[ad_1]

By Michael Hurley, CBS Boston

(CBS Boston) — It’s a bit of a paradox, really, that the longer you stick around, the harder it is to stand out.

That is to say, when your accomplishments surpass levels that had previously never been imagined, and when you outright refuse to go away, thus adding to that previously unfathomable list of accolades, it all somehow reaches a point where it can no longer be properly digested. Not by the human mind, anyway. The baffling numbers and records may begin as awe-inspiring, only to quickly turn into wallpaper.

That hypothesis is relevant this week, of course, because Tom Brady is playing in the Super Bowl. Again. For the 10th time in 20 years.

Tom Brady is old, we get it. Tom Brady wins a lot, we get it. Tom Brady Tom Brady Tom Brady. Enough. We get it.

It’s understandable if the football fans — be they die-hards or casual followers — have grown sick of hearing about this one individual. And yet, while it may seem like an antithetical notion … it’s entirely possible that not enough is being said about him.

Given the nature of this violent sport, this is all not supposed to happen.

Given the designs of a league dead set on parity, it’s not supposed to happen.

Given the sheer difficulty of simply winning football games with such unprecedented consistency, it is not. Supposed. To happen.

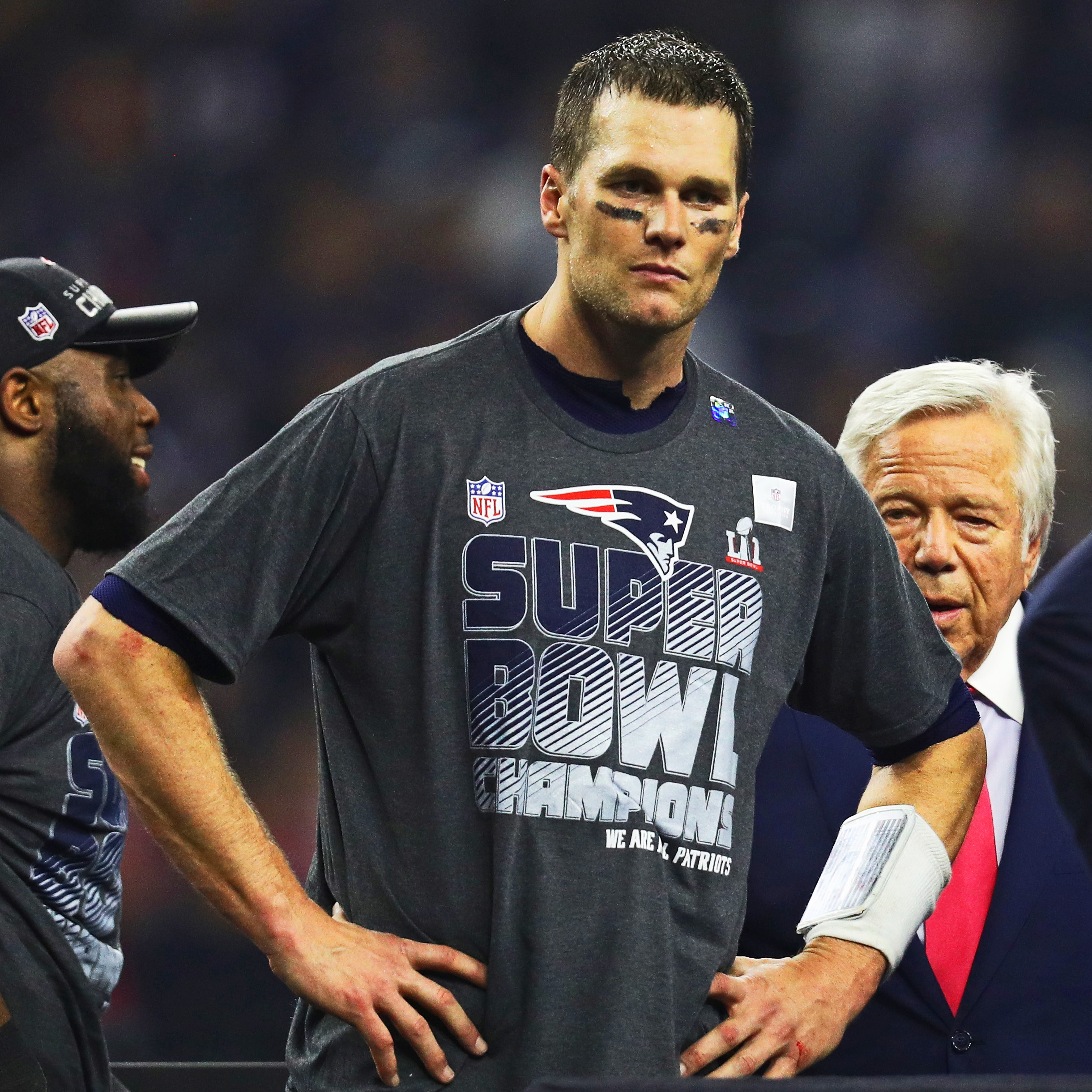

Tom Brady celebrates after winning the NFC Championship Game. (Photo by Stacy Revere/Getty Images)

As we know though, it’s most certainly happening. Already a winner of six Super Bowls, Brady will be gunning for one more on Sunday night. Joining a new team for the first time in his professional life didn’t stop him from reaching this point, nor did a pandemic that drastically limited the amount of work that could take place with his new teammates prior to the start of the season.

When it comes to the greatest winner in football history, minor inconveniences were simply not going to stop him from getting what he wants. Nothing ever has, and even at 43 years of age, that has not changed.

In that sense, without a preseason or spring camps and OTAs, Brady’s impact upon joining the Bucs was more gradual.

A 7-9 team a year ago, the Bucs started the season with a 7-5 record. They took a bye week to regroup, and they’ve gone 7-0 since.

Now, listen: Yes, obviously, one man cannot win football games by himself. And there have been times throughout Brady’s career where he’s tallied a checkmark in the “W” column thanks to defense, a running game, or special teams play that has, quote-unquote, bailed him out. That’s how things work from time to time.

