[ad_1]

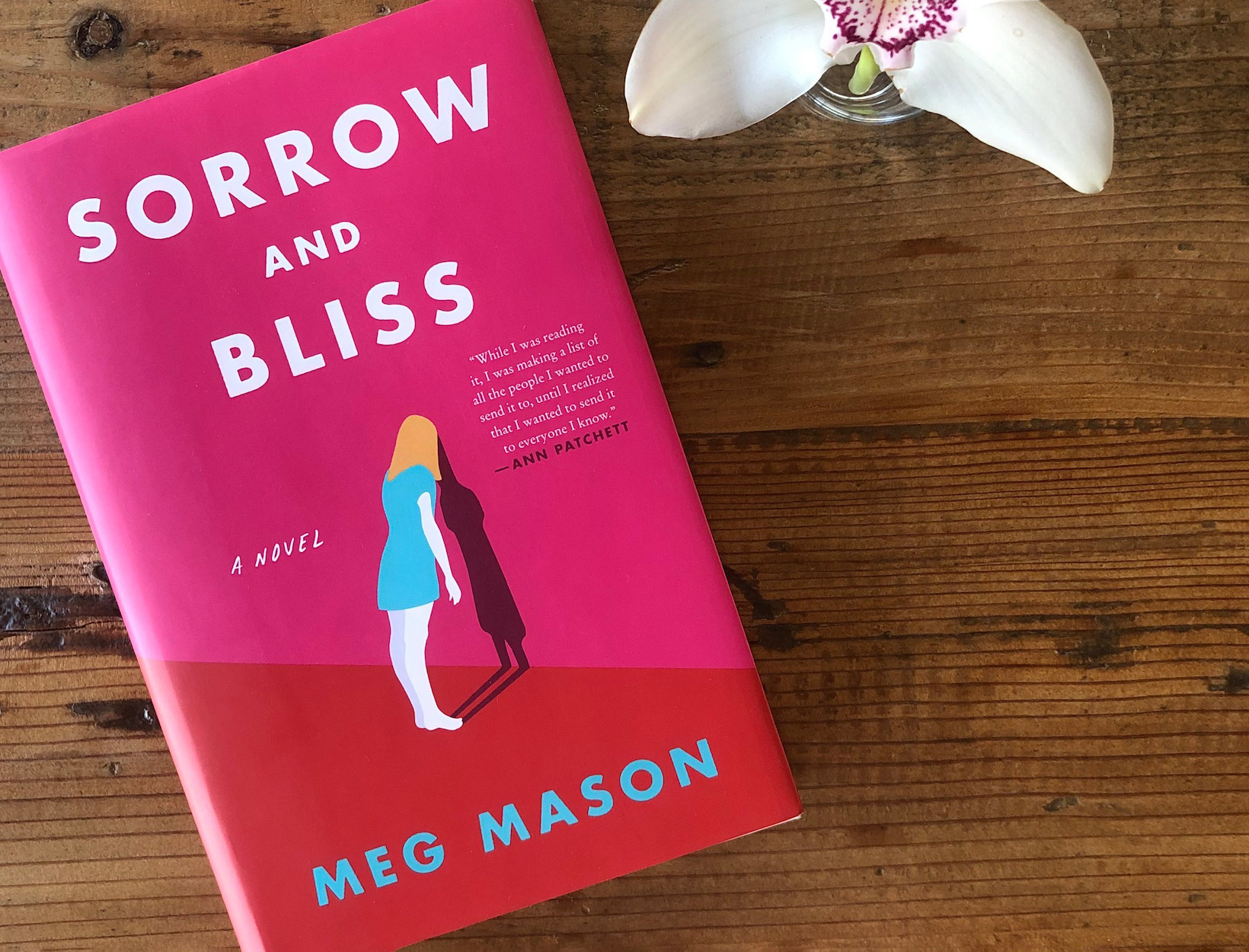

Our March goop Book Club pick, Sorrow and Bliss, is a modern love story that’s funny and dark,

sharp and tender, hopeful and hard to put down. It has a brooding Sally Rooney vibe (but explores a slightly older

and more mature slice of life) with exceptional inner monologue and palpable chemistry among the characters.

The plot is driven by the on-and-off relationship between witty Martha and her charismatic husband,

Patrick, who meet when she’s sixteen—the year before Martha first finds it suddenly impossible, for a spell, to get

out of bed or laugh. The novel opens when Martha is forty and they are seemingly, perhaps, at the end of their

marriage. Or perhaps not.

From Sorrow and Bliss

My father is a poet called Fergus Russell. His first poem was published in The New Yorker when he was nineteen. It

was about a bird, the dying variety. After it came out, someone called him a male Sylvia Plath. He got a notable

advance on his first anthology. My mother, who was his girlfriend then, is purported to have said, “Do we need a

male Sylvia Plath?” She denies it but it is in the family script. No one gets to revise it after it is written. It

was also the last poem my father ever published. He says she hexed him. She denies that too. The anthology remains

forthcoming. I don’t know what happened to the money.

