[ad_1]

Definition | Do they work? | BCAAs vs whey | BCAAs vs. EAAs | BCAAs vs food | Bottom line

“Get ripped with BCAAs,” says the company that sells them.

“I took BCAAs and had way more gains,” says guy at the gym.

“Taking BCAAs twice a day helps recovery,” says fit human on Twitter.

With all the talk, it’s enough to make any muscle-conscious person wonder: Should I be taking a branched chain amino acid (BCAA) supplement!?

Unless, however, you’re a molecular biologist with a specialty in muscle development. (That’s me.)

Or you’re someone like Stuart Phillips, PhD, one of the world’s top protein researchers. He’s the principal investigator at McMaster University’s protein metabolism lab—one of the most prolific protein metabolism labs in history, publishing more than 250 research papers that have been cited more than 32,000 times.

When making BCAA claims, people often cite research from Dr. Phillips’ lab.

Yet Dr. Phillips doesn’t recommend BCAA supplementation—for anything.

So if THE expert on BCAAs doesn’t recommend them, why do so many people swear by the supplement?

And what other, less expensive options might work just as well or better?

Let’s find out.

What are branched chain amino acids (BCAAs)?

Before we get into what BCAAs are, let’s talk about amino acids in general.

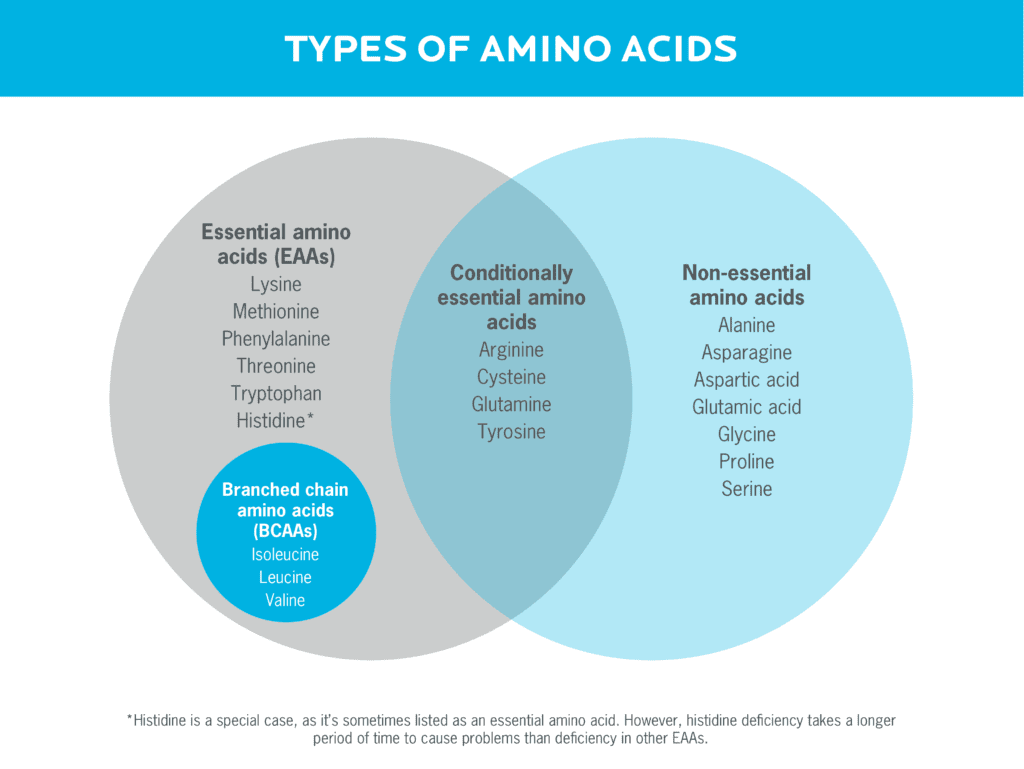

Amino acids are the building blocks for protein. There are 20 different amino acids, divided into three categories.

Amino acids can be divided into three categories: essential amino acids, conditionally essential amino acids, and non-essential amino acids.