Yet if you look across his entire career, and you find 230 regular-season wins (44 more than any other QB), and you find 33 playoff wins (17 more than any other quarterback), you at some point have to reckon with the fact that none of this is coincidental. Tom Brady’s teams win because Tom Brady is a winner. And when the person manning the most important position in team sports exudes that level of obsessive fixation on winning, well, the results speak for themselves.

Tom Brady (Photo by Patrick Smith/Getty Images)

The indomitable drive is not necessarily something that can be quantified, but developing it is something Brady stated openly as a goal, way back when he was merely a one-time Super Bowl champion at age 24.

“When you talk to all these people, you realize, ‘Now I know why this guy’s done what he’s done.’ You can see why. There’s a competitiveness, there’s a spirit about ’em,” Brady told NFL Films’ Steve Sabol in a now-legendary 2002 interview. “John Elway makes people feel like that. And he made his teammates feel like that, and his coaches. Everyone else believed in him, and everyone else was like, ‘Hey man, if I’m on your side, we’re gonna win.’ When you’re around people like that, you just kind of feel like, you know, man, I’m sitting next to the man.”

Players can try with all their might to develop that natural presence. But really, you either have it or you don’t.

Even at a young age, Brady had it. That’s how he earned a spot on Bill Belichick’s roster in 2000, and it’s why the head coach didn’t go back to the proven veteran with the record contract in 2001 after Drew Bledsoe recovered from his injuries.

When a player has it, you don’t ignore it. You ride it for as long as humanly possible. Belichick and the Patriots rode it for 19 years.

Tom Brady, Bill Belichick (Photo by Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images)

Through it all, the one constant has been Brady’s insatiable appetite for more. In that same Sabol interview, Brady shared his famous Michigan equipment manager story, a tale he has spun countless times thereafter.

“I had an equipment manager in college, and he had been at Michigan for 25 years or so,” Brady said, starting a story you’ve surely heard by now. “He’s got so many Big 10 rings, I mean, he doesn’t have enough fingers for all the rings he’s got. And he says, ‘You know what? You know, Tom, you know what my favorite ring is?’ And I said, ‘Which one is that?’ And he goes, ‘The next one.’ And that’s what I think. The next one. That’s my favorite.”