My mother is the sculptor Celia Barry. She makes birds, the menacing, oversized variety, out of repurposed

materials. Rake heads, appliance motors, things from the house. Once, at one of her shows, Patrick said, “I honestly

think your mother has never met extant physical matter she couldn’t repurpose.” He was not being unkind. Very little

in my parents’ home functions according to its original remit.

Growing up, whenever my sister and I overheard her say to someone “I am a sculptor,” Ingrid would mouth the line

from that Elton John song. I would start laughing and she would keep going with her eyes closed and her fists

pressed against her chest until I had to leave the room. It has never stopped being funny.

According to The Times my mother is minorly important. Patrick and I were at the house helping my father rearrange

his study the day the notice appeared. She read it aloud to the three of us, laughing unhappily at the minorly bit.

Afterwards my father said he’d take any degree of importance at this stage. “And they’ve given you a definite

article. The sculptor Celia Barry. Spare a thought for we the indefinites.”

•••

Sometimes Ingrid gets one of her children to ring and talk to me on the phone because, she says, she wants them to

have a very close relationship with me, and also it gets them off her balls for literally five seconds. Once, her

eldest son called and told me there was a fat lady at the post office and his favorite cheese is the one that comes

in the bag and is sort of whitish. Ingrid texted me later and said, “He means cheddar.”

I do not know when he will stop calling me Marfa. I hope never.

•••

Our parents still live in the house we grew up in, on Goldhawk Road in Shepherd’s Bush. They bought it the year I

turned ten with a deposit lent to them by my mother’s sister Winsome, who married money instead of a male Sylvia

Plath. As children, they lived in a flat above a key-cutting shop in, my mother tells people, “a depressed seaside

town, with a depressed seaside mother.” Winsome is older by seven years. When their mother died suddenly of an

indeterminate kind of cancer and their father lost interest in things, in particular them, Winsome withdrew from the

Royal College of Music to come back and look after my mother, who was thirteen then. She has never had a career. My

mother is minorly important.

•••

It was Winsome who found the Goldhawk Road house and arranged for my parents to pay much less for it than it was

worth, because it was a deceased estate and, my mother said, based on the whiff, the body was still somewhere under

the carpet.

On the day we moved in, Winsome came over to help clean the kitchen. I went in to get something and saw my mother

sitting at the table drinking a glass of wine and my aunt, in a tabard and rubber gloves, standing on the top rung

of a stepladder wiping out the cupboards.

They stopped talking, then started again when I left the room. I stood outside the door and heard Winsome telling

my mother that perhaps she ought to try and muster up a suggestion of gratitude since home ownership was generally

beyond the reach of a sculptor and a poet who doesn’t produce any poetry. My mother did not speak to her for eight

months.

Then, and now, she hates the house because it is narrow and dark; because the only bathroom opens off the kitchen

via a slatted door, which requires Radio Four to be on at high volume whenever anyone is in there. She hates it

because there is only one room on each floor and the staircase is very steep. She says she spends her life on those

stairs and that one day she’ll die on them.

She hates it because Winsome lives in a townhouse in Belgravia. Enormous, on a Georgian square and, my aunt tells

people, the better side of it because it keeps the light into the afternoon and has a nicer aspect onto the private

garden. The house was a wedding present from my uncle Rowland’s parents, renovated for a year prior to their moving

in and regularly ever since, at a cost my mother claims to find immoral.

Although Rowland is intensely frugal, it is only as a hobbyist—he has never needed to work—and only in the

minutiae. He bonds the remaining sliver of soap to the new bar but Winsome is allowed to spend a quarter of a

million pounds on Carrara marble in a single renovation and buy pieces of furniture that are described, in auction

catalogues, as “significant.”

•••

In choosing a house for us solely on the basis of its bones—my mother said, not the ones we were guaranteed to find

if we lifted the carpet—Winsome’s expectation was that we would improve it over time. But my mother’s interest in

interiors never extended beyond complaining about them as they were. We had come from a rented flat in a suburb much

farther out and did not have enough furniture for rooms above the first floor. She made no effort to acquire any and

they remained empty for a long time until my father borrowed a van and returned with flatpack bookshelves, a small

sofa with brown corduroy covers, and a birch table that he knew my mother would not like but, he said, they were

only a stopgap until he got the anthology out and the royalties started crashing in. Most of it is still in the

house, including the table, which she calls our only genuine antique. It has been moved from room to room, serving

various functions, and is presently my father’s desk. “But no doubt,” my mother says, “when I’m on my deathbed, I’ll

open my eyes for the last time and realize it is my deathbed.”