Your body can make some amino acids—these are called “non-essential”—but they have to get others from food. These are called essential amino acids. Conditionally essential amino acids can be made by the body some of the time, but not under times of stress—like after a tough workout, or when you’re sick.

Branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) are a subgroup of three essential amino acids (EAAs):

- Isoleucine

- Leucine

- Valine

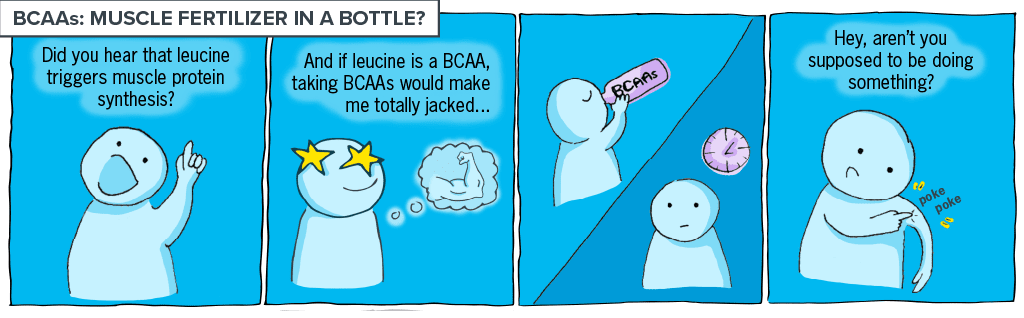

Of the three BCAAs, leucine is the most researched, and appears to offer the biggest physiological benefit. It stimulates muscle protein synthesis, which is when muscle cells assemble amino acids into proteins. This process is key if you want to build muscle strength and size.

Around the turn of the millenium, Dr. Phillips was one of several researchers who helped figure out that leucine was the star of the muscle-building show, because of its stimulating effect on protein synthesis.1-4

When his and other studies were published, people in the muscle-building universe got excited.

Their thinking went like this:

But hold up, muscle-building universe—don’t get too excited…

Do BCAAs work?

Probably not—for many reasons. Here we go into just three of them.

Reason #1: Leucine can’t build muscle without other amino acids.

Here’s an analogy: Think of muscle as a brick wall.

Granted, this will be an unusual wall that someone builds and destroys over and over again—but visualize a wall nonetheless.

When it comes to building that wall, leucine is the most important brick. The wall doesn’t get built without it.

But leucine can’t finish the job all by itself. You also need histidine bricks, lysine bricks, methionine bricks, and many other amino acid bricks.

If you only have a pile of leucine bricks? No wall.

If you have a pile of leucine, isoleucine, and valine (the BCAAs)? Still no wall.

You need bricks from all 20 amino acids.

Bottom line: To build muscle, you need all the amino acids, not just leucine.

Reason #2: Leucine doesn’t work like lighter fluid.

People wrongly assume: The more leucine (from BCAAs, EAAs, or whole protein) you take, the more protein synthesis you get. And more protein synthesis means bigger muscles.

Light those muscles up, baby!

Except the mechanism is more like a dimmer switch, Dr. Phillips explains.

Leucine will turn up the protein synthesis switch—but not indefinitely.

It doesn’t continually make the lights brighter and brighter until it’s just you and the sun hanging at the gym, getting infinitely more swole.

Here’s how it actually works:

About 0.5 grams of leucine turns on the lights, initiating muscle protein synthesis. You’ll find that much in an egg—or any other food that contains at least at least 5 grams of complete protein.4

You’ll max your wattage somewhere around 2-3 grams of leucine, though the exact amount will vary based on your sex, body size, and age.4-6 You’ll find roughly that much in a meal that contains ~20-30 grams of complete protein, found in:

- 3-4 ounces of meat

- 3-5 eggs

- 1-2 cups of Greek yogurt or cottage cheese

Bottom line: Leucine turns up muscle protein synthesis, but only to a point.

Reason #3: BCAAs don’t go straight from your mouth to your muscles.

They first have to make their way through your intestines, and into the bloodstream. (And many don’t.)

