it. And we’ll offer helpful advice from our own experts.

Then you’ll be on the road to conquering your self-doubt, leveraging your own expertise, and coaching with confidence.

(Side note: Yes, we know most dictionaries spell it “impostor.” But because it seems more people use “imposter”—a spelling that’s also considered acceptable—we chose that version.)

++++

In the Precision Nutrition Level 2 Certification, there’s a lesson we call “The Secret.”

In this lesson, we ask our students:

Do you have a secret angst or worry about coaching?

When you think about that secret, what is it like? How does it make you feel?

Coaches aren’t required to share their secrets with us, but lots do.

And, considering the Level 2 Certification is an advanced Master Class, their answers might surprise you.

According to Precision Nutrition Level 2 Master Coach Jason Bonn, “By far the most common response is about imposter syndrome, stemming from not ‘knowing enough’ or not being ‘good enough.’

“Almost everyone falls somewhere on the spectrum of not feeling ‘enough’ in some way,” says Bonn. “Though some feel it much more deeply than others.”

(The second most-common secret? Concerns about one’s own body or physique. Read: Am I fit enough to be a trainer?)

What is imposter syndrome?

Imposter syndrome is the nagging feeling that you’re somehow not good enough to do what you’re doing and that eventually, someone will find out.

This often-unfounded yet persistent feeling can interfere with your confidence, mess with your coaching skills, and steal the joy and passion that led you to do this work in the first place. It might even stop you from coaching altogether.

How do you overcome imposter syndrome?

To find out, we spoke with six PN Certified coaches who’ve been through it themselves, and sought advice from our own top coaching experts.

Here are five proven strategies to try.

Strategy #1: Be a coach, not an expert.

Previously a successful chef, Robbie Elliott made a career transition and became a coach in his mid-30s. But the change came with a ton of anxiety.

He feared client questions and positively dreaded having to say the words, “I don’t know.”

“When you don’t know the answer to a question, and you’re supposedly the voice of the professional, it can be really deflating,” says Elliott.

“There were times early on in my career that I would get things wrong simply because I wasn’t sure, but I really wanted to give an answer.”

In time, Elliott learned that “trying to be the person who knows everything is actually really detrimental. Being authentic and honest, and then dedicating yourself to finding the answer is way, way better.”

Elliott’s new mantra? “I might not be the perfect coach, but I can be the dedicated coach.”

Srividya Gowri had a similar revelation. Once hyper-concerned about being perceived as “The Expert,” Gowri eventually realized that “I don’t need to be the expert. I don’t need to know everything. If my clients are getting the results they want, that’s what matters.”

This mental shift relieved Gowri’s imposter syndrome—and changed her coaching style.

“I’m not setting huge expectations and saying ‘I’m this perfect coach and I’m going to get you these results,’” she explains. “No, I’m saying ‘We’re going to try things together, and experiment, and see what works for you’. This eases the pressure for both me and my clients.”

Put it into action

In the Precision Nutrition Level 2 Certification program, coaches are taught that while you may be the expert on nutrition, the client is the expert on their experience.

Here are a few ways you can put this into practice.

1. Assume nothing.

Ask about and confirm every single proposition and assumption you make with a client. Be clear that you’re using a working hypothesis rather than an “expert pronouncement.”

For example, you might say,

“OK, here’s my take on things. Did I get that right?

“Based on my experience, here’s what I’m guessing will work for you, but we may need to test it and see how it turns out.”

“It sounds from what you’re saying like _____ might be a good next action?”

2. Be honest if you don’t know something.

Saying “I don’t know but let’s find out together” is powerful stuff.

If your client’s experience is different than yours, level with them.

For example, you might say: “I’m going to be truthful with you. I don’t know much about cancer survivors. But I’ve got a good toolbox of things, and I’m prepared to collaborate with you and do what it takes to become informed. I’m on your team all the way. We’ll work through this together.”