At the time, he was the youngest QB to ever win a Super Bowl. But he was already locked in on the next one.

Two years later, he got No. 2. A year later, No. 3. To this day, he’s still the last quarterback to win back-to-back Super Bowls, and he’ll be looking to stop Patrick Mahomes from doing that this year.

And though a Super Bowl “drought” followed that third championship in 2004, the work did not stop.

“You have to have leaders that buy in, and Tom was that guy that held the torch. And it was all the time, from the offseason program on through,” backup quarterback Matt Cassel recently told Sports Illustrated’s Albert Breer. “My rookie year, and this is after his third Super Bowl, where a lot of guys might take it easy, to see the way Tom worked in the weight room, in the classroom, there was no part of Tom that was getting comfortable. There was no going through the motions.”

That work led to two more Super Bowl appearances in 2007 and 2011, both last-minute losses to the Giants. It looked like Brady might not ever get a chance to match his childhood idol, Joe Montana, who won four Super Bowls in his career and carried the legacy of being the greatest of all time for 30 years.

We weren’t wrong to believe that, per se. But we were also fools.

Tom Brady walks off the field after losing to the New York Giants in Super Bowl XLVI. (Photo by Elsa/Getty Images)

In 2013, Brady was sacked 40 times, the second-highest total of his career and the most since his rookie year. Resultingly, many analysts predicted his imminent and precipitous decline. Yet instead of following the path of just about every quarterback in history, Brady believed he could still play at the highest level, and he dedicated himself to improve his mobility.

At age 37, he looked like a new man. His completion rate jumped 3.6 points, he threw eight more touchdowns and two fewer picks, his passer rating climbed more than 10 points, and he cut his sack total nearly in half, to 21. Just eight of those sacks came after Week 7. Pundits who declared him to have been close to the 18th hole of his career prior to that season (and even four weeks into that season) were proven to have been very, very wrong.

Tom Brady after Super Bowl XLIX (Photo by Rob Carr/Getty Images)

Yet even after capturing that elusive fourth title (with a fourth quarter for the ages against a historically great Seahawks defense, when he completed 13 of his 15 passes for 124 yards and 2 TDs), it was not enough for Brady. There was no satisfaction. He walked across the field for a postgame interview that night, his grass-stained game pants still on his legs and a steely look on his face, looking like anything but a man who was basking in the joy of reaching football’s ultimate glory.

He made his dissatisfaction clear when he showed up at Fenway Park to throw out the first pitch a few months later, sporting a giant number 5 on his torso.

Tom Brady throws the first pitch at Fenway Park on Opening Day in 2015. (Photo by Maddie Meyer/Getty Images)

Bill Belichick and Tom Brady at Fenway Park (Photo by Maddie Meyer/Getty Images)

The message was unmistakable. The man had just won a championship for the first time in a decade. But he had not had his fill of winning. His eyes were on No. 5.

He led the league in touchdowns the following season, but his last-gasp work with Rob Gronkowski came up one play short in Denver in the AFC title game. He served his bogus suspension in 2016 and then played arguably the best football of his life for three months: 28 touchdowns, two interceptions, 11 wins, one loss.

Then came Super Bowl LI. It started poorly. It ended with the most historic comeback in Super Bowl history, and an avalanche of records for the quarterback.

Tom Brady holds the Lombardi Trophy after Super Bowl 51 (Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images)

