[ad_1]

On paper, Americans who have fallen behind on the rent are protected from eviction until July under a federal order. But at least three courts have recently issued rulings effectively nixing the eviction protection, leaving renters around the U.S. a step closer to homelessness.

Nowhere is this more evident than Memphis, Tennessee, according to legal experts and housing advocates. Local housing laws favor landlords over tenants, and while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s moratorium and local restrictions temporarily slowed evictions, the federal court in the state’s Western district ruled last month that the federal government likely exceeded its authority when it moved to halt evictions.

Although the government plans to appeal the case, eviction filings in Shelby County, which contains Memphis, have risen rapidly. Housing advocates also worry the city is a bellwether of what could happen elsewhere around the U.S. as the federal moratorium and many local eviction bans expire.

“What we are seeing is exactly what we expected when the CDC’s order would end. People who qualified for those protections, who had asserted those protections, were now being evicted,” said Katy Ramsey Mason, an assistant professor at the University of Memphis’ School of Law.

Ramsey Mason runs the school’s legal clinic, which typically handles health care issues but which pivoted during the pandemic to also handle eviction cases.

“A lot of people are contacting us with the impression this moratorium will keep them housed,” said Jeremiah Smith, an organizer with the Memphis Tenants Union. “We’ve definitely seen an uptick in tenants who are telling us, ‘Hey, I’m being called into court.'”

Brief reprieve

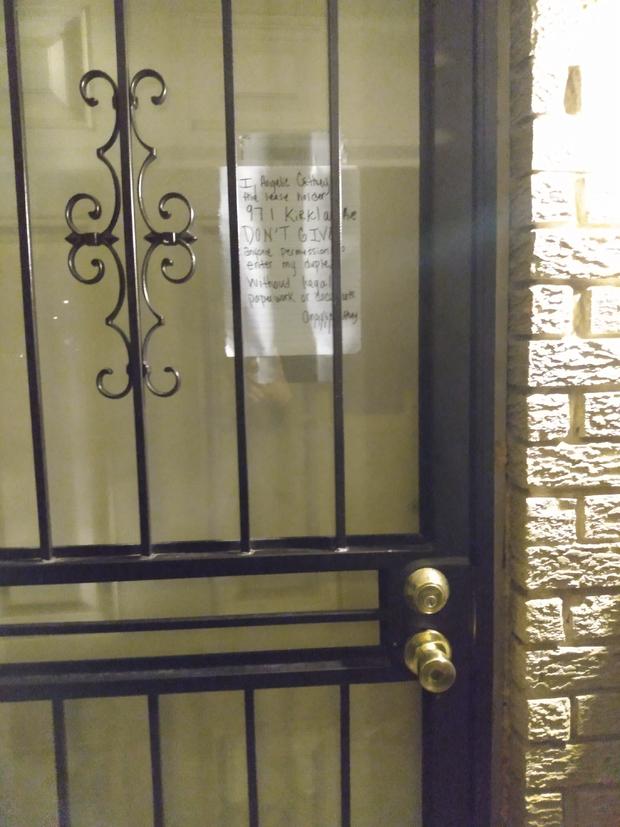

Angelic Cathey, who rents a two-bedroom in South Memphis, had her first eviction hearing Friday, six months after her landlord filed eviction papers. The 29-year-old left her restaurant job last year after repeated closings and re-openings during the pandemic disrupted her earnings. She now earns $7.25 an hour working full-time at McDonald’s.

Cathey lives with her fiance, who lost his job at a country club last year when the pandemic took hold and who now does odd jobs when he can find them. Also living with her are her three sons, ages 10, 8 and 5.

Her duplex was sold in June, and while Cathey initially got along with her new landlord, she soon stopped paying her $400 monthly rent because the landlord wasn’t making required repairs, Cathey told CBS MoneyWatch. Her home was often without heat and didn’t have a working oven, Cathey said. Instead of rent, she used her wages and federal stimulus money to pay for utilities so her sons could attend school remotely, and on taking her kids out to eat, saying she didn’t have a working oven or stove.

Angelic Cathey

“It’s a blessing that me and my kids wake up every day to be alive,” she said. “My light bill is the stimulus check — $1,400 ain’t nothing when you have three kids, when you’re already behind.”

Cathey’s landlord, Destanie Palmer, maintains that she made all the needed repairs. Palmer, who at 36 is a first-time landlord, bought the duplex intending to use it as an income property, she told CBS MoneyWatch. In January, Palmer tried unsuccessfully to evict her tenant using private security guards, but the attempt failed after community activists and members of Memphis Tenants Union camped out on Cathey’s lawn. The two women have not been in direct contact since.