Amino acids compete with one another to enter little doorways (called transporters) to get into the bloodstream. And they can only use the doors specific to their amino acid type. If you flood your GI tract with single amino acids from a BCAA supplement, the doors reserved for single amino acids will get backed-up. Instead of your bloodstream, they end up in your toilet.

And the ones that do get into the bloodstream? They still have to find their way into your muscles. (Again, many don’t.)

That’s because leucine can only get into a muscle cell if another amino acid (called glutamine) happens to be leaving the muscle at the same time. So if you have a ton of leucine—and not enough glutamine—leucine either can’t get into the muscle cell at all or it does so very slowly.

Bottom line: Leucine needs glutamine to effectively get into muscle cells.

What’s best: BCAAs vs. whey protein vs. EAAs vs. food

Let’s start with the truth, straight from Dr. Phillips’s email to me when I told him about this story: “BCAAs are a waste of money… kind of sums up my position.”

Here’s why:

If you want to supplement, spend your money on Essential Amino Acids (EAAs). You need all of the EAAs to build muscle, not just leucine.

But, for most people, even EAA supplements aren’t necessary. And they may not be superior to… food. Truth is, we don’t fully understand the complexity of the interactions between amino acids and other nutrients in the body. It’s likely that the ratio of amino acids is more important than the absolute amount of one amino acid or nutrient.

Luckily, we evolved eating whole foods that likely (naturally) have the ratios we need to function well.

In other words, the best “supplement” may be the one that you slice with a knife, spear with a fork, and mash between your molars before swallowing.

The #1 source of amino acids

Yogurt, chicken, rice combined with beans, and other protein-rich foods contain all of the amino acids that most people need for muscle development. And, they cost less than supplements.

The “just eat real food” approach will work for you if:

✓ You’re ready, willing, and able to eat protein-rich foods throughout the day. Data shows muscle growth is maximized by a daily protein intake of 1.6-2.2 grams/kilograms (g/kg) body weight. Try to distribute protein throughout the day, with an intake of about 0.4-0.6 g/kg per meal (assuming you eat about 3-4 meals per day). For specific protein recommendations based on your sex, age, and body size, use our macros calculator.

✓ You’re under age 65. It takes less protein to stimulate protein synthesis when you’re younger, making it pretty easy to get all you need from food.

The #2 source of amino acids

Let’s say consuming 1-2 protein portions per meal sounds unlikely. In that case:

