[ad_1]

One year into his tenure as Virginia governor, Ralph Northam stumbled awkwardly into the fraught topic of third-trimester abortions. A freshmen Democratic legislator from Northern Virginia had testified that her new legislation “would allow” an abortion in the case of a woman who was dilating and about to give birth. The delegate later said she’d misspoken – that abortion shouldn’t take place during “a live birth” — which might have been the end of it, but then Northam, a physician by trade, weighed in. While discussing unborn babies that “may” have “severe deformities,” he took the discussion in an ominous direction.

“The infant would be delivered,” Northam explained. “The infant would be kept comfortable. The infant would be resuscitated if that’s what the mother and the family desired, and then a discussion would ensue between the physicians and the mother.”

That “discussion,” presumably, was whether to commit infanticide. Republicans pounced, as the saying goes. The entity that pounced most forcefully was a conservative outlet named Big League Politics, which produced a copy of Northam’s 1984 yearbook page from Eastern Virginia Medical School. It showed a younger Ralph Northam in blackface, standing next to a fellow student in Ku Klux Klan robes. Both students shown are holding beers, over a cheeky caption: “There are more old drunks than old doctors in this world so I think I’ll have another beer.”

Perhaps this stunt was intended as a send-up of racism. But Northam is a Southern Democrat, a descendant of slave owners, and a graduate of Virginia Military Institute, a state school that until recently venerated Stonewall Jackson. He is also a 21st century Democrat, meaning that he immediately groveled for forgiveness. A hint that Northam didn’t fully comprehend the zeitgeist, however, came at his apology press conference. He admitted to dressing up in blackface on another occasion as well, saying it was in homage to Michael Jackson, while offering to moonwalk in front the cameras. His wife wisely interceded at that point.

Demonstrators make their feelings known after a decades-old yearbook photo put Gov. Ralph Northam in critics’ crosshairs.

AP Photo/Steve Helber

Northam’s political career seemed to be disintegrating before our eyes. “Unforgivable!” tweeted President Trump. For once, Trump’s opponents agreed. Here is a partial list of Democrats who called on Northam to resign: Joe Biden; Kamala Harris; Nancy Pelosi; Bernie Sanders; Elizabeth Warren; Cory Booker; most of the Virginia congressional delegation, including both U.S. senators; the Democratic caucus in both houses of the state legislature; former Gov. Terry McAuliffe, along with Doug Wilder, the state’s first African American governor; the Democratic Governors Association; the Congressional Black Caucus; Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring.

“The photo, the conduct it captures, and the racist imagery invoked are all indefensible,” said Herring. “Virginia’s history is unfortunately replete with the scars and unhealed wounds caused by racism, bigotry, and discrimination.”

Freshman Democratic Rep. Jennifer Wexton, who had been in Congress for less than a month, spoke for her party when she tweeted, “The Governor needs to resign. This is a difficult time for our Commonwealth, but I know we can move forward & start healing under the leadership of @LGJustin Fairfax.”

Ah, yes, Lt. Gov. Fairfax, the man waiting in the wings. Fairfax was one the few not piling on. Initially, it was assumed that he was showing restraint, even loyalty to Northam. And why say anything when you’re only hours away from becoming the commonwealth’s second black governor? As it happened, Justin Fairfax had another reason for his reticence: His sudden rise to national prominence had prompted a woman to come forward and accuse him of forcing himself on her sexually.

Fairfax vigorously denied the allegation, as he does to this day, but in a way that made his own behavior the issue. For starters, he lashed out at his accuser in vulgar language in a private meeting with supporters. “F— that a bitch” was the phrase he used, according the NBC News. Then Fairfax released a statement claiming that The Washington Post had previously investigated the allegation against him, but found “significant red flags and inconsistencies” in his accuser’s story. This was untrue, according the Post, and by saying otherwise Fairfax forced the newspaper’s hand. Its editors explained that they had held off publishing because reporters couldn’t find any corroborating evidence. Then, of course, a second woman came forward to say that Fairfax had sexually assaulted her when they were in college.

Stunned Democrats were still processing this information — while anxiously double-checking their copy of the state Constitution to see who was third in line (it’s the attorney general) — when a metaphorically impossible third shoe dropped: A sheepish Mark Herring was forced to admit that he, too, had once dressed in blackface at a party, as rapper Kurtis Blow. The AG preformed the requisite self-flagellation at his own press conference. Although he did not offer to rap (or moonwalk), none of this was funny to Virginia Democrats.