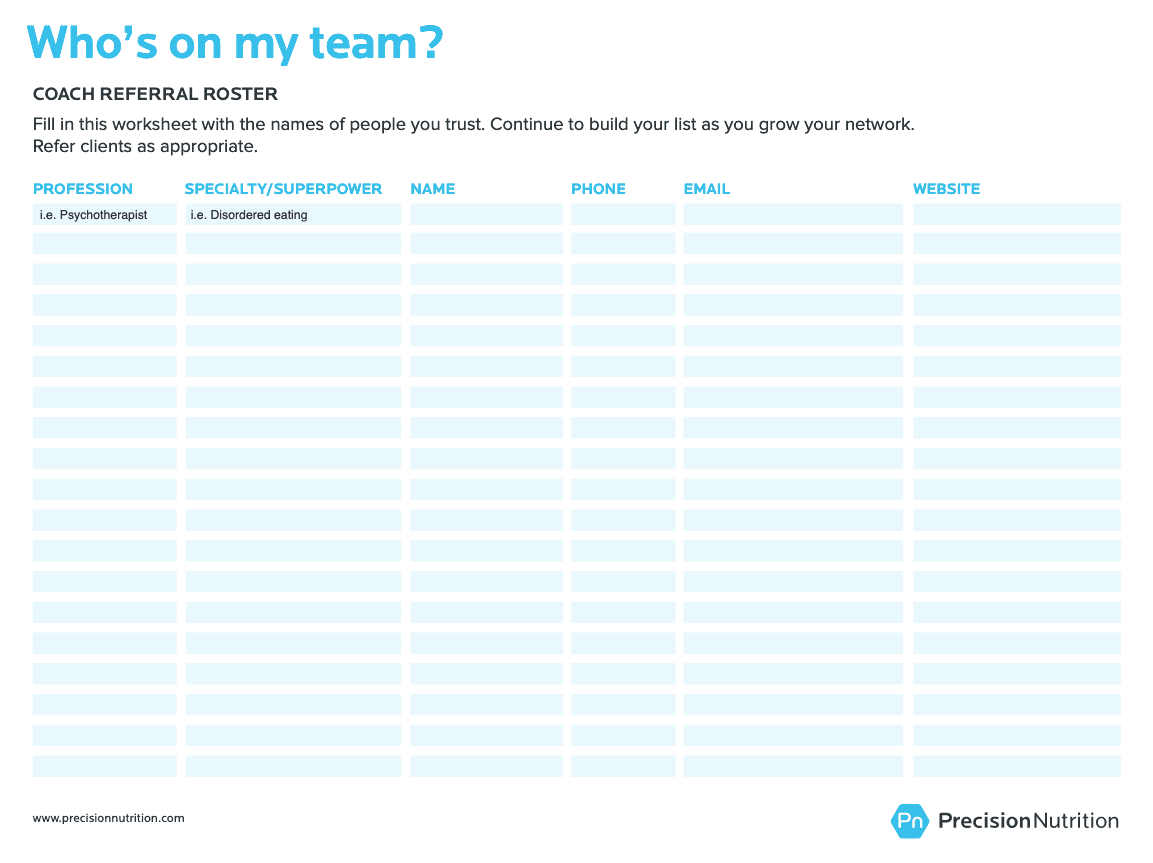

3. Build a referral network.

You don’t need to be (nor should you be) the expert on absolutely everything.

Building up a referral support network can give you an opportunity to help your clients even when their needs are outside your scope—by referring them to someone who can legitimately help. (Start building your referral roster by clicking the image below to get the downloadable form.)

Strategy #2: Gather feedback, intelligently.

Feedback—both positive and negative—can be an effective antidote to imposter syndrome.

For example, Kay Sylvain had been really hesitant to put her qualifications into action and start coaching clients. But once she did, she found that their positive feedback helped a lot.

“Getting positive feedback reminded me that sometimes the way we view ourselves is not necessarily how others view us,” she says.

But even negative feedback can be helpful too.

“Maybe you do need more time, experience, knowledge, or skills to be the kind of coach you want to be,” says Dr. Krista Scott-Dixon, director of curriculum at Precision Nutrition.

“Imposter-syndrome-type anxieties can reflect a completely valid urge towards self-improvement. The problem with anxiety is that it lives in your head, thriving on isolation and shame.”

Getting clear on how and where you have room for improvement can ease the anxiety.

Take Greg Smith. In his early days as a coach, Smith was terribly worried about coaching “right,” trying to avoid mistakes at all costs.

Now, instead of worrying about doing the wrong thing, or not doing enough, he gathers feedback (or “data”) he can use for small, incremental improvement.

“When my clients are trying something new, I tell them the worst thing that happens is you learn what didn’t work for you. And then you get data to help you do it better or differently next time. The same is true for ourselves,” he says.

According to Robbie Elliot, this “data gathering” approach might be best paired with an added step: data filtering.

“I try to be obsessively open to feedback. But if you take every little bit of feedback to heart—including from random people on the internet who don’t know you—you’ll be questioning yourself all the time.