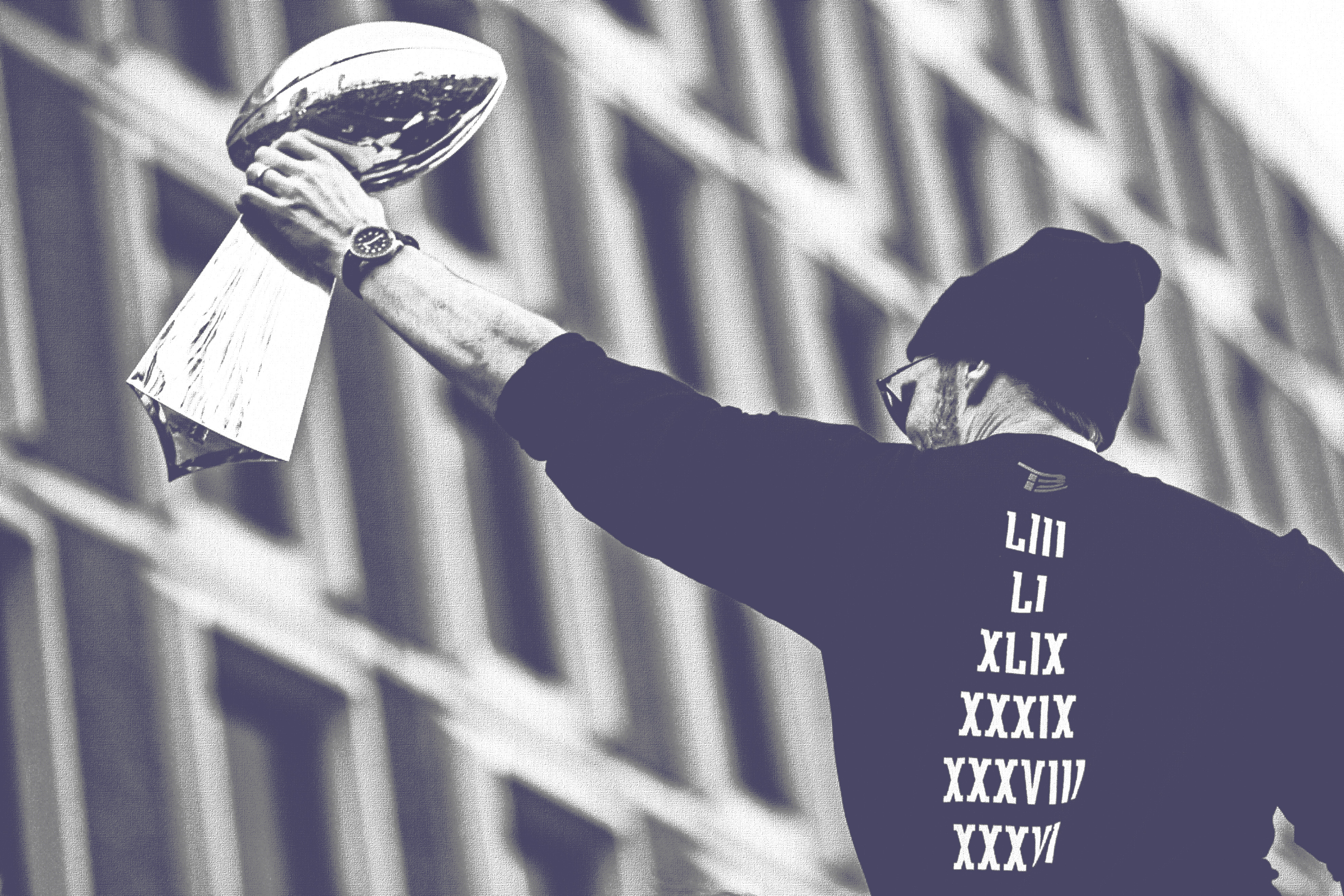

Surely with five under his belt, and the looming 40th birthday ahead, a deep breath and a deceleration would have been in store for most every quarterback. Brady, though, just didn’t believe that it ever had to end. So he won the MVP in 2017 at age 40, set a Super Bowl record for passing yards (in a losing effort), and then … won title No. 6 a year later.

The youngest QB to win a Super Bowl, and the oldest QB to win a Super Bowl, perfect bookends to the best career the sport will ever see.

But as you know, he didn’t want to stop. He might not ever want to stop.

He stayed with the Patriots in 2019, despite an offensive core of skill players that was lacking. He and the defense helped keep things afloat with a 12-4 record, but the team clearly lacked a championship punch. His stats dipped significantly, leading a number of viewers to reasonably assume that at age 42, he was all done.

Brady — are you sensing a theme here? — thought otherwise.

He said farewell to Robert Kraft, Bill Belichick, and the only professional home he had ever known. He received a limited number of offers in free agency, as not every team in the world was eager to commit to a 43-year-old. But the Bucs were smart enough to be willing, and Brady jumped at the chance.