Virginia AG Mark Herring admitted that he, too, had once dressed in blackface at a party, as rapper Kurtis Blow.

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

A lifeline came out of the grave, as it were, from an unlikely source: Harry F. Byrd. In Virginia, governors are limited to a single, four-year term. This didn’t start with Byrd, the longtime Southern Democrat who ran the famed Byrd Machine for much of the 20th century. Term limits here date to 1776. But as political reformers made sweeping election changes across the country in post-World War II America, Byrd’s operation resisted modernizing the state Constitution — just as it resisted allowing African Americans to vote, and for the same reason: to retain power. The upshot of this racist past was that in 2019 Democrats figured that if they stuck with Northam, at least it was only for the rest of his single term. He literally can’t run for reelection.

Seizing upon his party’s dilemma, Northam abruptly changed his story: That wasn’t me dressed up in blackface in the photo after all. I shouldn’t have apologized so quickly. Nobody believed this denial, but what was the Democrats’ alternative? Moreover, even as he rescinded his guilty plea, Northam promised to atone for his sins. His remaining time in office, he vowed, would be spent addressing “some very deep” racial wounds and “ongoing inequities” in Virginia. He was reading Alex Haley’s 1976 novel “Roots,” he told us, and would throw himself into the cause of taking down Confederate statues. In a classic example of chutzpah, Northam credited himself for raising the consciousness of the rest of us. “And so this has been a real, I think, an awakening for Virginia,” he said. “It has really raised the level of awareness for racial issues in Virginia. And so we’re ready to learn from our mistakes.”

It was well past time to retire Robert E. Lee’s statues, in my view. Criminal justice reform is long overdue in Virginia and elsewhere. Northam’s reading lists on critical race theory was irritating, but harmless — or so it seemed. One New York tabloid had fun with the episode with a snarky cover spoofing the commonwealth’s famous motto. But a health crisis was about to explode in New York and Virginia, as it did in the rest of the U.S. and the world. Having a former U.S. Army physician as your state’s chief executive seemed a blessing in the face of COVID-19. Except that Gov. Northam has had other priorities during the pandemic. He has remained a prisoner of his own 37-year-old blackface prank. Virginians of all races are paying the price.

What’s in a Name?

I first moved to Northern Virginia at 16 when my family relocated from California, the state where my mother and I — and all my siblings — were born. It was the middle of my junior year in high school, so I was hardly mollified that my new home state had recently launched an enduring ad campaign: “Virginia Is for Lovers.” Ours was a politically aware household and at first I wondered: Was this slogan, unveiled in 1969, a liberal state bureaucrat’s subversive reference to Loving v. Virginia, the interracial marriage case decided two years earlier by the U.S. Supreme Court? It didn’t seem far-fetched. I was attending a public school in a transitioning county that had only recently been racially integrated.

Sen. Harry F. Byrd (left, with Sen. Olin Johnston) in 1964.

AP Photo/Henry Griffin, File

Why it took so long is a sordid tale, but I’ll sum up: Led by Harry Byrd, Democrats across the South responded to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision with an organized “massive resistance.” In a few cities, including Arlington (where I live now and where my own kids attended public schools), resistance arose to the resistance. But lasting change didn’t come until 1970, when a Republican gubernatorial candidate named Linwood Holton defeated the remnants of the Byrd machine. Once in office, Holton, who was white, escorted his 13-year-old daughter from the governor’s mansion in Richmond to a majority black John F. Kennedy High School.

“Virginia Is for Lovers” had nothing to do with any of that, though the famous motto also originated in Richmond. The campaign came from a local advertising agency, Martin & Woltz. The original idea of the firm’s creative team was a bit less risqué and had more moving parts. In Colonial Williamsburg, for instance, the pitch would be “Virginia Is for History Lovers.” When touting Chincoteague Island, it was to be “Virginia Is for Beach Lovers.” To promote the Commonwealth’s ski resorts the tag line would be “Virginia Is for Mountain Lovers.” Ultimately, David Martin and George Woltz simply streamlined the concept. Unveiled by the state’s tourism board in a 1969 issue of Modern Bride magazine, “Virginia Is for Lovers” is still considered one of the great campaigns in advertising industry history.

