[ad_1]

The front-page shockers began in early April and just kept coming: A young mayor from the San Francisco Bay’s wine country had been accused of sexually abusing and assaulting women. First there were four accusers. Then four more.

A former girlfriend accused Dominic Foppoli, the mayor of “friendly, family-oriented” Windsor, of sexually abusing her. Another woman said he forced himself on her during an alcohol-fueled hot tub party at his family’s winery. A town council colleague said she might have been drugged before she was sodomized following a community clambake.

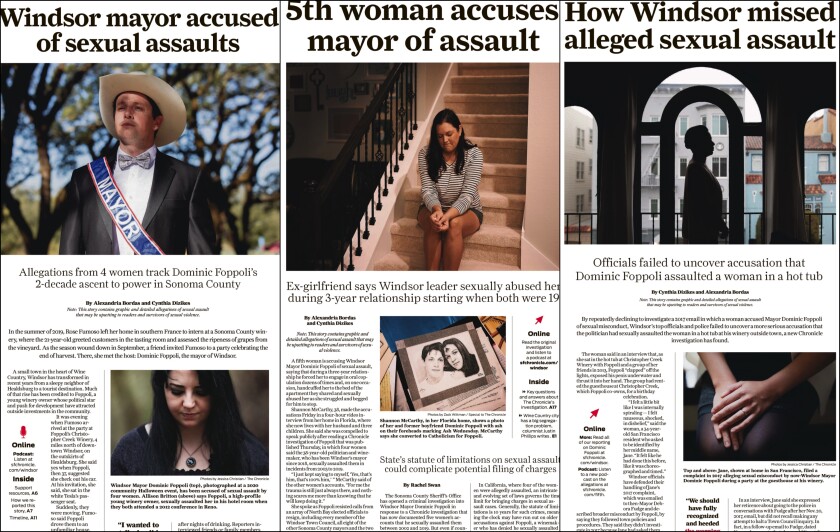

The headlines were stunning, but they came not from Sonoma County’s leading media outlet, the Press Democrat, but from its big-city rival, the San Francisco Chronicle. The allegations, which led Foppoli to resign his mayorship on May 21, have rocked the Pulitzer Prize-winning Press Democrat, after its top editor made the extraordinary admission that the newspaper had failed to pursue the story when a reporter brought forward the first accusations, more than two years ago.

Reporter Alexandria Bordas left the Press Democrat in 2019 and eventually took her information — including two women’s allegations that they had been sexually assaulted — to the Chronicle. The San Francisco paper soon teamed Bordas with Cynthia Dizikes, a veteran investigative reporter, and the two journalists landed their blockbuster. Then came a raft of damning follow-ups, a deluge of calls for Foppoli’s resignation and, at the Press Democrat, soul searching and recriminations about the story that got away.

Alexandria Bordas, who broke the Foppoli story for the San Francisco Chronicle, after leaving the rival Santa Rosa paper.

(San Francisco Chronicle)

“Editors failed to follow through and pursue the story. We failed our loyal readers and Windsor voters and residents,” Press Democrat Editor Richard Green wrote in a statement to readers last month. “Even more important, our decision to not thoroughly investigate these women’s accounts about alleged incidents involving Foppoli may have caused more personal heartache, humiliation and physical and emotional harm for other women. … There is no excuse for our failure to not push harder; to not dig deeper.”

In the weeks that followed that April 9 declaration, the Press Democrat placed its No. 2 editor, Ted Appel, on administrative leave. He soon resigned, though he and the paper have not commented on the reason for his departure. Another editor was demoted, and a third issued a mea culpa for his fraught relations with reporters, as the staff vented its dismay in a Zoom call.

Every media outlet misses important stories and has its share of in-house turmoil. But in a proud Santa Rosa newsroom that only three years ago won a Pulitzer for its coverage of the 2017 wine country fires, the sense of outrage remains high.

“Our failure to follow through on the story was egregious and inexcusable and was made over and over and over again,” said one reporter, who asked not to be named, to preserve relationships with colleagues. “Even as this guy ran [last November] in his first election for mayor, there was no attempt to follow up.”

