[ad_1]

When Singapore’s new cabinet meets in mid-May, critics fear a new scenario will be in place, one that reverses a process that Lee Kuan Yew, the country’s modern patriarch, initiated in 1990. That was to prepare the island nation for a future without the Lee family in charge.

Lee Hsien Loong, the 69-year-old prime minister and Kuan Yew’s son, in mid-April presided over the cashiering of the lackluster premier-in waiting, Heng Swee Keat. Last week, as the new cabinet names were announced, it had become clear that Heng’s successor would be on what was being called a “long runway.” How long that runway will be is anybody’s guess, and while Lawrence Wong, 48, has been moved up from education minister to finance minister, it is uncertain, with two other strong candidates, if Wong will eventually be anointed.

There is growing danger that the ruling People’s Action Party is damaging the perception of its competence, one of the foundations on which its reputation has rested. Heng Swee Keat was supposedly picked by his party peers and groomed for power because he was first among equals. But reports arose that he was widely disliked in his district – indeed, he did badly in last year’s polls although he survived – and that he was abrasive and difficult to get along with, which contributed to his sacking.

Anyhow, it is widely believed in Singapore that Lee Hsien Loong will remain in power until the next national election, not due before August of 2025. He had earlier pledged to move on, as his father had, to make way for a new generation, but announced he would stay on to take on the Covid-19 coronavirus. The country has done a creditable job, with 61,000 cases and only 34 deaths.

“It is clear that Lee is holding onto power, but it is not clear why, or what he is waiting for,” said Michael D. Barr, an associate professor and Singapore expert at Flinders University in Adelaide. “This business of him holding on to give the fourth-generation leaders time to sort out the succession mess is nonsense. If he wanted to give the next PM the chance to step up and have plenty of time to make his mark and assert his authority before the next general election, he would simply announce that he is stepping down in a month, or a week, and leave them to sort it out. And they would.”

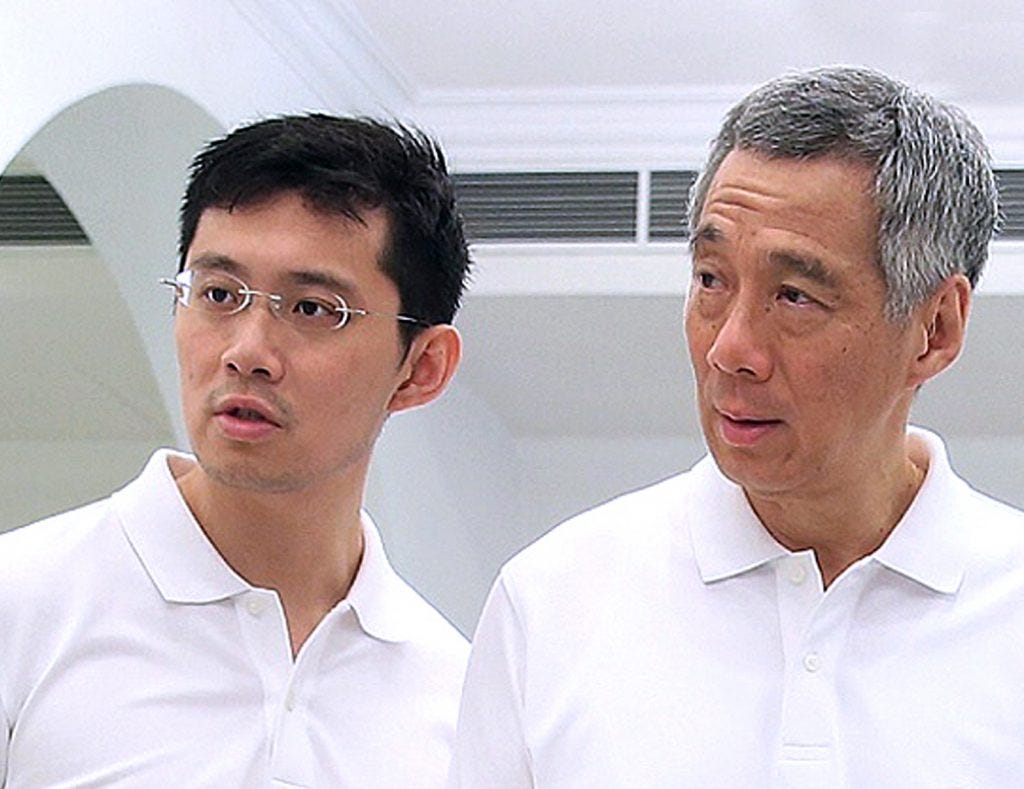

By deciding to continue in power, Hsien Loong is contributing to suspicions that he intends to perpetuate a Lee dynasty by ultimately working out a stratagem to bring his son, Li Hongyi (above, left, with his father), currently a director of a government technology firm, into power although the son has said he is not interested in a political career.

This is an idea that in the past has been met with stiff resistance and resort to the Singapore – but not international – courts by the family. In 2010, the now-defunct International Herald Tribune apologized to Hsien Loong, Kuan Yew, and former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong and paid a hefty fine for an article on dynastic politics in Asia despite the fact that nowhere did it say or imply that nepotism played a role in the Lee family’s – or any other family’s – political prominence in the region. In that way, the case is reminiscent of another in which the Financial Times apologized for a September 2007 article in which there appeared to be no libel. The article merely listed the names of Lee family members in high positions in the island nation.