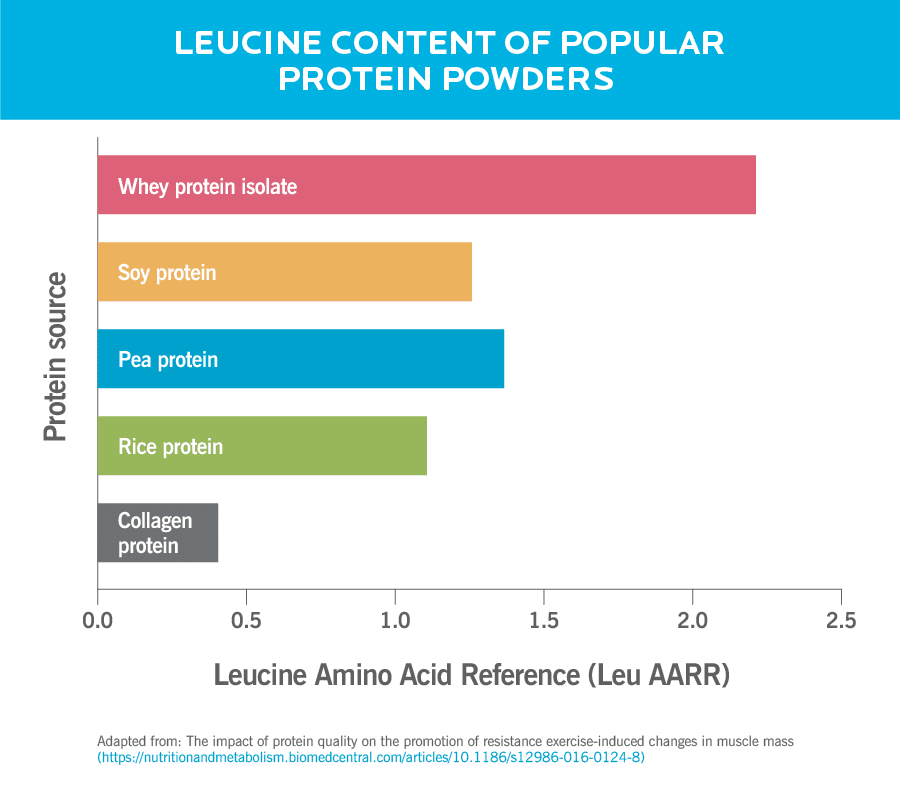

Whey protein is your next best option.

As the chart below shows, when compared to other protein powders, whey contains the most leucine and EAAs per scoop.8,4

(Read “How to choose the best protein powder” to fully understand how these options stack up.)

Whey protein is a great option for:

✓ People who don’t really like protein-rich foods. If you’re not sure if this describes you, write down what you ate in the last few days. Then check how many palm-sized portions of protein you tend to eat per meal. If you’re not getting 1-2 palms of protein per meal, whey might save the day.

✓ You’re trying to lose weight—and you’re hungry. You might want to periodically mix up a simple whey protein shake to stop the growlies—for relatively few calories.

✓ You’re 65 or older. Protein needs go up as we age. At the same time, some older people either feel less hungry or have trouble chewing and digesting certain protein foods. All of this makes it more difficult to get enough protein from food alone.

✓ You’re trying to gain muscle while losing fat. Usually, when people gain lean mass (which includes muscle), they also gain a bit of fat along with it. Conversely, when they lose fat, they also lose some muscle.

(No one ever said life was fair.)

But you might be able to minimize your muscle loss if you eat more protein while cutting calories, finds research.9

Compared to a steak, whey protein is relatively low calorie, making it easier to boost your protein consumption without also boosting your calorie intake.

So, if you’re older, or wanting to increase protein consumption in an easy, calorie-minimal way, whey’s a good protein source to add to the roster.

The #3 source of amino acids

For the vast majority of people, either whole foods or whey protein offers everything they need.

But EAAs might be a good option if:

✓ You’re an athlete who’s trying to shed fat for a competition. Whey protein isn’t calorie dense. But in those rare situations where every single calorie counts, it might make sense for you to use EAAs instead, which provide your muscles with the essential building blocks, at very few calories.

✓ You can’t stomach protein powders. Some people have trouble digesting whey and other protein powders. Or they could be allergic to dairy. In those cases, EAAs might be a better option.

✓ You don’t mind the flavor of EAAs. Fair warning: they’re bitter.

When should you consume protein? Before, during, or after exercise?

Maybe you’ve heard that you should consume protein right after a workout—in order to take advantage of something called “the anabolic window.”

But this is a misinterpretation of the research.

Yes, exercise does make muscles more sensitive to protein synthesis. In other words, the anabolic window is real. But that window remains wide open for a long time. Eating meals within two to four hours of your workouts puts you well within it.

And most people, unless they’re fasting, are going to eat within four hours of a workout.

Bottom line: BCAAs (usually) aren’t worth it.

Even after you read this, maybe you still want to try BCAAs. Or you have a client who’s itching to experiment with them.

That’s okay!

Because the best way to find out whether anything does or doesn’t work for you is this: run an experiment.

How to experiment with BCAAs if you really, really want to try them.

Before you start, decide on a few metrics to track. You could measure your:

- Appetite, on a 1 to 10 scale before and after meals.

- Weight or girth measurements

- Power / strength output at the the gym

Jot down your baseline(s).

Then go ahead and start taking BCAAs.

After a few weeks, check back in. How do you feel? What progress are you making? Is the supplement working? Have you seen a difference?

If yes, keep doing what’s working.

If no, that’s helpful information that could save you some money.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, preferences, and circumstances—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

[ad_2]

Source link