The Buccaneers did have a Super Bowl appearance in their history. As in, one single Super Bowl appearance in their 44-year history. It came back in 2002, a year after Brady’s first title. Brady played in eight Super Bowls and won five after the Bucs’ most recent appearance; the Bucs had participated in just two playoff games in that same span, losing both. Even with that championship in 2002, the Bucs franchise owned a playoff record of 6-9. Brady was 30-11 in the postseason.

To say the Bucs were a losing franchise with a losing track record would be putting it kindly.

But inject Tom Brady into that system, and it only takes about a half of a season for the operation to reach its cruising altitude.

Bruce Arians — who owned a 56-39-1 regular-season record and 1-2 playoff record as a head coach prior to this season — was asked this week about the undeniable drive to compete for championships that lives within his quarterback.

“I think the great quarterbacks all have it. They have the ability to will themselves on other people to make sure that everybody has bought in to the cause. And the cause is a ring. Putting a championship in your trophy case,” Arians said. “So Tom brings that attitude every single day. And it permeates throughout the entire locker room.”

Such an attitude can’t be forced on teammates, especially ones who were in second grade or preschool (or younger) when Brady hoisted his first Lombardi. It has to be natural, which for Brady was no problem at all.

“I think the biggest thing with Tom is he’s just one of the guys. Until you’re with a guy of his stature, you really don’t know his personality on a daily basis,” Arians said. “He is just fantastically one of the guys. And he does such a great job working with younger and older players. It’s like having another coach on the field, and it’s been fantastic.”

Sometimes, that manifests itself in the form of encouragement on the practice field or game day. Other times, it comes in the form of tough love on the sideline, or cursing out a teammate for crying in celebration before the ultimate goal has been reached. Balancing both parts of a good cop/bad cop dynamic with fellow players while not stepping on the toes of the coaching staff would be a tremendous challenge for anyone … except the man who was born to be that leader.

Tom Brady celebrates with Buccaneers teammates. (Photo by Stacy Revere/Getty Images)

Really, the theoretical composite quarterback that Brady idolized 19 years ago didn’t fully exist yet. Brady has now become that person and that leader whom he always envisioned would embody the perfect winner.

“Everyone else believed in him, and everyone else was like, ‘Hey man, if I’m on your side, we’re gonna win.’ When you’re around people like that, you just kind of feel like, you know, ‘Man, I’m sitting next to the man!”

When a wide-eyed 24-year-old Brady said that, the late Sabol — who knew a thing or two about witnessing football greatness firsthand — informed the young QB that he already emitted that special charisma.

“I’ve got a lot of years to catch up to those guys,” Brady replied.

He’s done that, obviously, several times over. He’s won four more Super Bowls than Elway, the man whom he said embodied that spirit. He’s more than doubled up Joe Montana in playoff victories. He didn’t have to prove anything more in 2020, yet he went out with a new team, without Belichick, and without a preseason, and drove the Buccaneers to a Super Bowl — and the franchise’s first playoff win — in 18 years.

Dan Marino, Tom Brady, Joe Montana, Peyton Manning, Roger Staubach, Brett Favre and John Elway are honored as part of the NFL 100 All-Time Team. (Photo by Jamie Squire/Getty Images)

His impact, his drive, his obsession, it’s all undeniable. Of his 19 full seasons in the NFL, 10 have ended in the Super Bowl. That is, quite simply, not possible. He’s won four Super Bowl MVPs; in the two victories where he did not win the MVP, a wide receiver did. In two of the three losses, he threw fourth-quarter touchdowns to put his team ahead, setting a record with 505 passing yards at age 40 in the most recent case.

Perhaps some day, decades from now, we’ll able to encapsulate how significant it all has been, how fantastical and preposterous this career was.

Yet for now, while it’s still taking place, it is simply too much to process. Trying to make sense of it all in real time is akin to trying to cross the highway on foot. This level of winning and this level of success and this unrelenting consistency to end up playing in the Super Bowl in five of the seven years after turning 37 years old — it’s too much.

We can’t process it. We cannot do it. For now, all we can do is watch.

Tom Brady (Photo by Billie Weiss/Getty Images)

You can email Michael Hurley or find him on Twitter @michaelFhurley.

[ad_2]

Source link