[ad_1]

In partnership with our friends at Comvita

You either have a prized pot of manuka honey sitting in your pantry, or you’re reading this wondering how any 8.8-ounce jar of honey has the right to be fifty-seven dollars.

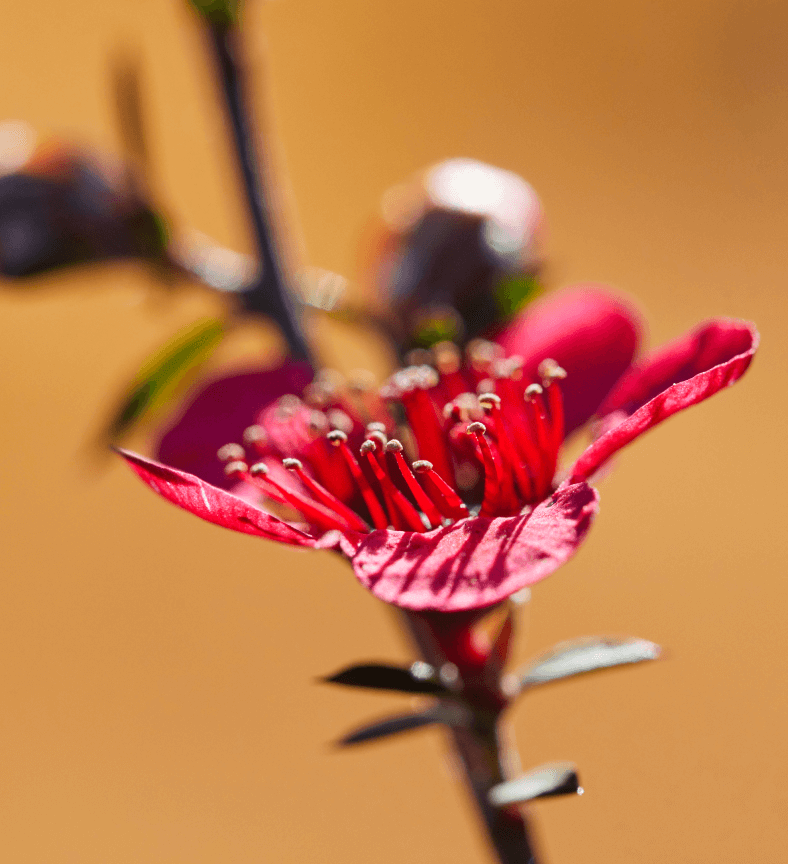

It all starts with the manuka tree, which is a plant species indigenous to New Zealand. Manuka honey comes from the nectar of those flowering manuka trees—and compounds in manuka honey, in particular methylglyoxal (MGO), have been shown in cell studies to possess antimicrobial and antibacterial activity.

Why collect honey and not just the nectar? The answer is twofold. “First of all, collecting manuka nectar is very labor-intensive,” says Jackie Evans, PhD. Evans is the chief science officer at Comvita, a company that has been producing manuka honey in New Zealand for more than four decades. “When we go out and test the nectar of our trees, it can take one person ten to fifteen minutes to collect around ten microliters of nectar using a pipette,” she says. They’ve done the math: It would take a hundred people working from dawn to dusk two full months to collect enough nectar to fill one 8.8-ounce jar.

But the primary reason we covet the honey and not the nectar comes down to the marvel of bees doing what bees do. “The way the bees make honey, it’s not just a matter of transferring nectar from the flower into a honeycomb,” Evans says. “They actually take the nectar into their separate honey stomach, and they mix it with enzymes from their mouth as part of the process of turning it into honey.”

There’s a short flowering period—about two to six weeks every year—which is the only window of opportunity for the bees to do their thing. And, Evans notes, bees do not like to fly when it’s wet or cold, so good weather during this period is key. Any sign of rain and wind and they’ll stay in their homes and consume the honey they’ve already collected. (We would, too.) Beekeepers at Comvita work with the bees year-round to keep them healthy and to help them grow their brood.

When you’re shopping for manuka honey, you want to make sure it contains the compounds you’d expect it to. That’s where the Unique Manuka Factor (UMF) comes into play: It’s an independent certification process that ensures the presence of those key compounds: leptosperin, dihydroxyacetone (DHA), and MGO. (DHA converts to MGO.) UMF ratings—5+, 10+, 15+, 20+—are assigned based on the levels of MGO and leptosperin detected in each batch of honey.

Part of the reason the levels of those compounds vary ties back to the nature of the nectar: Bees can fly miles in any direction, and manuka flowers are much less prolific than say, clover flowers. Given the choice, bees may go for the non-manuka varieties—again, relatable behavior—and that results in a less pure honey. To get a true monofloral manuka honey, hives are placed near a high volume of manuka blossoms at the right time with the right climate conditions.

Another reason for variation is the manuka trees themselves. Trees that have nectar with high levels of DHA result in honey with higher levels of DHA and MGO.

You can also taste the difference. “As you go up the grades of honey, you’ll notice a difference in the flavor because of the amounts of these compounds,” Evans says. “Manuka honey is quite a dark honey, and generally that’s because some of the compounds do have a color to them, like flavonoids and phenolic compounds—the same compounds you find in dark vegetables.”

Evans recommends looking for the lower UMF grades if you want to trade up from a normal honey and get some of the benefits. “Your 5+ and your 10+ jars you’d use in smoothies or on your cereal as kind of everyday use,” she says. “The 15+ and then the 20+ I reserve for more targeted reasons.” She recommends putting that honey in a warm drink or taking it straight off the spoon. You can also apply it directly to your skin, and it makes a pretty incredible single-ingredient face mask.

Something we appreciate about Comvita in particular is its commitment to treading lightly on the earth that allows for all that magic to exist in a single jar. The company has pledged to be carbon-positive by 2030 and to have 100 percent compostable or recyclable packaging by 2025. A third of its sites are powered by renewable solar energy. And it’s planted and managed 6.4 million trees in New Zealand since 2016: Planting native trees helps restore soil-eroded land, which helps clean waterways and supports aquatic biodiversity and local habitats.

This article is for informational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice. To the extent that this article features the advice of physicians or medical practitioners, the views expressed are the views of the cited expert and do not necessarily represent the views of goop.

[ad_2]

Source link