Instead, Elliott concentrates on deliberately sourcing feedback from people he trusts. That includes his family, a close group of friends and colleagues, and his PN coaching mentor, Jason Bonn.

Elliott takes critical feedback from that group very seriously. “I know their values, and they know mine,” he says. “I trust they will tell me if I need to look at something or do something better. Their feedback keeps me accountable.”

Put it into action

It’s hard to actively solicit feedback, and use it constructively—if you’re deathly afraid of screwing up.

To help you become more receptive to feedback, try an approach that we at PN call “feedback, not failure.”

First, imagine this. You’re walking on a rocky surface—maybe a beach, or a dry creek bed, or a hiking trail.

If you step on a rock, and it shifts, did you fail?

No.

You just got important information about the next thing to do—try another rock.

You got feedback.

Instead of treating any mistakes or slip-ups as failures, try to see them as feedback, and approach them with curiosity.

For example:

- Look at the choices you make, and notice what happens.

- What information did you get? What insight? What data?

- What does that feedback tell you about what you could do next, or change in the future?

- Or keep the same? Or do less/more of?

- What happens when you take action X? What happens when you do Y? What about Z?

Get rid of the words “good” or “bad” and substitute “interesting” or “useful,” as in: “Well, that’s interesting,” or “That’s useful to know.”

With this mindset, you can start to treat all feedback as neutral information that you can use to make decisions—with less fear of failure.

Strategy #3: Question your thoughts and assumptions.

Have you ever felt like other coaches, practitioners and professionals have more or better qualifications than you?

That’s exactly how Heather Lynn Darby used to feel. Earlier in her coaching journey, she compared herself to “other professions that are licensed.”

In particular, she worried that nutrition coaching would be seen as “less legitimate” than a registered dietician (RD), doctor, or psychologist. Maybe clients wouldn’t respect her credentials or see the true value she had to offer.

Rather than letting her assumptions take over, Heather Lynn practiced some critical thinking.

“I asked myself, ‘Why would someone come see me instead of a registered dietician? What’s the unique value I bring that’s different from an RD?‘”

She came up with loads of answers: like being able to offer more personal and frequent contact to clients, something clinicians like RDs aren’t always able to provide their clients.

“That differentiation helped me discern my unique value and concentrate on that,” she explains.

In addition, Heather Lynn challenged her fears by asking: “Is this true?”

“The process goes like this: If you’re assuming something negative about yourself or your situation, ask yourself the question: ‘Is that true? Are your achievements fake? Did you or did you not complete those certifications? Was it really just luck that got you where you are now?’”

You might discover the answers by reflecting on your past.

That’s what Srividya Gowri did.

In her early years as a coach, Gowri felt “like a fish out of water. I worried, do I know everything? Do I have the talent and skills to actually help someone who’s so different from me? What if it doesn’t work? Are people going to call me out and say, ‘Hey, you’re fake. Your coaching didn’t work on me?’”

To challenge her fears, Gowri took a step back. She reflected on all the changes she’d made in her life, the challenges she’d worked through, and the successes she’d had.

This led to a profound lightbulb moment.

“When I looked back I realized: You know what, maybe nutrition coaching is new for me, but learning something new is not new. I have learned. I have succeeded. I have been able to do very well. And there’s a lot I’ve overcome with grit and resilience.”

Put it into action

When uncomfortable thoughts or feelings crop up, try writing them down, says Karin Nordin, PhD(c), behavior change coach and curriculum advisor to Precision Nutrition.

“You might find it helpful to explicitly write down: What is it that you think makes you an imposter?”

Once your thoughts and assumptions are on the blank page in front of you, consider them critically.

“Ask yourself, ‘Do I actually believe that’? From there you can start that metacognitive process to consider and challenge your own thoughts.”

As an added step, try taking a page out of Gowri’s book. Make a list of your previous accomplishments and a list of challenges you’ve overcome. How did you make it through those difficult times? What strengths, skills or assets have those experiences given you?

By looking back and re-familiarizing yourself with your own history, you might realize you’re more prepared and capable than you thought.

Strategy #4: Seek improvement and mastery rather than trying to avoid failures.

Do you tend to focus on avoiding mistakes? Or on making improvements?

According to Nordin, if you have imposter syndrome, your focus is likely on avoiding mistakes—as opposed to being awesome.

“Research suggests that people with imposter syndrome tend to focus on performance-avoidance—trying to avoid mistakes—rather than improvement or mastery,” says Nordin.

This can translate to thoughts like, ‘I’m a fraud, I don’t know what I’m doing, I’m afraid of messing up in front of everyone,’ rather than thoughts like, ‘How can I get better at this?’