But let’s return to that “Virginia Is for History Lovers” line for a moment. In every state, schools and place names are derived from influences ranging from war heroes and politicians to historical events, tribes, geographical features, and myths. I had come from McClatchy High School in Sacramento. One of our rival schools was Hiram Johnson, in honor of California’s great Progressive leader. My junior high was Joaquin Miller, a poet who penned “Song of the Sierras.” Other local schools were named after various dead white males of distinction, including Sam Brannan, John Sutter, and Kit Carson, although the latter two didn’t survive last summer’s marches and statue defacings: Sacramento United School District has announced plans to change the names. In recent years, the district has named schools after Rosa Parks, Susan B. Anthony, and Martin Luther King, which is as it should be, as well as Cesar Chavez, who is both a national and a local hero to Northern Californians.

These schools are sprinkled in with schools named — as they are all over America — after George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and a handful of other demigods. When I left California at 16, several of my friends were attending Sacramento’s newest high school — named John F. Kennedy — the same name as the school Linwood Holton sent to his daughter to in Richmond. My new school, in Fairfax County, Va., was named after George C. Marshall High, a five-star U.S. Army general and Nobel Peace Prize-winning secretary of state. I didn’t realize until long after I graduated that Marshall wasn’t a Virginian. Although he attended VMI, as did Ralph Northam, George Marshall was born in raised in Pennsylvania, in a village named, fittingly, Uniontown.

J.E.B. Stuart High School in Falls Church, Va., underwent a name change — to Justice High School — in 2018 amid objections to honoring a slaveholding Confederate general.

AP Photo/Matt Barakat, File

Other schools and place names in my new home were not as familiar. High schools, streets, bridges, buildings, rivers, and military bases named not just for Thomas Jefferson and James Madison — but also after the likes of Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, and Jefferson Davis. In the city of Fairfax, Route 50 (John S. Mosby Highway) intersects with Rebel Run, the street beside Fairfax High School. Until 1986, its Confederate flag-waving school mascot was “Johnny Reb.” After last summer, many of these other names are also in the process of being changed, including Washington-Lee High School, which my oldest two kids attended. It is now Washington-Liberty.

Some of this is long overdue; some is an overreaction. Although George Washington apparently still makes the cut, the city of Falls Church is erasing slave owners Thomas Jefferson and George Mason from its schools, canceling as it were, the men who wrote, respectively, the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Declaration of Rights — the latter being the foundational document for the Bill of Rights. I’ll be honest: Growing up in California, I’d barely heard of George Mason. That gap in historical knowledge was significant for another reason: I quickly learned after moving to the East that the schools in my birth state weren’t nearly as good as their reputation. I found myself far behind my new classmates in chemistry. My teacher noticed, although her heroic efforts to get me up to speed weren’t enough: I had to repeat the class in summer school. There were other things I didn’t know about my new home, such as why most stores were closed on Sundays (Virginia’s “blue laws,” dating to 1623), and why, exactly, there was a West Virginia.

The short answer was that in 1861, most western Virginia mountaineers held a dim view of slavery and had no desire to secede from the Union. While fishing in West Virginia’s rivers, going to its racetracks, and working construction jobs with carpenters who made the daily trek from Charles Town to Washington, D.C., I learned that these were tough and independent-minded people. I came to admire West Virginians. The coronavirus pandemic has made many Virginians admire them too.

Virginia Is for …

A year ago, when the novel coronavirus came roaring out of central China to every corner of the globe, affluent, educated Northern Virginia seemed a relatively safe haven. As the scourge decimated nursing homes and hospitals in New York and New Jersey, residents in Arlington and other cities on our side of the Potomac River masked up, stayed home, and waited to be tested. And waited and waited and waited.

We watched as Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan alternately reassured his constituents while telling them hard truths. In Richmond, however, the nation’s only U.S. governor who is a trained doctor churned out unhelpful pabulum. It was so bad that his own staff produced a satire of the boss, one obtained by the Washington Post: “We have a 6-phase plan to reopen the state,” it said. “The plan will be a phased plan that we will plan to utilize in phases. The phases will be planned and the planning will be phased. We will move quickly and slowly to open but remain closed. I have created a staff of staffers who will plan the phase and planning while phasing their phases.”