“The smart money said that he wanted a stopgap to give Li Hongyi the chance to enter politics and earn his spurs,” Barr said, “but it wasn’t clear who was the main driver of this – Li Hongyi or his mother, Ho Ching.”

Another Lee in power might not play well with an electorate that seemingly is losing its taste for a dynasty. Lee Kuan Yew voluntarily stepped down from 31 years in power in 1990 at age 67 despite being one of the most powerful leaders in Asia, proclaiming he was doing so to clear the way for new leadership. He was succeeded by Goh Chok Tong as he took a seat in the cabinet as senior minister and later as “minister mentor.” It was clear at the time that Lee Hsien Loong was being groomed to take power, which he did in 2004, and has ruled for 17 years.

A longtime top civil servant disagreed with that scenario. “There are no rumblings at all at the prospect of Hsien Loong now staying longer,” he said. “In fact, most people welcome the prospect as they feel the younger 4G aspirants can only benefit from the extra time (or is it a longer runway?) afforded them.”

Hsien Loong, he said, “is left with an unexpected burden. His advantage is that the Singaporean voting public is intrinsically practical and is absolutely more interested in bread and butter and quality of life issues than the PAP rising star. So long as people can put food on the table and have a decent and safe life, they are not going to be overly critical. They recognize that these are different and difficult times.”

Anyone who takes over, be it Lawrence Wong or ministers Ong Ye Kung and Chan Chun Sing, both of whom have been mentioned in the past, is likely to be regarded as beholden to the Lee family, and “that is exactly what Lee doesn’t want,” Barr said. “He wants to be able to exercise power. He thought he could do it through Heng, since Heng is so obviously a creature of the Lee family, and clearly no one was ever going to marvel at how good a job he was doing. But that plan is out the window because Heng was much too obviously below par, an embarrassment.”

The general disenchantment on the part of the general public, which already manifested itself in the general election last August when voters handed the PAP its worst showing since 2011. The PAP won only 61 percent of the vote but nonetheless took 83 of the 93 seats due to fiendish gerrymandering, the first-past-the-post parliamentary system and group constituencies, which were established in the 1980s by Lee Kuan Yew. The GRCs, as they are known, group some districts together, supposedly so that weaker minority race candidates could stand with stronger Chinese candidates, preserving Singapore’s racial balance. But actually, it was designed to thwart the country’s tiny, fragmented political parties, which couldn’t at that time field enough candidates to fill out the GRCs. The opposition Workers’ Party finally won its first GRC in 2011, 23 years after Kuan Yew invented and implemented the stratagem.

In Singapore’s general election in 2020, the Workers’ Party won 10 constituencies, its highest number ever. Hsien Loong officially designated leader Pritam Singh as opposition leader, effectively making the Workers’ Party an alternative government.

Another indicator of growing disenchantment with the PAP and the Lee family was delivered in April, when an opposition political figure, Leong Sze Hian, the latest victim of Lee family serial defamation suits, became the first individual to raise enough public money to fully pay off S$133,000 (US$99,000) ordered by the high court within days after he was convicted of sharing an article uploaded onto Facebook deemed to have libeled Hsien Loong.

Leong was followed in short order by Roy Ngerng, who was convicted of libeling Lee in 2015 and fined S$100,000 and S$50,000 in costs. Ngerng, now in voluntary exile in Taiwan, organized a crowdfunding effort to pay off the fine and costs but the effort sputtered until Leong’s effort was publicized. Ngerng now has raised the full amount and paid it off, an indication that irritation over incessant libel suits and the use of crowdfunding to pay them off appears to be weakening the power of legal tactics used for decades by Singapore leaders in local courts.

Then there is the bitter feud between Lee and his younger brother and sister in a tangential family squabble over the disposition of their father’s home which has shocked a public long used to a tightly-buttoned ruling family and raised concerns about their perceived invincibility.

In August 2017, the Attorney-General prosecuted Li Shengwu, Lee Hsien Yang’s eldest son for scandalizing the judiciary over a private Facebook post. In January 2019, the tangle of family loyalties was strained further when the country’s Attorney-General, Lee Hsien Loong’s former personal lawyer, initiated legal malpractice proceedings against Lee Suet Fern, Lee Hsien Yang’s lawyer wife, who had assisted the family in the making arrangements for the witnessing of the final will.

In an email exchange with Asia Sentinel, Hsien Yang commented on called the current cabinet reshuffle and sacking of Heng “In my view, Lee Hsien Loong is consolidating his power. He is not about to go anywhere soon.”

“Lee’s assumption that staying at the helm indefinitely is the best reassurance for Singaporeans is problematic,” said Garry Rodan, also an Australian academician with wide experience in Singapore politics. “It is an indictment of the PAP’s much-trumpeted claims about precision political transitions that this first attempt to handover has been fumbled. The longer Lee Hsien Loong remains prime minister, the more Singaporeans will be reminded of this. It will also stoke suspicions that there is an undeclared preferred replacement not yet in a position to succeed the current prime minister.”

[ad_2]

Source link