Dominic Foppoli, owner of Christopher Creek Winery, resigned as mayor of Windsor amid sexual assault allegations.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Hundreds of readers also complained, many speculating that Foppoli’s political and business connections, as the son of longtime winemakers, might have made him immune from scrutiny. Heightening those questions, for some, was the fact that the Press Democrat has been owned since 2012 by a group of influential political and business figures. Said one reader on Facebook: “There is much work to do to regain trust.”

The outlines of the original story were sensational, particularly given the identity of the accused. Foppoli had cultivated a persona as the “prince” of a family that claims winemaking heritage dating back 600 years, to its roots in northern Italy. A young Republican in a county dominated by Democrats, he first ran for state Assembly (unsuccessfully) when he was still a student at Dominican College of California, in San Rafael. He hosted promotional videos with celebrity chef Guy Fieri. He competed on TV to be named California’s most eligible bachelor. Said one acquaintance: “He was the fun, connected guy who was going places.”

Foppoli, 39, spent weeks insisting he had done nothing wrong and refusing to step down. He finally resigned as the Chronicle prepared to report on allegations from a ninth alleged victim. Farrah Abraham, a reality television star, said she had been sexually battered. While authorities in Palm Beach, Fla., pursue that case, the state attorney general’s office is handling the criminal investigation in California.

“I did not engage in any non-consensual sexual acts with any woman,” Foppoli said in his three-paragraph resignation letter. He said he was stepping down to prevent “undue national attention” that could hurt Windsor, “because of lawful, but poor choices, I have made in the recent past.”

The San Francisco Chronicle published repeated front-page scoops on the Foppoli scandal.

The furor shows no sign of abating, in part because of the alleged failure of local institutions to pursue complaints about Foppoli. One Chronicle story offered evidence that Windsor town officials failed to follow up four years ago, after one alleged victim claimed the ambitious politician had sexually abused her during a 2013 hot tub party at a guesthouse run by Foppoli’s Christopher Creek Winery. (City officials insisted they had followed the proper protocols.)

Bordas, 31, has declined to discuss the story, or what went wrong when she brought it to her editors at the Santa Rosa paper.

The general outline of the journalistic failure appears clear: Bordas came to the Press Democrat in late 2018, after attending the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and working a year at a North Carolina newspaper. Among her early assignments was coverage of Windsor, a town of 28,000 that incorporated only in 1992 but has grown more rapidly than its older and better-known neighbors, like Sonoma and Healdsburg.

The community takes particular pride in its Town Green, the scene of summer concerts and kids’ movies, where families loll on the grass with picnic baskets and bottles of wine. Windsor’s most flamboyant figure was the homegrown Foppoli, who in 2014 became the town’s youngest council member, at 32. He quickly developed a reputation as pro-development and always ready to network with colleagues and friends. He often traveled the Sonoma Valley with a case of the family’s wine in the back of his white Tesla.

Dominic Foppoli, owner of Christopher Creek Winery and the former mayor of Windsor, surveys his Russian River Valley operation in the wake of the Kincade fire in 2019.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Sometime in early 2019, a Press Democrat assignment editor told Bordas about rumors that Foppoli had engaged in “unsavory” behavior, another editor recalled. The reporter began to dig in and soon came back to editors with reports from two women who claimed they had been sexually assaulted by the mayor.

But after more than one conversation, editors told Bordas to focus on other stories. The reason why remains murky. Current and former Press Democrat staffers attribute it, in part, to a “feed the beast” culture common in many newsrooms.

American newspapers have been in crisis for at least two decades, as advertising revenue has fled to other media, particularly internet giants like Facebook and Google. More than half of U.S. newsroom jobs were eliminated between 2008 and 2019, according to the Pew Research Center. Most newspapers struggle to stay on top of daily basics that readers demand — such as government coverage, crime reports and high school game accounts — while also pursuing more ambitious stories, like the Foppoli investigation, fraught with the potential for costly miscues and litigation.

The Press Democrat has seen its union-represented news staff decline from 96 employees in 2005 to 39 today, according to the Pacific Media Workers Guild.

“How do you find the time to allow a reporter to spend even one day a week not producing copy to feed the beast?” said another former staffer, who asked not to be named. “The beast has gotten bigger and bigger,” he said, “as the staff feeding it continues to get smaller.”