In truth, it was no laughing matter. Virginia’s response to the pandemic was best described as dithering. No one could explain why tests were so hard to come by. One of the deadliest nursing home outbreaks in the U.S. took place in Henrico County, which surrounds Richmond. Eventually more than 50 residents would die in that facility, but as the death toll mounted, neither state nor county officials could even provide testing. When the nursing home turned to a private firm for testing, it was warned by local health officials to be cautious of the tests.

Gov. Ralph Northam poses for an ill-advised maskless selfie last year.

Katz/The Virginian-Pilot via AP, File)

In Arlington, testing was nowhere to be had this spring. Neither was information about testing. Ultimately, a small, family-owned local pharmacy began offering tests. By the time Northam announced he was ordering Virginia residents to wear face coverings in public, he’d stepped on his own message by being photographed mingling with voters in Virginia Beach – sans mask. “I was not prepared because my mask was in the car. I take full responsibility for that. People held me accountable. And I appreciate that,” he said. “In the future. When I’m out in the public, I will be better prepared.”

Northam then set out to explain how his mask order would be monitored — but as the Washington Post noted, he wasn’t prepared for that either. “This is not a criminal matter,” he said. “Law enforcement will not have a role.” Yet his own executive order specifically stated that violators faced potential jail terms. “I’m usually more confused after listening to his news conferences … than I was before I started listening,” said state Sen. William M. Stanley Jr. Stanley is a Republican, but this wasn’t a purely partisan perception.

In mid-May, the Richmond Times-Dispatch uncovered something worse. Because Virginia was lagging so far behind other states in testing — Johns Hopkins University ranked it near the bottom — the Northam administration decided to manipulate its testing data. Two types of coronavirus tests were being administered in this country. The first, the basic viral test, reveals whether a person is currently infected with COVID. The second, an antibody test, detects whether person had the virus in the past and fought it off. Virginia was lumping the two tests together even though they are testing opposite phenomena that engender different medical responses. Co-mingling the data, in other words, is scientific fraud — one that any high school chemistry student could spot — and produces data that Harvard professor Ashish Jha told the Atlantic is impossible to interpret.

“It is terrible,” Jha said. “It messes up everything.”

Almost Heaven, West Virginia…

Viewing the COVID crisis from a wider lens, one reason why so many Virginians covet Marylanders’ governor — and why Americans are comparing their governors with the chief executives of other states in the first place — was the lack of leadership from the man in the White House during this crucible. Donald Trump went from minimizing the virus to boasting incessantly about instituting a belated partial travel ban on China. He demanded public praise from his aides, hogged the camera when he saw Mike Pence getting good press, touted dubious COVID therapies, insulted governors who irritated him, personally hosted superspreader events at the White House, strutted around Walter Reed hospital like a professional wrestler after contracting the disease himself, and repeatedly told states they were on their own.

All of this bungling behavior obscured Trump’s major contribution, which was launching Operation Warp Speed. But when that program produced not one, but two effective vaccines, Trump squandered the moment. It could have been his greatest glory. But instead of marshaling the vast resources of the federal government to get the vaccine distributed and administered, Trump spent his last two months in office playing golf and ranting that he’d really won the 2020 election. Even if a pro-Trump mob hadn’t stormed the U.S. Capitol, this would have been a catastrophic waste of time. And time is what we didn’t have. The virus came roaring back – killing, by the time of Joe Biden’s inauguration, more than 4,000 Americans a day.

A few states and territories rose to the occasion. Money wasn’t the issue, nor was political affiliation. The variable was leadership. Impoverished Puerto Rico — an island, for God’s sake — has administered a higher percentage of the vaccines it received (61.3%) than Virginia. The state with the best record? You guessed it: West (by God) Virginia.

The figures are changing daily, but as I write these words, 81.6% of the vaccines West Virginia has received have gone into people’s arms. On the day Biden was sworn in, Virginia was next to last — and had inoculated a lower percentage of people in its top-tier category than West Virginia had its entire population. Governance matters.