Afterwards my father set out to paint the downstairs, at Winsome’s encouragement, in a shade of terra-cotta called

Umbrian Sunrise. Because he did not discriminate with his brush between wall, skirting board, window frame, light

switch, power outlet, door, hinge, or handle, progress was initially swift. But my mother was beginning to describe

herself as a conscientious objector where domestic matters were concerned. Eventually the work of cleaning and

cooking and washing became solely his and he never finished. Even now, the hallway at Goldhawk Road is a tunnel of

terra-cotta to midway. The kitchen is terra-cotta on three sides. Parts of the living room are terra-cotta to waist

height.

Ingrid cared about the state of things more than I did when we were young. But neither of us cared much that things

that broke were never repaired, that the towels were always damp and rarely changed, that every night my father

cooked chops on a sheet of tin foil laid over the piece from the night before, so that the bottom of the oven

gradually became a mille-feuille of fat and foil. If she ever cooked, my mother made exotic things without recipes,

tagines and ratatouilles distinguishable from each other only by the shape of the pepper pieces, which floated in

liquid tasting so bitterly of tomato that in order to swallow a mouthful I had to close my eyes and rub my feet

together under the table.

•••

Patrick and I were a part of each other’s childhoods; there was no need for us, newly coupled, to share the

particulars of our early lives. It became an ongoing competition instead. Whose was worse?

I told him, once, that I was always the last one picked up from birthday parties. So late, the mother would say, I

wonder if I should give your parents a ring. Replacing the receiver after a period of minutes, she would tell me not

to worry, we could try again later. I became part of the tidying up, then the family supper, leftover cake. It was,

I told Patrick, excruciating. At my own parties, my mother drank.

He stretched, pretending to limber up. “Every single birthday party I had between the ages of seven and eighteen

was at school. Thrown by Master. The cake came from the drama department prop cupboard. It was plaster of Paris.” He

said, good game though.

•••

Mostly, Ingrid rings me when she is driving somewhere with the children because, she says, she can only talk

properly when everyone is restrained and, in a perfect world, asleep; the car is basically a giant pram at this

point. A while ago, she called to tell me she had just met a woman at the park who said she and her husband had

separated and now had half-half custody of their children. The handover took place on Sunday mornings, the woman

told her, so they both had one weekend day each on their own. She had started going to the cinema by herself on

Saturday nights and had recently discovered that her ex-husband goes by himself on Sunday nights. Often it turns out

they have chosen to see the same film. Ingrid said the last time it was X-Men: First Class. “Martha, literally have

you ever heard anything more depressing? It’s like, just go the fuck together. You will both be dead soon.”

Throughout childhood our parents would separate on a roughly biannual basis. It was always anticipated by a shift

in atmosphere that would occur usually overnight and even if Ingrid and I never knew why it had happened, we knew

instinctively that it was not wise to speak above a whisper or ask for anything or tread on the floorboards that

made a noise, until our father had put his clothes and typewriter into a laundry basket and moved into the Hotel

Olympia, a bed and breakfast at the end of our road.

My mother would start spending all day and all night in her repurposing shed at the end of the garden, while Ingrid

and I stayed in the house by ourselves. The first night, Ingrid would drag her bedding into my room and we would lie

listening to the sound of metal tools being dropped on the concrete floor and the whining, discordant folk music our

mother worked to, carrying in through our open window.

During the day she would sleep on the brown sofa that Ingrid and I had been asked to carry out for that purpose.

And despite a permanent sign on the door that said “GIRLS: before knocking, ask self—is something on fire?,” before

school I would go in and collect dirty plates and mugs and, more and more, empty bottles so that Ingrid wouldn’t see

them. For a long time, I thought it was because I was so quiet that my mother did not wake up.

I do not remember if we were scared, if we thought this time it was real, our father was not coming back, and we

would naturally acquire phrases like “my mum’s boyfriend” and “I left it at my dad’s,” using them as easily as

classmates who claimed to love having two Christmases. Neither of us confessed to being worried. We just waited. As

we got older, we began to refer to them as The Leavings.

Eventually our mother would send one of us down to the hotel to get him because, she said, this whole thing was

bloody ridiculous even though, invariably, it would have been her idea. Once my father got back, she would kiss him

up against the sink, my sister and I watching, mortified, as her hand found its way up the back of his shirt.

Afterwards it wouldn’t be referred to except jokingly. And then there would be a party.

•••

All of Patrick’s sweaters have holes in the elbows, even ones that aren’t very old. One side of his collar is

always inside the neck, the other side over it and, despite constant retucking, an edge of shirt always finds its

way out at the back. Three days after he has a haircut, he needs a haircut. He has the most beautiful hands I have

ever seen.

Excerpted from Sorrow and Bliss. Copyright © 2021 by Meg Mason. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an

imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

We hope you enjoy the book recommended here. Our goal is to suggest only things we love and think you might, as

well. We also like transparency, so, full disclosure: We may collect a share of sales or other compensation if you

purchase through the external links on this page.

[ad_2]

Source link