But several current and former Press Democrat staffers said the problem went deeper. They complained of a top-down administration that dictated stories and sometimes didn’t listen to reporters, especially younger ones.

Editor Green, 55, took command of the Press Democrat just six weeks before the Foppoli news broke in the Chronicle, unaware that the paper had earlier passed on the story. The editor would subsequently learn that Bordas had uncovered the accusations as sexual misconduct allegations swept the nation.

“It was right in the middle of ‘Me Too’ when this happened,” said Green. “We didn’t provide the right support system to let her pursue a story that turned out to be a pretty damn big one.”

And an unusual lapse.

The California Newspaper Publishers Assn. has repeatedly named the Press Democrat as the top newspaper of its size in the state. In 1999, it broke news about a Roman Catholic bishop admitting he had sex with a priest. In 2009, it revealed the financial struggles of Sonoma County’s largest real estate investor, Clem Carinalli. The Press Democrat’s biggest splash came in 2017, when fires swept the North Bay, killing more than 40 people and causing billions of dollars of damage.

Press Democrat reporters and photographers plunged into the danger, providing instant video and written reports, constant social media updates and, finally, probing narratives about the genesis of the calamity. The Pulitzer judges honored the coverage as “lucid and tenacious.”

But the thrill of the Pulitzer victory had a “dark side,” according to one staffer, the peak experience encouraging some journalists to retire and others to find jobs elsewhere. “That creates more work and more pressure for the ones who remain,” said the reporter.

The organization of the newsroom and assignment of journalists to beats withered away, for reasons that aren’t clear, three staffers said. But many reporters were spread thin, with multiple duties. Bordas covered healthcare, in addition to Windsor.

“On a day-to-day basis we were proud of the work we were doing,” said another journalist. “But it felt like there was a ceiling, and we couldn’t be the shining light that most of us get in journalism to be.”

Critics both inside and outside the paper said they do not believe the Press Democrat backed away from the Foppoli story because of the politician’s connections. “It was an egregious mistake,” said one journalist, “but not something more than that.”

Catherine Barnett, the executive editor who retired at the end of 2020, after more than four decades at the paper, did not respond to a request for comment. Appel, the former managing editor, also did not answer phone calls. Several journalists said they were saddened at the departure of Appel, a mainstay at the Press Democrat for about three decades, who they said had supported tough coverage of local officials.

Current and former colleagues said they still weren’t clear on what Appel and other editors decided two years ago on the Foppoli story. Some wondered if editors were overly cautious because of Bordas’ relative inexperience, or because of a 2016 defamation lawsuit, though that case was eventually dismissed by an appellate court.

The Chronicle was not deterred. After the report about the original accusers, the San Francisco paper produced several more scoops, including about a Foppoli spokesman, prominent for lobbying the Trump administration, who used a misogynistic slur against Bordas.

The scandal took another dramatic turn when fellow Windsor Town Council member Esther Lemus said she had been sodomized and possibly drugged, after Foppoli and another man drove her home. Lemus, 48, went public with that information just hours after Foppoli issued a statement saying he was the victim and that Lemus had pressured him into a sexual encounter. Because she works as a prosecutor for the Sonoma County district attorney, that office recused itself and referred the allegations to the California attorney general.

Most of Sonoma County’s elected officials demanded the mayor’s resignation, as did many of his own constituents in a raucous video City Council meeting. But until last Friday, Foppoli insisted he would stay the course. He said he was the victim of a “witch hunt” by people intent on driving him from power.

Despite the humiliation of being beaten on a story in their own backyard, Bordas’ former colleagues privately cheered her for keeping the Foppoli story alive. “She had that energy and passion,” said one former co-worker. “We’re all very proud of what she did.”

After she left the Press Democrat in 2019, Bordas went to work for a nonprofit that teaches filmmaking to young people. She said in an online posting that she had “mostly transitioned out” of the news business. But those she covered would have been wise to heed her vow.

“There are many lingering stories that I did not have the time to tell while working in the media industry,” Bordas wrote. “So now I am able to chip away at them, one-by-one, to make sure they are told.”

[ad_2]

Source link