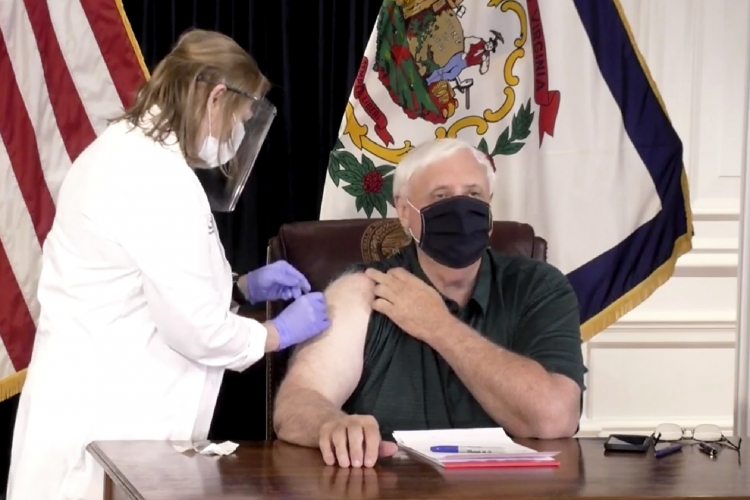

West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice receives his coronavirus vaccine last month.

(State of West Virginia via AP)

The secret to West Virginia’s success was no mystery. Gov. Jim Justice employed the National Guard, FEMA, and a can-do attitude. “We don’t have vaccines in a warehouse sitting on a shelf,” he explained. “We took an ‘all in’ approach. This isn’t rocket science.”

It sounds simple, doesn’t it? Jim Justice campaigned for Trump, whom he called “a friend.” But he didn’t act like him. He didn’t act like Ralph Northam, either. In Virginia, the state government and local counties didn’t take an “all-in” approach. Instead, they set up a systems with several classifications of eligible vaccine recipients and told us to wait our turn. The goal of all this red tape? Fear of running out of a second vaccine, one supposes, coupled with the usual bureaucratic lethargy — and a healthy dose of politics. For one thing, Northam and other state and local officials keep stressing “equity,” a buzzword that is simultaneously an admirable goal and a built-in excuse for inertia. Then there were the interest groups.

When the vaccine was first made available to the public, Fairfax County school officials insisted that its employees go to the top of the vaccine list. Apparently assuming that this meant that schools could reopen, their demand was met. But on Jan. 21, Kimberly Adams, the head of the Fairfax County teachers union, after boasting that she had been one of 5,000 district teachers already vaccinated, announced that her union wouldn’t support a return to full-time in-person learning even next fall – nine months after 22,000 Fairfax teachers and staff will have been vaccinated.

“The union says that all students must also be vaccinated,” noted incredulous parent Rory Cooper, the father of three elementary school-age kids. “Never mind that no current vaccine has been approved for use on children under the age of 14. Adams also wants 14 days of zero community spread. Neither of these goals is likely to occur this calendar year. The excuses pile up faster than the half-inch of snow that typically shuts down school operations.”

Although he hasn’t criticized the teacher unions, in fairness the governor has urged school districts to open. So the problem isn’t that his heart is in the wrong place; it’s that his mind is elsewhere: Urging Virginians to be “patient” while waiting for their vaccines and schools to open, he’s been pushing an unrelated agenda that includes legalizing marijuana, abolishing capital punishment, removing more statues and monuments and renaming more buildings.

Across the border, Gov. Justice has been all about one thing: Getting his people immunized and back to school and work. After dispensing all the vaccines they received – and clamoring for the feds to send more — Justice ordered West Virginia’s elementary and middle schools – and some high schools — to open on Jan. 19. The state’s teacher unions, both the NEA and AFT, sued unsuccessfully and all but three of West Virginia’s 55 counties have complied.

In a Wednesday interview on CNN, Jim Justice made a point of speaking respectfully of both Donald Trump and Joe Biden — and he certainly didn’t criticize Ralph Northam or any other governor – but he did say that he believes his state’s success should be rewarded with increased doses of the vaccine. “I’m sure everybody’s trying their hardest and everything, but we just need to try a little harder,” he said. Then he added this: “I really believe we could vaccinate every person in our state 65 and older and we could get it done by Valentine’s Day, February 14.”

In other words, West Virginia is really the state for lovers. Doers, too.

Carl M. Cannon is the Washington bureau chief for RealClearPolitics. Reach him on Twitter @CarlCannon.

[ad_2]

Source link