The solution?

Try to shift towards mastery goals (goals focused on improvement), rather than performance-avoidance goals (goals focused on preventing mistakes).

For Chaquita Niamke, this was a significant mental shift.

Earlier in her career, if Niamke made a mistake with a client, she felt so embarrassed, she didn’t want to show her face. (She even found herself ducking a previous client in the grocery store.)

But in time, she became more focused on working towards her bigger goals and the things she needed to do to get there.

“I know when I have a plan and a process, the imposter syndrome is not as prevalent,” she says.

Niamke also learned to “embrace the road to mastery, with all its lumps and bumps along the way.”

“I came to realize the process is the process,” she adds. “You have to go through it in order to be refined.”

Put it into action

To get out of your imposter syndrome mindset, try shifting your focus towards improving the things you want to master, rather than focusing on avoiding the things you’re afraid of.

To do this, Nordin suggests a “thought bridge.”

“Suppose you think you’re not the best coach right now,” she says. “Rather than saying, ‘I’m not a great coach,’ try telling yourself, ‘I’m not the best coach, but I can get better.’”

From there, Nordin recommends focusing on the things you’d like to improve.

For example, you might say to yourself: “I really want to master motivational interviewing. So in this client session, I’m going to focus on my motivational interviewing skills.”

Or you might say, “I really want to be a compassionate coach. So in this session, I’m going to practice being as compassionate as I can.”

These stepping stones can build a path to confidence, while helping your brain think more productively and creatively.

“After a while, you might say, ‘Hey, I’m a pretty great coach after all, because I’ve worked really hard at it. And I know I can always get better.”

Strategy #5: Put in the reps.

There’s no getting around it.

Gaining confidence, developing your skills, and feeling solid in who you are and what you offer… these kinds of things take time, effort, and experience.

“If you don’t get your reps in, the imposter syndrome just stays there,” says Niamke. “You have to go through it.”

Greg Smith agrees. As a young coach, he constantly worried whether he was “doing it right.” But looking back, he now says, “I practiced coaching just like the clients have to practice their eating habits. It doesn’t happen overnight. You need to put in the reps.”

But sometimes, it can be really hard to get started.

After receiving her PN Level 1 Certification, Kay Sylvain was still hesitant. “I was like, ‘Okay, I passed the test, but I’m not really ready to coach.’”

Her imposter syndrome kept telling her to wait. So she got more certifications and more training.

“And I still wasn’t doing anything with it. Just hoarding knowledge, reading books. I came to a point where I said to myself, ‘Am I really going to start this or am I just going to keep taking courses?’”

Sylvain finally realized that she wouldn’t magically feel confident enough. So she chose to get started anyway.

“I said to myself: Either you’re going to do this, or you’re not,” says Sylvain. “After that, I filed all the paperwork, set things up, and finally started my business in the span of a week.”

Put it into action

“Put in the reps” might seem like obvious advice. But sometimes we forget about it (or don’t take it) because we set unrealistic expectations for ourselves.

For a re-set, try this thought experiment from Dr. Scott-Dixon.

Suppose a client comes to you. They’re about 25 pounds overweight, especially in their midsection.

They tell you they want visible abs.

And they want them in one week.

You try to reason with them. Explain the physiology. Show them examples of other clients so they can set their expectations accordingly.

In turn, your client says, “That’s all well and good for other people. But I’m different. I should be able to get abs in a week.”

What would you think?

You’d probably be shaking your head (at least on the inside).

“If you’re just starting out and expecting to be successful, confident, even perfect overnight, you’re basically asking for ‘abs in a week,’” says Dr. Scott-Dixon. “In other words, you’re not thinking realistically about what it really takes to meet a goal.”

Instead of worrying about whether you’re good enough (or not), get clear about your goals, and set a realistic plan to achieve them.

To get started, try the PN “Goals to Skills to Practices to Actions” method. (We call this GSPA.)

First, take out a piece of paper and write down your goal. Make it as specific and concrete as possible.

Then, reverse-engineer what’s required to achieve that goal. Ask yourself:

- What skills do I need to develop to meet my goal?

- What practices will help me develop these skills?

- What actions do I need to take, and when?

Clarifying what you want to improve will allow you to make progress, and see concrete, measurable improvement as you go.

Bit by bit, progress by progress, rep by rep, you’ll probably stop feeling like an imposter. And you’ll start to see yourself becoming the coach you always wanted to be.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, preferences, and circumstances—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

[ad_2]

Source link