Palmer told CBS MoneyWatch that she believed the CDC’s eviction moratorium expired at the end of December and that she did not know she needed a judge’s order to evict a tenant.

Angelic Cathey

Cathey’s case is hardly unique. The county where she lives had a backlog of about 10,000 eviction cases at the start of the year, according to a January news report.

“There are a lot of cases that have been waiting to get acted upon … . What we’re seeing right now is some of that backlog,” said Cindi Ettingoff, CEO of Memphis Area Legal Services, adding that demand for the group’s services has surged since the winter.

“A band-aid at best”

Memphis has long been a tough city for renters. In 2019, its eviction rate was more than double the national average, according to Princeton University’s Eviction Lab. That year the county saw 26,000 eviction cases filed. Tenants prevailed in less than 2% of those cases, according to a recent analysis by Legal Services Corporation. As in many American cities, parents are more likely to face eviction than nonparents, and Black renters more so than White renters.

The historic economic crash caused by the pandemic has multiplied the financial stress.

“It’s been a bad place to rent. The moratorium has been a band-aid at best, patched a hole in the dam,” said Austin Harrison, a consultant with Innovate Memphis, a nonprofit tracking eviction activity and other property data.

Eviction filings slowed over the winter while Tennessee courts were closed because of coronavirus, but cases have jumped since then. Filings in March rose to half their pre-pandemic level, Harrison said. In the first two weeks of April that followed the federal court’s decision rescinding the CDC moratorium, more eviction cases were filed than in the entire month of February.

Other courts nationwide also have struck down the CDC order, but the decision in Tennessee’s western district is the farthest-reaching, according to housing advocates. The Eastern District of Texas in February sided with landlords in agreeing the CDC did not have the power to regulate landlord-tenant relationships. The Northern District of Ohio also sided with landlords in March in ruling that the CDC overstepped its authority with the eviction ban. However, both decisions only apply to the parties in those cases, and don’t set a binding precedent.

The Tennessee decision covers about 1.5 million people in the state’s western half. A federal appeals court denied the federal government’s request for a stay while the government appeals. So although the decision could eventually be overturned, renters now face a heightened threat of eviction, while other courts could follow Tennessee’s example.

“We are already a city that struggles with a lot of social and racial justice and economic issues. We already have a 30% overall poverty rate,” said Ramsey Mason, the housing lawyer. “For a city like Memphis to be the only major city in the country where this order is not in effect — we are dealing with a potential homelessness crisis that will affect, by and large, poor people of color, and their children.”

Not enough time

In normal times, a renter in Memphis could have as little as two weeks between receiving an eviction notice and being ejected. The CDC’s order, by preventing physical removal of tenants, gave tenants more time to come to make arrangements with their landlords or to seek rental assistance.

“It was helping us manage that more effectively because we had more time. It wasn’t like, we have to help this person today or they’ll get evicted tomorrow,” said Mason.

One of Ramsey’s clients is a mother who lost her job during the pandemic and was evicted in the first week of April. The woman is now living in a hotel with her kids and applying for unemployment benefits while she searches for a place to live, Ramsey said.

“I talk to people every day who’ve lost their jobs in the service industry, home health care, child care, who are still struggling to get back on their feet — a lot of folks who in the last few months have been able to start working again but aren’t in a position to pay off arrears,” she said.

Cathey said she applied for half a dozen grants and fundraisers before being approved for rental assistance through a county program. However, Palmer, her landlord, hasn’t accepted the payments, Cathey said.

Palmer said the program has not contacted her to offer payment. A judge has given the women until April 28 to reach an agreement.

“If she has her money, I would take it,” Palmer told CBS MoneyWatch. “I never wanted to evict her in the first place. But I want my money. I don’t want to wonder every month if she’s going to pay or not.”

National trends

Housing advocates worry that a backlog of eviction cases, coupled with what appears to be a recovering national economy, will make local judges more willing to rule against tenants.

“With warmer weather, COVID vaccines are available — you’ve eliminated part of that argument, that you’ll have to live in crowded housing where COVID-19 will be spread,” said Ettingoff of Memphis Area Legal Services.

Cathey has been spending her time preparing for a seemingly inevitable move. She’s resisted going to local shelters where she fears she would be separated from her sons, and is considering staying in the basement of her local church as a last resort. Just before her court hearing, Cathey got news that she was approved for a housing voucher she had applied for eight years prior. She has only until June to find an apartment that will accept the voucher, as well as overlook the eviction case on her record, before it is rescinded.

“I’m still trying to find a way to get it done,” she said. “I’m putting my pride to the side.”

[ad_2]

Source link